|

|

| (806 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Abiotic Reduction of Munitions Constituents== | + | ==PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment== |

| − | Munition compounds (MCs) often contain one or more nitro (-NO<sub>2</sub>) functional groups which makes them susceptible to abiotic reduction, i.e., transformation by accepting electrons from a chemical electron donor. In soil and groundwater, the most prevalent electron donors are natural organic carbon and iron minerals. Understanding the kinetics and mechanisms of abiotic reduction of MCs by carbon and iron constituents in soil is not only essential for evaluating the environmental fate of MCs but also key to developing cost-efficient remediation strategies. This article summarizes the recent advances in our understanding of MC reduction by carbon and iron based reductants.

| + | The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) which can destroy [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor">Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. [https://www.haleyaldrich.com/about-us/applied-research-program/eradifluor/ Comercial Website]</ref>) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633. |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| − | *[[Munitions Constituents]]

| |

| − | *[[Munitions Constituents - Alkaline Degradation]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributor(s):'''

| + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| − | *Dr. Jimmy Murillo-Gelvez | + | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] |

| − | *Paula Andrea Cárdenas-Hernández | + | *[[PFAS Sources]] |

| − | *Dr. Pei Chiu | + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] |

| | + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] |

| | + | *[[Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction]] |

| | | | |

| − | '''Key Resource(s):''' | + | '''Contributors:''' John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu |

| − | * Schwarzenbach, Gschwend, and Imboden, 2016. Environmental Organic Chemistry, 3rd ed.<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016">Schwarzenbach, R.P., Gschwend, P.M., and Imboden, D.M., 2016. Environmental Organic Chemistry, 3rd Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 1024 pages. ISBN: 978-1-118-76723-8</ref> | + | |

| | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| | + | *Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management<ref name="BentelEtAl2019">Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648] [[Media: BentelEtAl2019.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| | + | *Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies<ref>Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608] [[Media: LiuZEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| | + | *Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment<ref>Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961]</ref> |

| | + | *EradiFluor<sup>TM</sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> |

| | | | |

| | ==Introduction== | | ==Introduction== |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig1.PNG | thumb |left|300px|Figure 1. Common munitions compounds. TNT and RDX are legacy explosives. DNAN, NTO, and NQ are insensitive MCs (IMCs) widely used as replacement for legacy explosives.]]

| + | The hydrated electron (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988">Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555805 doi: 10.1063/1.555805]</ref>. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988"/>. |

| − | Legacy and insensitive MCs (Figure 1.) are susceptible to reductive transformation in soil and groundwater. Many redox-active constituents in the subsurface, especially those containing organic carbon, Fe(II), and sulfur can mediate MC reduction. Specific examples include Fe(II)-organic complexes<ref name="Naka2006">Naka, D., Kim, D., and Strathmann, T.J., 2006. Abiotic Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds by Aqueous Iron(II)−Catechol Complexes. Environmental Science and Technology 40(9), pp. 3006–3012. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es060044t DOI: 10.1021/es060044t]</ref><ref name="Naka2008">Naka, D., Kim, D., Carbonaro, R.F., and Strathmann, T.J., 2008. Abiotic reduction of nitroaromatic contaminants by iron(II) complexes with organothiol ligands. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 27(6), pp. 1257–1266. [https://doi.org/10.1897/07-505.1 DOI: 10.1897/07-505.1]</ref><ref name="Hartenbach2008">Hartenbach, A.E., Hofstetter, T.B., Aeschbacher, M., Sander, M., Kim, D., Strathmann, T.J., Arnold, W.A., Cramer, C.J., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2008. Variability of Nitrogen Isotope Fractionation during the Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds with Dissolved Reductants. Environmental Science and Technology 42(22), pp. 8352–8359. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es801063u DOI: 10.1021/es801063u]</ref><ref name="Kim2009">Kim, D., Duckworth, O.W., and Strathmann, T.J., 2009. Hydroxamate siderophore-promoted reactions between iron(II) and nitroaromatic groundwater contaminants. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73(5), pp. 1297–1311. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2008.11.039 DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.11.039]</ref><ref name="Kim2007">Kim, D., and Strathmann, T.J., 2007. Role of Organically Complexed Iron(II) Species in the Reductive Transformation of RDX in Anoxic Environments. Environmental Science and Technology, 41(4), pp. 1257–1264. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es062365a DOI: 10.1021/es062365a]</ref>, iron oxides in the presence of aqueous Fe(II)<ref name="Colón2006">Colón, D., Weber, E.J., and Anderson, J.L., 2006. QSAR Study of the Reduction of Nitroaromatics by Fe(II) Species. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(16), pp. 4976–4982. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es052425x DOI: 10.1021/es052425x]</ref><ref name="Luan2013">Luan, F., Xie, L., Li, J., and Zhou, Q., 2013. Abiotic reduction of nitroaromatic compounds by Fe(II) associated with iron oxides and humic acid. Chemosphere, 91(7), pp. 1035–1041. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.070 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.070]</ref><ref name="Gorski2016">Gorski, C.A., Edwards, R., Sander, M., Hofstetter, T.B., and Stewart, S.M., 2016. Thermodynamic Characterization of Iron Oxide–Aqueous Fe<sup>2+</sup> Redox Couples. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(16), pp. 8538–8547. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02661 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02661]</ref><ref name="Fan2016">Fan, D., Bradley, M.J., Hinkle, A.W., Johnson, R.L., and Tratnyek, P.G., 2016. Chemical Reactivity Probes for Assessing Abiotic Natural Attenuation by Reducing Iron Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(4), pp. 1868–1876. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05800 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05800]</ref><ref name="Jones2016">Jones, A.M., Kinsela, A.S., Collins, R.N., and Waite, T.D., 2016. The reduction of 4-chloronitrobenzene by Fe(II)-Fe(III) oxide systems - correlations with reduction potential and inhibition by silicate. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 320, pp. 143–149. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.031 DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.031]</ref><ref name="Klausen1995">Klausen, J., Troeber, S.P., Haderlein, S.B., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 1995. Reduction of Substituted Nitrobenzenes by Fe(II) in Aqueous Mineral Suspensions. Environmental Science and Technology, 29(9), pp. 2396–2404. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es00009a036 DOI: 10.1021/es00009a036]</ref><ref name="Strehlau2016">Strehlau, J.H., Stemig, M.S., Penn, R.L., and Arnold, W.A., 2016. Facet-Dependent Oxidative Goethite Growth As a Function of Aqueous Solution Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(19), pp. 10406–10412. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02436 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02436]</ref><ref name="Elsner2004">Elsner, M., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Haderlein, S.B., 2004. Reactivity of Fe(II)-Bearing Minerals toward Reductive Transformation of Organic Contaminants. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(3), pp. 799–807. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0345569 DOI: 10.1021/es0345569]</ref><ref name="Colón2008">Colón, D., Weber, E.J., and Anderson, J.L., 2008. Effect of Natural Organic Matter on the Reduction of Nitroaromatics by Fe(II) Species. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(17), pp. 6538–6543. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es8004249 DOI: 10.1021/es8004249]</ref><ref name="Stewart2018">Stewart, S.M., Hofstetter, T.B., Joshi, P. and Gorski, C.A., 2018. Linking Thermodynamics to Pollutant Reduction Kinetics by Fe<sup>2+</sup> Bound to Iron Oxides. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(10), pp. 5600–5609. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b00481 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00481] [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/acs.est.8b00481 Open access article.]</ref><ref name="Klupinski2004">Klupinski, T.P., Chin, Y.P., and Traina, S.J., 2004. Abiotic Degradation of Pentachloronitrobenzene by Fe(II): Reactions on Goethite and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(16), pp. 4353–4360. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es035434j DOI: 10.1021/es035434j]</ref>, magnetite<ref name="Klausen1995"/><ref name="Elsner2004"/><ref name="Heijman1993">Heijman, C.G., Holliger, C., Glaus, M.A., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Zeyer, J., 1993. Abiotic Reduction of 4-Chloronitrobenzene to 4-Chloroaniline in a Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Enrichment Culture. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 59(12), pp. 4350–4353. [https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.59.12.4350-4353.1993 DOI: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4350-4353.1993] [https://journals.asm.org/doi/reader/10.1128/aem.59.12.4350-4353.1993 Open access article.]</ref><ref name="Gorski2009">Gorski, C.A., and Scherer, M.M., 2009. Influence of Magnetite Stoichiometry on Fe<sup>II</sup> Uptake and Nitrobenzene Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(10), pp. 3675–3680. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es803613a DOI: 10.1021/es803613a]</ref><ref name="Gorski2010">Gorski, C.A., Nurmi, J.T., Tratnyek, P.G., Hofstetter, T.B. and Scherer, M.M., 2010. Redox Behavior of Magnetite: Implications for Contaminant Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(1), pp. 55–60. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es9016848 DOI: 10.1021/es9016848]</ref>, Fe(II)-bearing clays<ref name="Hofstetter2006">Hofstetter, T.B., Neumann, A., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2006. Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds by Fe(II) Species Associated with Iron-Rich Smectites. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(1), pp. 235–242. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0515147 DOI: 10.1021/es0515147]</ref><ref name="Schultz2000">Schultz, C. A., and Grundl, T.J., 2000. pH Dependence on Reduction Rate of 4-Cl-Nitrobenzene by Fe(II)/Montmorillonite Systems. Environmental Science and Technology 34(17), pp. 3641–3648. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es990931e DOI: 10.1021/es990931e]</ref><ref name="Luan2015a">Luan, F., Gorski, C.A., and Burgos, W.D., 2015. Linear Free Energy Relationships for the Biotic and Abiotic Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3557–3565. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es5060918 DOI: 10.1021/es5060918]</ref><ref name="Luan2015b">Luan, F., Liu, Y., Griffin, A.M., Gorski, C.A. and Burgos, W.D., 2015. Iron(III)-Bearing Clay Minerals Enhance Bioreduction of Nitrobenzene by ''Shewanella putrefaciens'' CN32. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(3), pp. 1418–1426. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es504149y DOI: 10.1021/es504149y]</ref><ref name="Hofstetter2003">Hofstetter, T.B., Schwarzenbach, R.P. and Haderlein, S.B., 2003. Reactivity of Fe(II) Species Associated with Clay Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology, 37(3), pp. 519–528. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es025955r DOI: 10.1021/es025955r]</ref><ref name="Neumann2008">Neumann, A., Hofstetter, T.B., Lüssi, M., Cirpka, O.A., Petit, S., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2008. Assessing the Redox Reactivity of Structural Iron in Smectites Using Nitroaromatic Compounds As Kinetic Probes. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(22), pp. 8381–8387. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es801840x DOI: 10.1021/es801840x]</ref><ref name="Hofstetter2008">Hofstetter, T.B., Neumann, A., Arnold, W.A., Hartenbach, A.E., Bolotin, J., Cramer, C.J., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2008. Substituent Effects on Nitrogen Isotope Fractionation During Abiotic Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(6), pp. 1997–2003. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es702471k DOI: 10.1021/es702471k]</ref>, hydroquinones (as surrogates of natural organic matter)<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/><ref name="Schwarzenbach1990">Schwarzenbach, R.P., Stierli, R., Lanz, K., and Zeyer, J., 1990. Quinone and Iron Porphyrin Mediated Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds in Homogeneous Aqueous Solution. Environmental Science and Technology, 24(10), pp. 1566–1574. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es00080a017 DOI: 10.1021/es00080a017]</ref><ref name="Tratnyek1989">Tratnyek, P.G., and Macalady, D.L., 1989. Abiotic Reduction of Nitro Aromatic Pesticides in Anaerobic Laboratory Systems. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 37(1), pp. 248–254. [https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00085a058 DOI: 10.1021/jf00085a058]</ref><ref name="Hofstetter1999">Hofstetter, T.B., Heijman, C.G., Haderlein, S.B., Holliger, C. and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 1999. Complete Reduction of TNT and Other (Poly)nitroaromatic Compounds under Iron-Reducing Subsurface Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology, 33(9), pp. 1479–1487. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es9809760 DOI: 10.1021/es9809760]</ref><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019">Murillo-Gelvez, J., Hickey, K.P., Di Toro, D.M., Allen, H.E., Carbonaro, R.F., and Chiu, P.C., 2019. Experimental Validation of Hydrogen Atom Transfer Gibbs Free Energy as a Predictor of Nitroaromatic Reduction Rate Constants. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(10), pp. 5816–5827. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b00910 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b00910]</ref><ref name="Niedźwiecka2017">Niedźwiecka, J.B., Drew, S.R., Schlautman, M.A., Millerick, K.A., Grubbs, E., Tharayil, N. and Finneran, K.T., 2017. Iron and Electron Shuttle Mediated (Bio)degradation of 2,4-Dinitroanisole (DNAN). Environmental Science and Technology, 51(18), pp. 10729–10735. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b02433 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02433]</ref><ref name="Kwon2006">Kwon, M.J., and Finneran, K.T., 2006. Microbially Mediated Biodegradation of Hexahydro-1,3,5-Trinitro-1,3,5- Triazine by Extracellular Electron Shuttling Compounds. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(9), pp. 5933–5941. [https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00660-06 DOI: 10.1128/AEM.00660-06] [https://journals.asm.org/doi/reader/10.1128/AEM.00660-06 Open access article.]</ref>, dissolved organic matter<ref name="Dunnivant1992">Dunnivant, F.M., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Macalady, D.L., 1992. Reduction of Substituted Nitrobenzenes in Aqueous Solutions Containing Natural Organic Matter. Environmental Science and Technology, 26(11), pp. 2133–2141. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es00035a010 DOI: 10.1021/es00035a010]</ref><ref name="Luan2010">Luan, F., Burgos, W.D., Xie, L., and Zhou, Q., 2010. Bioreduction of Nitrobenzene, Natural Organic Matter, and Hematite by Shewanella putrefaciens CN32. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(1), pp. 184–190. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es901585z DOI: 10.1021/es901585z]</ref><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021">Murillo-Gelvez, J., di Toro, D.M., Allen, H.E., Carbonaro, R.F., and Chiu, P.C., 2021. Reductive Transformation of 3-Nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) by Leonardite Humic Acid and Anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS). Environmental Science and Technology, 55(19), pp. 12973–12983. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c03333 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.1c03333]</ref>, black carbon<ref name="Oh2013">Oh, S.-Y., Son, J.G., and Chiu, P.C., 2013. Biochar-Mediated Reductive Transformation of Nitro Herbicides and Explosives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(3), pp. 501–508. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2087 DOI: 10.1002/etc.2087] [https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/etc.2087 Open access article.]</ref><ref name="Oh2009">Oh, S.-Y., and Chiu, P.C., 2009. Graphite- and Soot-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene and Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(18), pp. 6983–6988. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es901433m DOI: 10.1021/es901433m]</ref><ref name="Xu2015">Xu, W., Pignatello, J.J., and Mitch, W.A., 2015. Reduction of Nitroaromatics Sorbed to Black Carbon by Direct Reaction with Sorbed Sulfides. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3419–3426. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es5045198 DOI: 10.1021/es5045198]</ref><ref name="Oh2002">Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., and Chiu, P.C., 2002. Graphite-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene with Elemental Iron. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(10), pp. 2178–2184. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es011474g DOI: 10.1021/es011474g]</ref><ref name="Amezquita-Garcia2013">Amezquita-Garcia, H.J., Razo-Flores, E., Cervantes, F.J., and Rangel-Mendez, J.R., 2013. Activated carbon fibers as redox mediators for the increased reduction of nitroaromatics. Carbon, 55, pp. 276–284. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2012.12.062 DOI: 10.1016/j.carbon.2012.12.062]</ref><ref name="Xin2022">Xin, D., Girón, J., Fuller, M.E., and Chiu, P.C., 2022. Abiotic Reduction of 3-Nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) and Other Munitions Constituents by Wood-Derived Biochar through Its Rechargeable Electron Storage Capacity. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 24(2), pp. 316-329. [https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EM00447F DOI: 10.1039/D1EM00447F]</ref>, and sulfides<ref name="Hojo1960">Hojo, M., Takagi, Y. and Ogata, Y., 1960. Kinetics of the Reduction of Nitrobenzenes by Sodium Disulfide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 82(10), pp. 2459–2462. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01495a017 DOI: 10.1021/ja01495a017]</ref><ref name="Zeng2012">Zeng, T., Chin, Y.P., and Arnold, W.A., 2012. Potential for Abiotic Reduction of Pesticides in Prairie Pothole Porewaters. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(6), pp. 3177–3187. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es203584d DOI: 10.1021/es203584d]</ref>. These geo-reductants may control the fate and half-lives of MCs in the environment and can be used to promote MC degradation in soil and groundwater through enhanced natural attenuation<ref name="USEPA2012">US EPA, 2012. A Citizen’s Guide to Monitored Natural Attenuation. EPA document 542-F-12-014. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-04/documents/a_citizens_guide_to_monitored_natural_attenuation.pdf Free download.]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig2.png | thumb |450px|Figure 2. General mechanism for the reduction of NACs/MCs.]]

| |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig3.png | thumb |450px|Figure 3. Schematic of natural attenuation of MCs-impacted soils through chemical reduction.]]

| |

| − | Although the chemical structures of MCs can vary significantly (Figure 1), most of them contain at least one nitro functional group (-NO<sub>2</sub>), which is susceptible to reductive transformation<ref name="Spain2000">Spain, J.C., Hughes, J.B., and Knackmuss, H.J., 2000. Biodegradation of Nitroaromatic Compounds and Explosives. CRC Press, 456 pages. ISBN: 9780367398491</ref>. Of the MCs shown in Figure 1, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO)<ref name="Harris1996">Harris, N.J., and Lammertsma, K., 1996. Tautomerism, Ionization, and Bond Dissociations of 5-Nitro-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazolone. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 118(34), pp. 8048–8055. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja960834a DOI: 10.1021/ja960834a]</ref> are nitroaromatic compounds (NACs) and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) and nitroguanidine (NQ) are nitramines. The structural differences may result in different reactivities and reaction pathways. Reduction of NACs results in the formation of aromatic amines (i.e., anilines) with nitroso and hydroxylamine compounds as intermediates (Figure 2)<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Although the final reduction products are different for non-aromatic MCs, the reduction process often starts with the transformation of the -NO<sub>2</sub> moiety, either through de-nitration (e.g., RDX<ref name="Kwon2008">Kwon, M.J., and Finneran, K.T., 2008. Biotransformation products and mineralization potential for hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) in abiotic versus biological degradation pathways with anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) and ''Geobacter metallireducens''. Biodegradation, 19(5), pp. 705–715. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-008-9175-5 DOI: 10.1007/s10532-008-9175-5]</ref><ref name="Halasz2011">Halasz, A., and Hawari, J., 2011. Degradation Routes of RDX in Various Redox Systems. Aquatic Redox Chemistry, American Chemical Society, 1071(20), pp. 441-462. [https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2011-1071.ch020 DOI: 10.1021/bk-2011-1071.ch020]</ref>) or reduction to nitroso<ref name="Kwon2006"/><ref name="Tong2021">Tong, Y., Berens, M.J., Ulrich, B.A., Bolotin, J., Strehlau, J.H., Hofstetter, T.B., and Arnold, W.A., 2021. Exploring the Utility of Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis for Assessing Ferrous Iron-Mediated Reduction of RDX in the Subsurface. Environmental Science and Technology, 55(10), pp. 6752–6763. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c08420 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c08420]</ref> followed by ring cleavage<ref name="Kim2007"/><ref name="Halasz2011"/><ref name="Tong2021"/><ref name="Larese-Casanova2008">Larese-Casanova, P., and Scherer, M.M., 2008. Abiotic Transformation of Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) by Green Rusts. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(11), pp. 3975–3981. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es702390b DOI: 10.1021/es702390b]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Figure 3 illustrates a typical MC reduction reaction. A redox-active soil constituent, such as organic matter or iron mineral, donates electrons to an MC and transforms the nitro group into an amino group (R-NH<sub>2</sub>). The rate at which an MC is reduced can vary by many orders of magnitude depending on the soil constituent, the MC, the reduction potential (''E<sub>H</sub>'') and other media conditions<ref name="Borch2010">Borch, T., Kretzschmar, R., Kappler, A., Cappellen, P.V., Ginder-Vogel, M., Voegelin, A., and Campbell, K., 2010. Biogeochemical Redox Processes and their Impact on Contaminant Dynamics. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(1), pp. 15–23. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es9026248 DOI: 10.1021/es9026248] [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/es9026248 Open access article.]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The most prevalent reductants in soils are iron minerals and organic carbon such as that found in natural organic matter. It has been suggested that Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> and dissolved organic matter concentrations could serve as indicators of NAC reducibility in anaerobic sediments<ref name="Zhang2009">Zhang, H., and Weber, E.J., 2009. Elucidating the Role of Electron Shuttles in Reductive Transformations in Anaerobic Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(4), pp. 1042–1048. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es8017072 DOI: 10.1021/es8017072]</ref>. The following sections summarize these two classes of reductants separately and present advances in our understanding of the kinetics of NAC/MC reduction by these geo-reductants.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Carbonaceous Reductants==

| |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig4.png | thumb |600px|Figure 4. Chemical structure of commonly used hydroquinones in NACs/MCs kinetic experiments.]]

| |

| − | The two most predominant forms of organic carbon in natural systems are natural organic matter (NOM) and black carbon (BC)<ref name="Schumacher2002">Schumacher, B.A., 2002. Methods for the Determination of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) in Soils and Sediments. U.S. EPA, Ecological Risk Assessment Support Center. [http://bcodata.whoi.edu/LaurentianGreatLakes_Chemistry/bs116.pdf Free download.]</ref>. Black carbon includes charcoal, soot, graphite, and coal. Until the early 2000s black carbon was considered to be a class of (bio)chemically inert geosorbents<ref name="Schmidt2000">Schmidt, M.W.I., and Noack, A.G., 2000. Black carbon in soils and sediments: Analysis, distribution, implications, and current challenges. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 14(3), pp. 777–793. [https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GB001208 DOI: 10.1029/1999GB001208] [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/1999GB001208 Open access article.]</ref>. However, it has been shown that BC can contain abundant quinone functional groups and thus can store and exchange electrons<ref name="Klüpfel2014">Klüpfel, L., Keiluweit, M., Kleber, M., and Sander, M., 2014. Redox Properties of Plant Biomass-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar). Environmental Science and Technology, 48(10), pp. 5601–5611. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es500906d DOI: 10.1021/es500906d]</ref> with chemical<ref name="Xin2019">Xin, D., Xian, M., and Chiu, P.C., 2019. New methods for assessing electron storage capacity and redox reversibility of biochar. Chemosphere, 215, 827–834. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.080 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.080]</ref> and biological<ref name="Saquing2016">Saquing, J.M., Yu, Y.-H., and Chiu, P.C., 2016. Wood-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar) as a Microbial Electron Donor and Acceptor. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 3(2), pp. 62–66. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354 DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354]</ref> agents in the surroundings. Specifically, BC such as biochar has been shown to reductively transform MCs including NTO, DNAN, and RDX<ref name="Xin2022"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | NOM encompasses all the organic compounds present in terrestrial and aquatic environments and can be classified into two groups, non-humic and humic substances. Humic substances (HS) contain a wide array of functional groups including carboxyl, enol, ether, ketone, ester, amide, (hydro)quinone, and phenol<ref name="Sparks2003">Sparks, D.L., 2003. Environmental Soil Chemistry, 2nd Edition. Elsevier Science and Technology Books. [https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-656446-4.X5000-2 DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-656446-4.X5000-2]</ref>. Quinone and hydroquinone groups are believed to be the predominant redox moieties responsible for the capacity of HS and BC to store and reversibly accept and donate electrons (i.e., through reduction and oxidation of HS/BC, respectively)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/><ref name="Dunnivant1992"/><ref name="Klüpfel2014"/><ref name="Scott1998">Scott, D.T., McKnight, D.M., Blunt-Harris, E.L., Kolesar, S.E., and Lovley, D.R., 1998. Quinone Moieties Act as Electron Acceptors in the Reduction of Humic Substances by Humics-Reducing Microorganisms. Environmental Science and Technology, 32(19), pp. 2984–2989. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es980272q DOI: 10.1021/es980272q]</ref><ref name="Cory2005">Cory, R.M., and McKnight, D.M., 2005. Fluorescence Spectroscopy Reveals Ubiquitous Presence of Oxidized and Reduced Quinones in Dissolved Organic Matter. Environmental Science & Technology, 39(21), pp 8142–8149. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0506962 DOI: 10.1021/es0506962]</ref><ref name="Fimmen2007">Fimmen, R.L., Cory, R.M., Chin, Y.P., Trouts, T.D., and McKnight, D.M., 2007. Probing the oxidation–reduction properties of terrestrially and microbially derived dissolved organic matter. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 71(12), pp. 3003–3015. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.04.009 DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2007.04.009]</ref><ref name="Struyk2001">Struyk, Z., and Sposito, G., 2001. Redox properties of standard humic acids. Geoderma, 102(3-4), pp. 329–346. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(01)00040-4 DOI: 10.1016/S0016-7061(01)00040-4]</ref><ref name="Ratasuk2007">Ratasuk, N., and Nanny, M.A., 2007. Characterization and Quantification of Reversible Redox Sites in Humic Substances. Environmental Science and Technology, 41(22), pp. 7844–7850. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es071389u DOI: 10.1021/es071389u]</ref><ref name="Aeschbacher2010">Aeschbacher, M., Sander, M., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2010. Novel Electrochemical Approach to Assess the Redox Properties of Humic Substances. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(1), pp. 87–93. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es902627p DOI: 10.1021/es902627p]</ref><ref name="Aeschbacher2011">Aeschbacher, M., Vergari, D., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Sander, M., 2011. Electrochemical Analysis of Proton and Electron Transfer Equilibria of the Reducible Moieties in Humic Acids. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(19), pp. 8385–8394. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es201981g DOI: 10.1021/es201981g]</ref><ref name="Bauer2009">Bauer, I., and Kappler, A., 2009. Rates and Extent of Reduction of Fe(III) Compounds and O<sub>2</sub> by Humic Substances. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(13), pp. 4902–4908. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es900179s DOI: 10.1021/es900179s]</ref><ref name="Maurer2010">Maurer, F., Christl, I. and Kretzschmar, R., 2010. Reduction and Reoxidation of Humic Acid: Influence on Spectroscopic Properties and Proton Binding. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(15), pp. 5787–5792. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es100594t DOI: 10.1021/es100594t]</ref><ref name="Walpen2016">Walpen, N., Schroth, M.H., and Sander, M., 2016. Quantification of Phenolic Antioxidant Moieties in Dissolved Organic Matter by Flow-Injection Analysis with Electrochemical Detection. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(12), pp. 6423–6432. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b01120 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01120] [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/acs.est.6b01120 Open access article.]</ref><ref name="Aeschbacher2012">Aeschbacher, M., Graf, C., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Sander, M., 2012. Antioxidant Properties of Humic Substances. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(9), pp. 4916–4925. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es300039h DOI: 10.1021/es300039h]</ref><ref name="Nurmi2002">Nurmi, J.T., and Tratnyek, P.G., 2002. Electrochemical Properties of Natural Organic Matter (NOM), Fractions of NOM, and Model Biogeochemical Electron Shuttles. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(4), pp. 617–624. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0110731 DOI: 10.1021/es0110731]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Hydroquinones have been widely used as surrogates to understand the reductive transformation of NACs and MCs by NOM. Figure 4 shows the chemical structures of the singly deprotonated forms of four hydroquinone species previously used to study NAC/MC reduction. The second-order rate constants (''k<sub>R</sub>'') for the reduction of NACs/MCs by these hydroquinone species are listed in Table 1, along with the aqueous-phase one electron reduction potentials of the NACs/MCs (''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1’</sup>'') where available. ''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1’</sup>'' is an experimentally measurable thermodynamic property that reflects the propensity of a given NAC/MC to accept an electron in water (''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1</sup>''(R-NO<sub>2</sub>)):

| |

| − | | |

| − | :::::<big>'''Equation 1:''' ''R-NO<sub>2</sub> + e<sup>-</sup> ⇔ R-NO<sub>2</sub><sup>•-</sup>''</big>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Knowing the identity of and reaction order in the reductant is required to derive the second-order rate constants listed in Table 1. This same reason limits the utility of reduction rate constants measured with complex carbonaceous reductants such as NOM<ref name="Dunnivant1992"/>, BC<ref name="Oh2013"/><ref name="Oh2009"/><ref name="Xu2015"/><ref name="Xin2021">Xin, D., 2021. Understanding the Electron Storage Capacity of Pyrogenic Black Carbon: Origin, Redox Reversibility, Spatial Distribution, and Environmental Applications. Doctoral Thesis, University of Delaware. [https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/30105/Xin_udel_0060D_14728.pdf?sequence=1 Free download.]</ref>, and HS<ref name="Luan2010"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/>, whose chemical structures and redox moieties responsible for the reduction, as well as their abundance, are not clearly defined or known. In other words, the observed rate constants in those studies are specific to the experimental conditions (e.g., pH and NOM source and concentration), and may not be easily comparable to other studies.

| |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:40px; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+ Table 1. Aqueous phase one electron reduction potentials and logarithm of second-order rate constants for the reduction of NACs and MCs by the singly deprotonated form of the hydroquinones lawsone, juglone, AHQDS and AHQS, with the second-order rate constants for the deprotonated NAC/MC species (i.e., nitrophenolates and NTO<sup>–</sup>) in parentheses.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! Compound

| |

| − | ! rowspan="2" |''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1'</sup>'' (V)

| |

| − | ! colspan="4"| Hydroquinone (log ''k<sub>R</sub>'' (M<sup>-1</sup>s<sup>-1</sup>))

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! (NAC/MC)

| |

| − | ! LAW<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! JUG<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! AHQDS<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! AHQS<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitrobenzene (NB) || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.380<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.102<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.050<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 3.060<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrotoluene (2-NT) || -0.590<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.432<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -2.523<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.775<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitrotoluene (3-NT) || -0.475<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.462<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.921<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrotoluene (4-NT) || -0.500<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.292<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.822<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> || 2.610<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloronitrobenzene (2-ClNB) || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.342<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.824<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> ||2.412<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-chloronitrobenzene (3-ClNB) || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.491<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.114<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloronitrobenzene (4-ClNB) || -0.450<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.301<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.988<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-acetylnitrobenzene (2-AcNB) || -0.470<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.519<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.456<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-acetylnitrobenzene (3-AcNB) || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.663<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.398<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-acetylnitrobenzene (4-AcNB) || -0.360<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.519<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.477<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrophenol (2-NP) || || 0.568 (0.079)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) || || -0.699 (-1.301)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-methyl-2-nitrophenol (4-Me-2-NP) || || 0.748 (0.176)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloro-2-nitrophenol (4-Cl-2-NP) || || 1.602 (1.114)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 5-fluoro-2-nitrophenol (5-Cl-2-NP) || || 0.447 (-0.155)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) || -0.280<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 2.869<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || 5.204<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene (2-A-4,6-DNT) || -0.400<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 0.987<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene (4-A-2,6-DNT) || -0.440<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 0.079<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4-diamino-6-nitrotoluene (2,4-DA-6-NT) || -0.505<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || -1.678<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,6-diamino-4-nitrotoluene (2,6-DA-4-NT) || -0.495<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || -1.252<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,3-dinitrobenzene (1,3-DNB) || -0.345<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || 1.785<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,4-dinitrobenzene (1,4-DNB) || -0.257<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || 3.839<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitroaniline (2-NANE) || < -0.560<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || -2.638<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitroaniline (3-NANE) || -0.500<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || -1.367<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,2-dinitrobenzene (1,2-DNB) || -0.290<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || || 5.407<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitroanisole (4-NAN) || || -0.661<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.220<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-amino-4-nitroanisole (2-A-4-NAN) || || -0.924<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.150<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.190<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-amino-2-nitroanisole (4-A-2-NAN) || || || ||1.610<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.360<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloro-4-nitroaniline (2-Cl-5-NANE) || || -0.863<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.250<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.210<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | N-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA) || || -1.740<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || -0.260<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 0.692<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) || || || || 5.701 (1.914)<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) || || || || -0.349<ref name="Kwon2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig5.png | thumb |500px|Figure 5. Relative reduction rate constants of the NACs/MCs listed in Table 1 for AHQDS<sup>–</sup>. Rate constants are compared with respect to RDX. Abbreviations of NACs/MCs as listed in Table 1.]]

| |

| − | Most of the current knowledge about MC degradation is derived from studies using NACs. The reduction kinetics of only four MCs, namely TNT, N-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA), NTO, and RDX, have been investigated with hydroquinones. Of these four MCs, only the reduction rates of MNA and TNT have been modeled<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/><ref name="Riefler2000">Riefler, R.G., and Smets, B.F., 2000. Enzymatic Reduction of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene and Related Nitroarenes: Kinetics Linked to One-Electron Redox Potentials. Environmental Science and Technology, 34(18), pp. 3900–3906. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es991422f DOI: 10.1021/es991422f]</ref><ref name="Salter-Blanc2015">Salter-Blanc, A.J., Bylaska, E.J., Johnston, H.J., and Tratnyek, P.G., 2015. Predicting Reduction Rates of Energetic Nitroaromatic Compounds Using Calculated One-Electron Reduction Potentials. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3778–3786. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es505092s DOI: 10.1021/es505092s] [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/es505092s Open access article.]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Using the rate constants obtained with AHQDS<sup>–</sup>, a relative reactivity trend can be obtained (Figure 5). RDX is the slowest reacting MC in Table 1, hence it was selected to calculate the relative rates of reaction (i.e., log ''k<sub>NAC/MC</sub>'' – log ''k<sub>RDX</sub>''). If only the MCs in Figure 5 are considered, the reactivity spans 6 orders of magnitude following the trend: RDX ≈ MNA < NTO<sup>–</sup> < DNAN < TNT < NTO. The rate constant for DNAN reduction by AHQDS<sup>–</sup> is not yet published and hence not included in Table 1. Note that speciation of NACs/MCs can significantly affect their reduction rates. Upon deprotonation, the NAC/MC becomes negatively charged and less reactive as an oxidant (i.e., less prone to accept an electron). As a result, the second-order rate constant can decrease by 0.5-0.6 log unit in the case of nitrophenols and approximately 4 log units in the case of NTO (numbers in parentheses in Table 1)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/>.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Ferruginous Reductants==

| + | Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO<sub>3</sub><sup>2−</sup>) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as ''hv, SO<sub>3</sub><sup><big>'''•-'''</big></sup>'' is the sulfur trioxide radical anion): |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:right; margin-left:40px; text-align:center;"

| + | </br> |

| − | |+ Table 2. Logarithm of second-order rate constants for reduction of NACs and MCs by dissolved Fe(II) complexes with the stoichiometry of ligand and iron in square brackets

| + | ::<big>'''Equation 1:'''</big> [[File: XiongEq1.png | 200 px]] |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! Compound

| |

| − | ! E<sub>H</sub><sup>1'</sup> (V)

| |

| − | ! Cysteine</br>[FeL<sub>2</sub>]<sup>2-</sup>

| |

| − | ! Thioglycolic acid</br>[FeL<sub>2</sub>]<sup>2-</sup>

| |

| − | ! DFOB</br>[FeHL]<sup>0</sup>

| |

| − | ! AcHA</br>[FeL<sub>3</sub>]<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! Tiron</br>[FeL<sub>2</sub>]<sup>6-</sup>

| |

| − | ! Fe-Porphyrin

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitrobenzene || -0.485 j || -0.347 || 0.874 || 2.235 || -0.136 || 1.424 d/</br>4.000 e || -0.018 h</br>0.026 i

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrotoluene || -0.590 j || || || || || || -0.602 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitrotoluene || -0.475 j || -0.434 || 0.767 || 2.106 || -0.229 || 1.999 d</BR>3.800 e || 0.041 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrotoluene || -0.500 j || -0.652 || 0.528 || 2.013 || -0.402 || 1.446 d</br>3.500 e || -0.174 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloronitrobenzene || -0.485 j || || || || || || 0.944 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-chloronitrobenzene || -0.405 j || 0.360 || 1.810 || 2.888 || 0.691 || 2.882 d</br>4.900 e || 0.724 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloronitrobenzene || -0.450 j || 0.230 || 1.415 || 2.512 || 0.375 || 3.937 d</br>4.581 e || 0.431 h</br>0.289 i

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-acetylnitrobenzene || -0.470 j || || || || || || 1.377 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-acetylnitrobenzene || -0.405 j || || || || || || 0.799 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-acetylnitrobenzene || -0.360 j || 0.965 || 2.771 || || 1.872 || 5.028 d</br>6.300 e || 1.693 h

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX || -0.550 k || || || || || 2.212 d</br>2.864 f ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | HMX || -0.660 k || || || || || -2.762 d ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | TNT || -0.280 l || || || || || 7.427 d || 2.050 i

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,3-dinitrobenzene || -0.345 m || || || || || || 1.220 i

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4-dinitrotoluene || -0.380 n || || || || || 5.319 d || 1.156 i

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitroguanidine (NQ) || -0.700 o || || || || || -0.185 d ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN) || -0.400 k || || || || || || 1.243 i

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:40px; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+ Table 3. Rate constants for the reduction of MCs by iron minerals

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! MC

| |

| − | ! Iron Mineral

| |

| − | ! Iron mineral loading</br>(g/L)

| |

| − | ! Surface area</br>(m<sup>2</sup>/g)

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> initial</br>(mM) ''<sup>b</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> after 24 h</br>(mM) ''<sup>c</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> sorbed</br>(mM) ''<sup>d</sup>''

| |

| − | ! pH

| |

| − | ! Buffer

| |

| − | ! Buffer</br>(mM)

| |

| − | ! MC initial</br>(μM) ''<sup>e</sup>''

| |

| − | ! log ''k<sub>obs</sub>''</br>(h<sup>-1</sup>) ''<sup>f</sup>''

| |

| − | ! log ''k<sub>SA</sub>''</br>(Lh<sup>-1</sup>m<sup>-2</sup>) ''<sup>g</sup>''

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | TNT 29 || Goethite || 0.64 || 17.5 || 1.5 || || || 7.0 || MOPS || 25 || 50 || 1.200 || 0.170

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 0.1 || 0 || 0.10 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -3.500 || -5.200

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 0.2 || 0.02 || 0.18 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -2.900 || -4.500

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 0.5 || 0.23 || 0.27 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.900 || -3.600

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.5 || 0.94 || 0.56 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.400 || -3.100

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 3.0 || 1.74 || 1.26 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.200 || -2.900

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 5.0 || 3.38 || 1.62 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.100 || -2.800

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 10.0 || 7.77 || 2.23 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.000 || -2.600

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.42 || 0.16 || 6.0 || MES || 50 || 50 || -2.700 || -4.300

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.34 || 0.24 || 6.5 || MOPS || 50 || 50 || -1.800 || -3.400

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.21 || 0.37 || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 50 || -1.200 || -2.900

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.01 || 0.57 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.200 || -2.800

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 0.76 || 0.82 || 7.5 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -0.490 || -2.100

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 80 || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 0.56 || 1.01 || 8.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -0.590 || -2.200

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NG 82 || Magnetite || 4.00 || 0.56|| 4.0 || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 90 || 226 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NG 85 || Pyrite || 20.00 || 0.53 || || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 100 || 307 || -2.213 || -3.238

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | TNT 85 || Pyrite || 20.00 || 0.53 || || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 100 || 242 || -2.812 || -3.837

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 85 || Pyrite || 20.00 || 0.53 || || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 100 || 201 || -3.058 || -4.083

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 51 || Carbonate Green Rust || 5.00 || 36 || || || || 7.0 || || || 100 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 51 || Sulfate Green Rust || 5.00 || 20 || || || || 7.0 || || || 100 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 83 || Sulfate Green Rust || 10.00 || || || || || 8.4 || || || 500 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 83 || Sulfate Green Rust || 10.00 || || || || || 8.4 || || || 500 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 81 || Magnetite || 2.00 || 17.8 || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 200 || -0.100 || -1.700

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 81 || Mackinawite || 1.50 || || || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 200 || 0.061 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 81 || Goethite || 1.00 || 103.8 || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 200 || 0.410 || -1.600

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 88 || Magnetite || 0.62 || || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 17.5 || -1.100 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 88 || Magnetite || 0.62 || || || || || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 17.5 || -0.270 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 88 || Magnetite || 0.62 || || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || MOPS || 10 || 17.6 || -0.480 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.92 || 0.08 || 5.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || -0.550 || -1.308

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.85 || 0.15 || 6.0 || MES || 50 || 30 || 0.619 || -0.140

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.9 || 0.10 || 6.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || 1.348 || 0.590

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.77 || 0.23 || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 30 || 2.167 || 1.408

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 1.01 || || 5.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || -1.444 || -2.200

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 0.97 || || 6.0 || MES || 50 || 30 || -0.658 || -1.413

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 0.87 || || 6.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || 0.068 || -0.688

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 89 || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 0.79 || || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 30 || 1.210 || 0.456

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Mackinawite || 0.45 || || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.092 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Mackinawite || 0.45 || || || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || 0.009 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Mackinawite || 0.45 || || || || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || 0.158 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Green Rust || 5 || || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -1.301 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Green Rust || 5 || || || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -1.097 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Green Rust || 5 || || || || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.745 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Goethite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.921 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Goethite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.347 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Goethite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || 0.009 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Hematite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.824 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Hematite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.456 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Hematite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.237 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Magnetite || 2 || || 1 || 1 || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -1.523 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Magnetite || 2 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.824 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX 50 || Magnetite || 2 || 1 || 1 || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.229 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 84 || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.836 || 0.806

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 84 || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.762 || 0.732

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 84 || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.477 || 0.447

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN 84 || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.745 || 0.716

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 84 || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.663 || 0.633

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 84 || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.521 || 0.491

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 84 || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.492 || 0.462

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO 84 || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.427 || 0.398

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | Iron(II) can be complexed by a myriad of organic ligands and may thereby become more reactive towards MCs and other pollutants. The reactivity of an Fe(II)-organic complex depends on the relative preference of the organic ligand for Fe(III) versus Fe(II)<ref name="Kim2009"/>. Since the majority of naturally occurring ligands complex Fe(III) more strongly than Fe(II), the reduction potential of the resulting Fe(III) complex is lower than that of aqueous Fe(III); therefore, complexation by organic ligands often renders Fe(II) a stronger reductant thermodynamically<ref name="Strathmann2011">Strathmann, T.J., 2011. Redox Reactivity of Organically Complexed Iron(II) Species with Aquatic Contaminants. Aquatic Redox Chemistry, American Chemical Society,1071(14), pp. 283-313. [https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2011-1071.ch014 DOI: 10.1021/bk-2011-1071.ch014]</ref>. The reactivity of dissolved Fe(II)-organic complexes towards NACs/MCs has been investigated. The intrinsic, second-order rate constants and one electron reduction potentials are listed in Table 2.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In addition to forming organic complexes, iron is ubiquitous in minerals. Iron-bearing minerals play an important role in controlling the environmental fate of contaminants through adsorption<ref name="Linker2015">Linker, B.R., Khatiwada, R., Perdrial, N., Abrell, L., Sierra-Alvarez, R., Field, J.A., and Chorover, J., 2015. Adsorption of novel insensitive munitions compounds at clay mineral and metal oxide surfaces. Environmental Chemistry, 12(1), pp. 74–84. [https://doi.org/10.1071/EN14065 DOI: 10.1071/EN14065]</ref><ref name="Jenness2020">Jenness, G.R., Giles, S.A., and Shukla, M.K., 2020. Thermodynamic Adsorption States of TNT and DNAN on Corundum and Hematite. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 124(25), pp. 13837–13844. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c04512 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c04512]</ref> and reduction<ref name="Gorski2011">Gorski, C.A., and Scherer, M.M., 2011. Fe<sup>2+</sup> Sorption at the Fe Oxide-Water Interface: A Revised Conceptual Framework. Aquatic Redox Chemistry, American Chemical Society, 1071(15), pp. 315–343. [https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2011-1071.ch015 DOI: 10.1021/bk-2011-1071.ch015]</ref> processes. Studies have shown that aqueous Fe(II) itself cannot reduce NACs/MCs at circumneutral pH<ref name="Klausen1995"/><ref name="Gregory2004">Gregory, K.B., Larese-Casanova, P., Parkin, G.F., and Scherer, M.M., 2004. Abiotic Transformation of Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine by Fe<sup>II</sup> Bound to Magnetite. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(5), pp. 1408–1414. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es034588w DOI: 10.1021/es034588w]</ref> but in the presence of an iron oxide (e.g., goethite, hematite, lepidocrocite, ferrihydrite, or magnetite), NACs<ref name="Colón2006"/><ref name="Klausen1995"/><ref name="Strehlau2016"/><ref name="Elsner2004"/><ref name="Hofstetter2006"/> and MCs such as TNT<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/>, RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/>, DNAN<ref name="Berens2019">Berens, M.J., Ulrich, B.A., Strehlau, J.H., Hofstetter, T.B., and Arnold, W.A., 2019. Mineral identity, natural organic matter, and repeated contaminant exposures do not affect the carbon and nitrogen isotope fractionation of 2,4-dinitroanisole during abiotic reduction. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 21(1), pp. 51-62. [https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EM00381E DOI: 10.1039/C8EM00381E]</ref>, and NG<ref name="Oh2004">Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., and Chiu, P.C., 2004. Reduction of Nitroglycerin with Elemental Iron: Pathway, Kinetics, and Mechanisms. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(13), pp. 3723–3730. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0354667 DOI: 10.1021/es0354667]</ref> can be rapidly reduced. Unlike ferric oxides, Fe(II)-bearing minerals including clays<ref name="Hofstetter2006"/><ref name="Schultz2000"/><ref name="Luan2015a"/><ref name="Luan2015b"/><ref name="Hofstetter2003"/><ref name="Neumann2008"/><ref name="Hofstetter2008"/>, green rust<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/><ref name="Khatiwada2018">Khatiwada, R., Root, R.A., Abrell, L., Sierra-Alvarez, R., Field, J.A., and Chorover, J., 2018. Abiotic reduction of insensitive munition compounds by sulfate green rust. Environmental Chemistry, 15(5), pp. 259–266. [https://doi.org/10.1071/EN17221 DOI: 10.1071/EN17221]</ref>, mackinawite<ref name="Elsner2004"/><ref name="Berens2019"/><ref name="Menezes2021">Menezes, O., Yu, Y., Root, R.A., Gavazza, S., Chorover, J., Sierra-Alvarez, R., and Field, J.A., 2021. Iron(II) monosulfide (FeS) minerals reductively transform the insensitive munitions compounds 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN) and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO). Chemosphere, 285, p. 131409. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131409 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131409]</ref> and pyrite<ref name="Elsner2004"/><ref name="Oh2008">Oh, S.-Y., Chiu, P.C., and Cha, D.K., 2008. Reductive transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, and nitroglycerin by pyrite and magnetite. Journal of hazardous materials, 158(2-3), pp. 652–655. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.01.078 DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.01.078]</ref> do not need aqueous Fe(II) to be reactive toward NACs/MCs. However, upon oxidation, sulfate green rust was converted into lepidocrocite<ref name="Khatiwada2018"/>, and mackinawite into goethite<ref name="Menezes2021"/>, suggesting that aqueous Fe(II) coupled to Fe(III) oxides might be at least partially responsible for continued degradation of NACs/MCs in the subsurface once the parent reductant (e.g., green rust or iron sulfide) oxidizes.

| + | The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)]], [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanoic acid|perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)]]<ref>Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197]</ref> and [[Wikipedia: GenX|GenX]]<ref>Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02172 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172]</ref>. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., [[Wikipedia: Decarboxylation | decarboxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Hydroxylation | hydroxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Elimination reaction | elimination]], and [[Wikipedia: Hydrolysis | hydrolysis]])<ref name="BentelEtAl2019"/>. |

| | | | |

| − | The reaction conditions and rate constants for a list of studies on MC reduction by iron oxide-aqueous Fe(II) redox couples and by other Fe(II)-containing minerals are shown in Table 3<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/><ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/><ref name="Gregory2004"/><ref name="Berens2019"/><ref name="Oh2008"/><ref name="Strehlau2018">Strehlau, J.H., Berens, M.J., and Arnold, W.A., 2018. Mineralogy and buffer identity effects on RDX kinetics and intermediates during reaction with natural and synthetic magnetite. Chemosphere, 213, pp. 602–609. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.139 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.139]</ref><ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020">Cárdenas-Hernandez, P.A., Anderson, K.A., Murillo-Gelvez, J., di Toro, D.M., Allen, H.E., Carbonaro, R.F., and Chiu, P.C., 2020. Reduction of 3-Nitro-1,2,4-Triazol-5-One (NTO) by the Hematite–Aqueous Fe(II) Redox Couple. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(19), pp. 12191–12201. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c03872 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c03872]</ref>. Unlike hydroquinones and Fe(II) complexes, where second-order rate constants can be readily calculated, the reduction rate constants of NACs/MCs in mineral suspensions are often specific to the experimental conditions used and are usually reported as BET surface area-normalized reduction rate constants (''k<sub>SA</sub>''). In the case of iron oxide-Fe(II) redox couples, reduction rate constants have been shown to increase with pH (specifically, with [OH<sup>– </sup>]<sup>2</sup>) and aqueous Fe(II) concentration, both of which correspond to a decrease in the system's reduction potential<ref name="Colón2006"/><ref name="Gorski2016"/><ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/>.

| + | ==Process Description== |

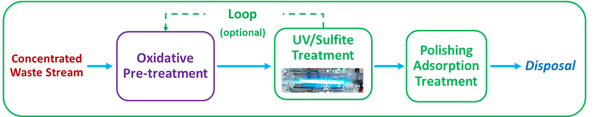

| | + | A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and a main treatment step to break C-F bonds by UV/sulfite reduction. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a [[Wikipedia: Foam fractionation | foam fractionation]], [[PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange | regenerable ion exchange]], or a [[Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membrane Filtration Systems for PFAS Removal | membrane filtration system]]) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1. [[File: XiongFig1.png | thumb | left | 600 px | Figure 1: Conceptual Treatment Process for a Concentrated PFAS Stream]]<br clear="left"/> |

| | | | |

| − | For minerals that contain structural iron(II) and can reduce pollutants in the absence of aqueous Fe(II), the observed rates of reduction increased with increasing structural Fe(II) content, as seen with iron-bearing clays<ref name="Luan2015a"/><ref name="Luan2015b"/> and green rust<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/>. This dependency on Fe(II) content allows for the derivation of second-order rate constants, as shown on Table 3 for the reduction of RDX by green rust<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/>, and the development of reduction potential (E<sub>H</sub>)-based models<ref name="Luan2015a"/><ref name="Gorski2012a">Gorski, C.A., Aeschbacher, M., Soltermann, D., Voegelin, A., Baeyens, B., Marques Fernandes, M., Hofstetter, T.B., and Sander, M., 2012. Redox Properties of Structural Fe in Clay Minerals. 1. Electrochemical Quantification of Electron-Donating and -Accepting Capacities of Smectites. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(17), pp. 9360–9368. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3020138 DOI: 10.1021/es3020138]</ref><ref name="Gorski2012b">Gorski, C.A., Klüpfel, L., Voegelin, A., Sander, M., and Hofstetter, T.B., 2012. Redox Properties of Structural Fe in Clay Minerals. 2. Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Characterization of Electron Transfer Irreversibility in Ferruginous Smectite, SWa-1. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(17), pp. 9369–9377. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es302014u DOI: 10.1021/es302014u]</ref><ref name="Gorski2013">Gorski, C.A., Klüpfel, L.E., Voegelin, A., Sander, M. and Hofstetter, T.B., 2013. Redox Properties of Structural Fe in Clay Minerals: 3. Relationships between Smectite Redox and Structural Properties. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(23), pp. 13477–13485. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es403824x DOI: 10.1021/es403824x]</ref>, where E<sub>H</sub> represents the reduction potential of the iron-bearing clays. Iron-bearing expandable clay minerals represent a special case, which in addition to reduction can remove NACs/MCs through adsorption. This is particularly important for planar NACs/MCs that contain multiple electron-withdrawing nitro groups and can form strong electron donor-acceptor (EDA) complexes with the clay surface<ref name="Hofstetter2006"/><ref name="Hofstetter2003"/><ref name="Neumann2008"/>.

| + | ==Advantages== |

| | + | A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by ''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'', low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below: |

| | + | *'''High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS:''' While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies<ref>Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452]</ref><ref>Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02158 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158]</ref><ref>Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170]</ref>, the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including [[Wikipedia: Trifluoroacetic acid | trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluoropropionic acid | perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA)]]. |

| | + | *'''High defluorination ratio:''' As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions. |

| | + | *'''No harmful byproducts:''' While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts. |

| | + | *'''Ambient pressure and low temperature:''' The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS. |

| | + | *'''Low energy consumption:''' The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of [[Wikipedia: Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids | perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs)]] by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., [[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO) | supercritical water oxidation]])<ref>Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916]</ref>. |

| | + | *'''Co-contaminant destruction:''' The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride<ref>Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026]</ref><ref>Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086]</ref><ref>Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3008535 doi: 10.1021/es3008535]</ref><ref>Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051]</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | Although the second-order rate constants derived for Fe(II)-bearing minerals may allow comparison among different studies, they may not reflect changes in reactivity due to variations in surface area, pH, and the presence of ions. Anions such as bicarbonate<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/><ref name="Strehlau2018"/><ref name="Chen2020">Chen, G., Hofstetter, T.B., and Gorski, C.A., 2020. Role of Carbonate in Thermodynamic Relationships Describing Pollutant Reduction Kinetics by Iron Oxide-Bound Fe<sup>2+</sup>. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(16), pp. 10109–10117. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02959 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02959]</ref> and phosphate<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/><ref name="Bocher2004">Bocher, F., Géhin, A., Ruby, C., Ghanbaja, J., Abdelmoula, M., and Génin, J.M.R., 2004. Coprecipitation of Fe(II–III) hydroxycarbonate green rust stabilised by phosphate adsorption. Solid State Sciences, 6(1), pp. 117–124. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2003.10.004 DOI: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2003.10.004]</ref> are known to decrease the reactivity of iron oxides-Fe(II) redox couples and green rust. Sulfite has also been shown to decrease the reactivity of hematite-Fe(II) towards the deprotonated form of NTO (Table 3)<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/>. Exchanging cations in iron-bearing clays can change the reactivity of these minerals by up to 7-fold<ref name="Hofstetter2006"/>. Thus, more comprehensive models are needed to account for the complexities in the subsurface environment.

| + | ==Limitations== |

| | + | Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed. |

| | + | *Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success. |

| | + | *Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents. |

| | + | *The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS)]] exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds. |

| | | | |

| − | The reduction of NACs has been widely studied in the presence of different iron minerals, pH, and Fe(II)<sub>(aq)</sub> concentrations (Table 4)<ref name="Colón2006"/><ref name="Klausen1995"/><ref name="Strehlau2016"/><ref name="Elsner2004"/><ref name="Hofstetter2006"/>. Only selected NACs are included in Table 4. For more information on other NACs and ferruginous reductants, please refer to the cited references.

| + | ==State of the Practice== |

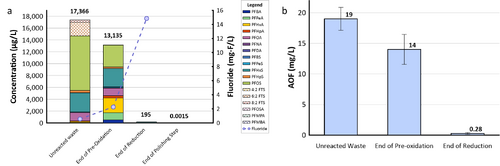

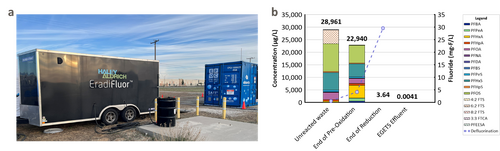

| | + | [[File: XiongFig2.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 2. Field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> for PFAS destruction in a concentrated waste stream in a Mid-Atlantic Naval Air Station: a) Target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99% of PFAS were destroyed; meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 15 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective PFAS destruction; b) AOF concentrations at each step of the treatment provided additional evidence to show near-complete mineralization of PFAS. Average results from multiple batches of treatment are shown here.]] |