|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | I have installed SandboxLink extension that provides each user their own sandbox accessible through their personal menu bar (top right) | | I have installed SandboxLink extension that provides each user their own sandbox accessible through their personal menu bar (top right) |

| | | | |

| − | Simple table

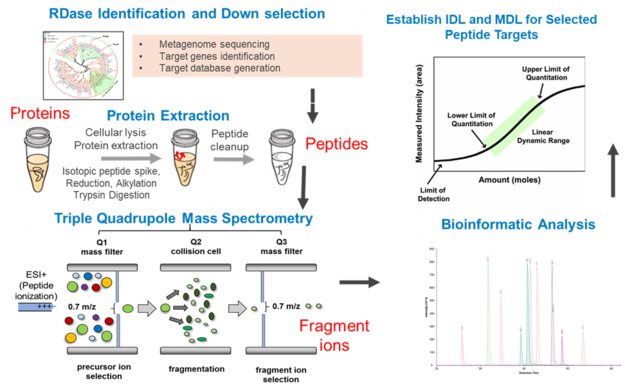

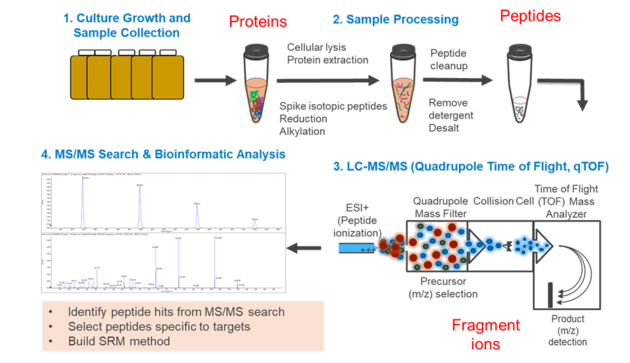

| + | Proteomics is the analysis of proteins present in a sample. Proteogenomics is the combined use of proteomics with genomics and transcriptomics to support protein identifications and analyses. As tools, proteomics and proteogenomics allow researchers and practitioners to understand the functional gene products and relevant microbial metabolisms in a system, which in turn can lead to informed decision-making in remediation situations. |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left: 10px;"

| |

| − | | See Also

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | *text

| |

| − | | |

| − | *more text

| |

| − | | |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | TABLE Edits below this line

| |

| − | | |

| − | <!-- class="wikitable" -->

| |

| − | {| class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed wikitable" style="margin: auto; color:black; background-color:white; width: 80%;"

| |

| − | |+Table 1. Nomenclature and Structure of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents <ref name="CS 2010">Cwiertny, D. M. and M.M. Scherer, 2010. Chapter 2, Chlorinated Solvent Chemistry: Structures, Nomenclature and Properties. In: HF Stroo and CH.Ward (eds.). In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. Springer, pp. 29-37. ISBN: 978-0-387-23036-8/e-ISBN: 978-0-387-23079-5, DOI: 10.1007/0-387-23079-3_32</ref>

| |

| − | |- style="color:white; background-color:#006699; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | | IUPAC Name

| |

| − | | Common Name

| |

| − | | Acronym

| |

| − | | Molecular Formula

| |

| − | | Chemical Structure

| |

| − | | Formula Weight

| |

| − | | Density (ρ)(g/mL)

| |

| − | | Solubility (mg/L)

| |

| − | | Vapor Pressure (ρ<sup>0</sup>)(kPa)

| |

| − | | Henry's Law Constant (K<sub>H</sub>)(x10<sup>-3</sup>atm・m<sup>3</sup>/mol)

| |

| − | | Log K<sub>ow</sub>

| |

| − | | MCL<sup>c</sup> (μg/L)

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Methanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|carbon tetrachloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| CT

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CCl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Tetrachloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|153.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.59

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|800

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|20.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|28.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.64

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|chloroform

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CF

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CHCl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trichloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|119.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.97

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.080<sup>d</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|dichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methylene chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|DCM

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CH<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Dichloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|84.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.33

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|13,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|55.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methyl chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CM

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CH<sub>3</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,235

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|570

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR<sup>e</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|hexachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|perchloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|HCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>6</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:hexachloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|236.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.09

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.05<sup>f</sup>

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|pentachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|PCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>HCl<sub>5</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:pentachloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|202.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.68

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.89

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,1,2-TeCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,1,2-Tetrachloroethane.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.54

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,2,2-TeCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.60

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,962

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.39

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,2-TCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,2-Trichloroethane.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,394

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.96

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methyl chloroform

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,1-TCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,1-trichloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.35

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,495

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|14.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.20

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,2-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,2-DCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,2-dichloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,606

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|10.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.48

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1-DCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1-Dichloroethane 2.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.17

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,676

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|30.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.79

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>5</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|64.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,700

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.43

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethenes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|perchloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|PCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Tetrachloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|165.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.63

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|150

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.88

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|TCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>HCl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trichloroethene.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|131.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.46

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|11.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.53

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>cis</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>cis</i>-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>cis</i>-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Cis-1,2-dichloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.28

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3,500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|27.1

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|7.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.86

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.07

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>trans</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>trans</i>-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>trans</i>-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trans-1,2-dichloroethene.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.26

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6,260

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|44.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.1

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|vinylidene chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1-Dichloroethene.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3,344

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|80.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|23.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.13

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.007

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|vinyl chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|VC

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|62.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,763

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|355

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|79.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.002

| |

| − |

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The chlorinated solvents and many of their transformation products are colorless liquids at room temperature. They are heavier than water with densities greater than 1 gram per cubic centimeter (g/cm<sub>3</sub>) which means they can penetrate deeply into an aquifer. Some physical and chemical properties of most widely used chlorinated solvents are listed in Table 2.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right: 40px; color:black; background-color:white; width: 60%;"

| |

| − | |+Table 2. Physical and Chemical Properties of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents at 25°C. Unless otherwise noted, all values have been taken from Mackay et al. (1993) <ref name="CS 2010" />

| |

| − | |- style="color:white; background-color:#006699; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | | Species

| |

| − | | Formula Weight

| |

| − | | Density (ρ)(g/mL)

| |

| − | | Solubility (mg/L)

| |

| − | | Vapor Pressure (ρ<sup>0</sup>)(kPa)

| |

| − | | Henry's Law Constant (K<sub>H</sub>)(x10<sup>-3</sup>atm・m<sup>3</sup>/mol)

| |

| − | | Log K<sub>ow</sub>

| |

| − | | MCL<sup>c</sup> (μg/L)

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Methanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|153.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.59

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|800

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|20.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|28.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.64

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|119.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.97

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.080<sup>d</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|dichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|84.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.33

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|13,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|55.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,235

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|570

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR<sup>e</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|hexachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|236.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.09

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.05<sup>f</sup>

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|pentachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|202.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.68

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.89

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.54

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.60

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,962

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.39

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,394

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.96

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.35

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,495

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|14.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.20

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,2-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,606

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|10.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.48

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.17

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,676

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|30.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.79

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|64.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,700

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.43

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethenes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|165.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.63

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|150

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.88

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|131.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.46

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|11.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.53

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>cis</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.28

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3,500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|27.1

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|7.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.86

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.07

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>trans</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.26

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6,260

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|44.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.1

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3,344

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|80.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|23.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.13

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.007

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|62.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,763

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|355

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|79.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.002

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − |

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | TABLE Edits above this line

| |

| − | | |

| − | <!-- class="wikitable" -->

| |

| − | {| class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right: 40px; color:black; background-color:white; width: 60%;"

| |

| − | |+Table 1. Nomenclature and Structure of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents <ref name="CS 2010">Cwiertny, D. M. and M.M. Scherer, 2010. Chapter 2, Chlorinated Solvent Chemistry: Structures, Nomenclature and Properties. In: HF Stroo and CH.Ward (eds.). In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. Springer, pp. 29-37. ISBN: 978-0-387-23036-8/e-ISBN: 978-0-387-23079-5, DOI: 10.1007/0-387-23079-3_32</ref>

| |

| − | |- style="color:white; background-color:#006699; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | | IUPAC Name

| |

| − | | Common Name

| |

| − | | Acronym

| |

| − | | Molecular Formula

| |

| − | | Chemical Structure

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="5" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Methanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|carbon tetrachloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| CT

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CCl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Tetrachloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|chloroform

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CF

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CHCl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trichloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|dichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methylene chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|DCM

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CH<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Dichloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methyl chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CM

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CH<sub>3</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="5" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|hexachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|perchloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|HCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>6</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:hexachloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|pentachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|PCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>HCl<sub>5</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:pentachloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,1,2-TeCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,1,2-Tetrachloroethane.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,2,2-TeCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,2-TCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,2-Trichloroethane.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methyl chloroform

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,1-TCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,1-trichloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,2-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,2-DCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,2-dichloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1-DCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1-Dichloroethane 2.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>5</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="5" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethenes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|perchloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|PCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Tetrachloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|TCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>HCl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trichloroethene.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>cis</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>cis</i>-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>cis</i>-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Cis-1,2-dichloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>trans</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>trans</i>-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>trans</i>-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trans-1,2-dichloroethene.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|vinylidene chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1-Dichloroethene.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|vinyl chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|VC

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The chlorinated solvents and many of their transformation products are colorless liquids at room temperature. They are heavier than water with densities greater than 1 gram per cubic centimeter (g/cm<sub>3</sub>) which means they can penetrate deeply into an aquifer. Some physical and chemical properties of most widely used chlorinated solvents are listed in Table 2.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right: 40px; color:black; background-color:white; width: 60%;"

| |

| − | |+Table 2. Physical and Chemical Properties of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents at 25°C. Unless otherwise noted, all values have been taken from Mackay et al. (1993) <ref name="CS 2010" />

| |

| − | |- style="color:white; background-color:#006699; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | | Species

| |

| − | | Formula Weight

| |

| − | | Density (ρ)(g/mL)

| |

| − | | Solubility (mg/L)

| |

| − | | Vapor Pressure (ρ<sup>0</sup>)(kPa)

| |

| − | | Henry's Law Constant (K<sub>H</sub>)(x10<sup>-3</sup>atm・m<sup>3</sup>/mol)

| |

| − | | Log K<sub>ow</sub>

| |

| − | | MCL<sup>c</sup> (μg/L)

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Methanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|153.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.59

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|800

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|20.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|28.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.64

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|119.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.97

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.080<sup>d</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|dichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|84.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.33

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|13,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|55.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,235

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|570

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR<sup>e</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|hexachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|236.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.09

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.05<sup>f</sup>

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|pentachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|202.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.68

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.89

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.54

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.60

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,962

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.39

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,394

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.96

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.35

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,495

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|14.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.20

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,2-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,606

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|10.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.48

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.17

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,676

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|30.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.79

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|64.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,700

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.43

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethenes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|165.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.63

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|150

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.88

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|131.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.46

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|11.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.53

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>cis</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.28

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3,500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|27.1

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|7.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.86

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.07

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>trans</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.26

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6,260

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|44.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.1

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3,344

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|80.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|23.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.13

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.007

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|62.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,763

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|355

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|79.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.002

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − |

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Review these links later:

| |

| − | http://www.navfac.navy.mil/navfac_worldwide/specialty_centers/exwc/products_and_services/ev/erb/tech/t2.html#hdbks

| |

| − | http://www.navfac.navy.mil/navfac_worldwide/specialty_centers/exwc/products_and_services/ev/erb/tech/t2.html#hdbks

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | <div class="toccolours mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" style="width:80%">

| |

| − | Table 2. Physical and Chemical Properties of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents at 25°C.<br>Unless otherwise noted, all values have been taken from Mackay et al. (1993) <ref name="CS 2010">Cwiertny, D. M. and M.M. Scherer, 2010. Chapter 2, Chlorinated Solvent Chemistry: Structures, Nomenclature and Properties. In: HF Stroo and CH.Ward (eds.). In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. Springer, pp. 29-37. ISBN: 978-0-387-23036-8/e-ISBN: 978-0-387-23079-5, DOI: 10.1007/0-387-23079-3_32</ref>

| |

| − | <div class="mw-collapsible-content">

| |

| − | [[File:Table 2 Chlorinated Solvents.JPG|frameless|center|800px|TABLE 2]]

| |

| − | </div>

| |

| − | </div>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | <!-- This div allows the TOC to float right -->

| |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | + | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| | + | *[[Molecular Biological Tools - MBTs]] |

| | + | *[[Metagenomics]] |

| | | | |

| − | CONTRIBUTOR(S):

| + | '''Contributor(s):''' Kate H. Kucharzyk, Ph.D., Morgan V. Evans, Ph.D., Robert W. Murdoch, Ph.D., Fadime Kara Murdoch, Ph.D. |

| − | | |

| − | *[[Dr. Bilgen Yuncu, P.E.]]

| |

| − | *[[M. Tony Lieberman]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==INTRODUCTION==

| |

| − | | |

| − | Chlorinated solvents are a large family of organic solvents that contain chlorine chlorine atoms in their molecular structure. They were first produced in Germany in the 1800s, and widespread use in the United States (U.S.) began after World War II. In the period of 1940-1980, the U.S. produced about 2 billion pounds of chlorinated solvents each year <ref name="PC 1996"> Pankow, J.F. and Cherry, J.A., 1996. Dense Chlorinated Solvents and Other DNAPLs in Groundwater, Waterloo Press, Portland, OR. ISBN-10: 0964801418/ISBN-13: 978-0964801417 </ref>. Chlorinated solvents, including [[wikipedia:Carbon_tetrachloride|carbon tetrachloride (CT)]], [[wikipedia:1,1,1-Trichloroethane|1,1,1-trichloroethane (TCA)]], [[wikipedia:Tetrachloroethylene|perchloroethene or tetrachloroethene (PCE)]] and [[wikipedia:Trichloroethylene|trichloroethene (TCE)]] have been among the most widely used cleaning and degreasing solvents in the U.S <ref> Doherty RE 2000. A history of the production and use of carbon tetrachloride, tetrachloroethylene, trichloroethylene and 1,1,1-trichloroethane in the United States: Part 1. Historical background; carbon tetrachloride and tetrachloroethylene. J Environ Forensics1:69–81</ref>. They also have been used in a wide variety of other purposes such as adhesives, chemical intermediates, clothes, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and textile processing.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==PHYSICAL and CHEMICAL PROPERTIES==

| |

| − | | |

| − | Chlorinated solvents are organic compounds generally constructed of a simple hydrocarbon chain (typically one to three carbon atoms in length). They can be divided into three categories based on their structural characteristics: chlorinated methanes, chlorinated ethanes and chlorinated ethenes.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Chlorinated methanes represent the most structurally simple solvent class and consist of a single carbon center (known as a methyl carbon) to which as many as four chlorine atoms are bonded. From the perspective of groundwater contamination, perhaps the most well-known chlorinated methanes are [[wikipedia:carbon tetrachloride|carbon tetrachloride (CT)]] or [[wikipedia:tetrachloromethane|tetrachloromethane]], [[wikipedia:trichloromethane|trichloromethane]] (commonly known as [[wikipedia:chloroform|chloroform [CF])]], [[wikipedia:dichloromethane|dichloromethane (DCM)]], or [[wikipedia:methylene chloride|methylene chloride (MC)]] and [[wikipedia:chloromethane|chloromethane (CM)]], or [[wikipedia:methyl chloride|methyl chloride]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | Chlorinated ethanes consist of two carbon centers joined by a single covalent bond. The most frequently encountered groundwater pollutants of this class include [[wikipedia:1,1,1-trichloroethane|1,1,1-trichloroethane (1,1,1-TCA)]] and [[wikipedia:1,2-dichloroethane|1,2-dichloroethane]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | Chlorinated ethenes (also referred to as chlorinated ethylenes) also possess two carbon centers, but unlike chlorinated ethanes, these carbon atoms are joined by a carbon-carbon double bond. Chlorinated ethenes that are important groundwater contaminants include [[wikipedia:tetrachloroethene|tetrachloroethene]], or [[wikipedia:perchloroethene|perchloroethene (PCE)]], [[wikipedia:trichloroethene|trichloroethene (TCE)]], [[wikipedia:dichloroethene|dichloroethene (DCE)]]) (DCE, mainly two geometric isomers cis-1,2-dichloroethene and trans-1,2-dichloroethene), and [[wikipedia:vinyl chloride|vinyl chloride (VC)]]. Nomenclature and structure of selected compounds from each solvent class are shown in Table 1.

| |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right: 40px; color:black; background-color:white; width: 60%;"

| |

| − | |+Table 1. Nomenclature and Structure of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents <ref name="CS 2010">Cwiertny, D. M. and M.M. Scherer, 2010. Chapter 2, Chlorinated Solvent Chemistry: Structures, Nomenclature and Properties. In: HF Stroo and CH.Ward (eds.). In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. Springer, pp. 29-37. ISBN: 978-0-387-23036-8/e-ISBN: 978-0-387-23079-5, DOI: 10.1007/0-387-23079-3_32</ref>

| |

| − | |- style="color:white; background-color:#006699; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | | IUPAC Name

| |

| − | | Common Name

| |

| − | | Abbreviation/Acronym

| |

| − | | CAS Registry Number

| |

| − | | Molecular Formula

| |

| − | | Chemical Structure

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="6" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Methanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|carbon tetrachloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| CT

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| 56-23-5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CCl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Tetrachloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|chloroform

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CF

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| 67-66-3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CHCl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trichloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|dichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methylene chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|DCM

| |

| − | | style="text-alighn:center;"|75-09-2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CH<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Dichloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methyl chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CM

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|74-87-3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CH<sub>3</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloromethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="6" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|hexachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|perchloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|HCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|67-72-1

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>6</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:hexachloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|pentachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|PCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|76-01-7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>HCl<sub>5</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:pentachloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,1,2-TeCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|630-20-6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,1,2-Tetrachloroethane.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,2,2-TeCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|79-34-5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,2-TCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|79-00-5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,2-Trichloroethane.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|methyl chloroform

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1,1-TCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|71-55-6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1,1-trichloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,2-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,2-DCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|107-06-2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,2-dichloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1-DCA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|75-34-3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1-Dichloroethane 2.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|CA

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|75-00-3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>5</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloroethane.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="6" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethenes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|perchloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|PCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center:"|127-18-4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>4</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Tetrachloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|TCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|79-01-6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>HCl<sub>3</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trichloroethene.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>cis</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>cis</i>-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>cis</i>-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|156-59-2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Cis-1,2-dichloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>trans</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>trans</i>-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|<i>trans</i>-DCE

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|156-60-5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Trans-1,2-dichloroethene.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|vinylidene chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,1-DCE

| |

| − | | style+"text-alighn:center;"|75-35-4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:1,1-Dichloroethene.svg.png|72px|frameless|center]]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|vinyl chloride

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|VC

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|75-01-4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Cl

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | [[File:Chloroethene.png|center|70px|frameless]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The chlorinated solvents and many of their transformation products are colorless liquids at room temperature. They are heavier than water with densities greater than 1 gram per cubic centimeter (g/cm<sub>3</sub>) which means they can penetrate deeply into an aquifer. Some physical and chemical properties of most widely used chlorinated solvents are listed in Table 2.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right: 40px; color:black; background-color:white; width: 60%;"

| |

| − | |+Table 2. Physical and Chemical Properties of Most Widely Used Chlorinated Solvents at 25°C. Unless otherwise noted, all values have been taken from Mackay et al. (1993) <ref name="CS 2010">Cwiertny, D. M. and M.M. Scherer, 2010. Chapter 2, Chlorinated Solvent Chemistry: Structures, Nomenclature and Properties. In: HF Stroo and CH.Ward (eds.). In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. Springer, pp. 29-37. ISBN: 978-0-387-23036-8/e-ISBN: 978-0-387-23079-5, DOI: 10.1007/0-387-23079-3_32</ref>

| |

| − | |- style="color:white; background-color:#006699; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | | Species

| |

| − | | Formula Weight

| |

| − | | Carbon Oxidation State<sup>a</sup>

| |

| − | | Density (ρ)(g/mL)

| |

| − | | Solubility (mg/L)

| |

| − | | Vapor Pressure (ρ<sup>0</sup>)(kPa)

| |

| − | | Henry's Law Constant (K<sub>H</sub>)(x10<sup>-3</sup>

| |

| − | | Log K<sub>ow</sub>

| |

| − | | Log K<sub>oc</sub><sup>b</sup>

| |

| − | | MCL<sup>c</sup> (μg/L)

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="10" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Methanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|153.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+IV

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.59

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|800

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|20.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|28.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.64

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|119.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+III

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.97

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.52

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.080<sup>d</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|dichloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|84.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+II

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.33

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|13,200

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|55.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloromethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+I

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,235

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|570

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.91

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR<sup>e</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="10" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethanes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|hexachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|236.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+III

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.09

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|50

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.05<sup>f</sup>

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.93

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|pentachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|202.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+III

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.68

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|500

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.89

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+I

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.54

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.6

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|167.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+I

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.60

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2,962

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.39

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,2-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.44

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,394

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|3.22

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.96

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.38

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1,1-trichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|133.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.35

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,495

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|14.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.49

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.20

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,2-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-I

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.25

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|8,606

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|10.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.48

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.52

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|1,1-dichloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|99.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-I

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.17

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|4,676

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|30.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|6.2

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.79

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|chloroethane

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|64.5

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-II

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.92

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|5,700

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|16.0

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.43

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|-

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|NR

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="10" style="color:black; background-color:#99C2D6;"|Chlorinated Ethenes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|tetrachloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|165.8

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+II

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.63

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|150

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|26.3

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.88

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.29

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|trichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|131.4

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|+I

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.46

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1,100

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|9.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|11.7

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|2.53

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|1.53

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0.005

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="color:black; background-color:#E6F0F5;"|<i>cis</i>-1,2-dichloroethene

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|96.9

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"|0

| |