User:Debra Tabron/sandbox

Passive sampling using integrative samplers enables the monitoring of munitions constituents in underwater environments over timescales of days to months and at ultra-low concentrations. Munitions compounds have an affinity for some resins and polymers that, when submerged for a period of time and corrected for the environment-specific sampling rate, can be used to determine time weighted average ambient water concentrations. This article primarily details the Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler (POCIS), its optimization using laboratory flume and field experiments, and its application at munitions-impacted underwater sites.

Related Article(s):

CONTRIBUTOR(S): Dr. Guilherme Lotufo and Gunther Rosen

Key Resource(s):

- Validation of Passive Sampling Devices for Monitoring of Munitions Constituents in Underwater Environments[1].

Background

Underwater unexploded ordnance (UXO) at active and former training ranges and discarded military munitions (DMM), collectively referred to as underwater munitions and explosives of concern (MEC), present challenges due to both immediate safety considerations (e.g. explosive blast) and potential ecological and human health impacts resulting from the release of munition constituents (MC) to the marine environment. Underwater sites around the world are known to contain MEC as a result of military activities or historic disposal events (Figure 1). MC including 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) and 1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) may be released into the surrounding aquatic environments as a result of MEC corrosion and breaching of the munition’s outer casing[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]. Release may also occur from fragments of explosives formulations that become exposed following low-order (incomplete) detonations (LOD) resulting in fully breached munitions[9] (Figure 2).

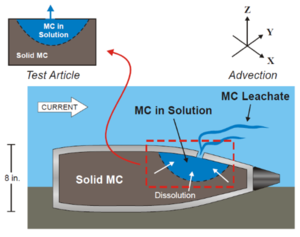

The rate of release of MC from MEC into the surrounding environment is expected to be influenced by the size of the initial breach and growth of the breach hole in the munition casing, the radius of the cavity formed due to loss of MC mass from inside the MEC, the dissolution rate from solid to aqueous phases of the MC inside the MEC, the outside ambient current to which the casing breach hole is exposed, and the mass of MC remaining inside[4][10]. Subsequent to the breaching event, concentrations in the surrounding environment are expected to fluctuate over time because of the dependence of release kinetics on the above parameters, as well as hydrodynamic conditions leading to dilution effects, sorption to suspended particles, photo-transformation, and other factors leading to MC loss from the aquatic environment[6][11][12]. As a result of slow release and rapid removal of MC in the surrounding water[8][11][12], MC have been detected at low frequency relative to the number of samples examined and at low concentrations at Underwater Military Munitions (UWMM) sites[6][8][11]. Overall, munitions constituent persistence in the environment is a key determinant of exposure[11]. Exposure to MC in water has been shown to be toxic to aquatic organisms belonging to various taxonomic groups[8][11][13][14].

Underwater Sampling Challenges

Considering that MC are expected to be present at UWMM sites mainly at ultra-low concentrations and with concentrations decreasing with increasing distance from the source of released MC[7][15][16][1], a number of challenges prevent accurate assessment of environmental exposure using traditional water, sediment, and tissue sampling and analyses. These challenges include a high level of effort or difficulty required to:

1. identify breached underwater MEC that are actually releasing MC;

2. measure MC in the water column at low levels; and

3. characterize water column exposure using the appropriate spatial and temporal scales for determining ecological risk.

Standard environmental sampling, such as grab sampling of surface water, only generates information for the time of sample collection, and spot grab sampling strategies may inadequately capture temporal changes[17] in MC concentrations that occur at UWMM sites, thereby providing an inaccurate measure of environmental exposure. In contrast, integrative passive sampling has been used to derive ultra-low and time-weighted water concentrations for a wide range of environmental contaminants[18], including MC[7][19][20][21][22][23]. Polar organic chemical integrative samplers (POCIS)[24] currently are the most widely used samplers for weakly hydrophobic contaminants (typically those with log Kow < 4).

The US Department of Defense’s Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) provided funding for research aimed at optimizing use of POCIS passive sampling technology for sampling MC in water and at demonstrating the application of POCIS to determine time-weighted average (TWA) water-column concentrations in the vicinity of MEC at a UWMM site (ESTCP Project ER‐201433)[1]. Some results of that project are presented in the following sections of this article.

Technology Overview

The POCIS consists of a receiving phase (sorbent) sandwiched between two polyethersulfone (PES) microporous membranes with ~0.1 μm pore size[24] (Figure 3). The sampler is held together by two stainless steel rings with an interior diameter of 51-54 mm, which provides an exposure surface area of 41-46 cm2. The POCIS are available commercially from Environmental Sampling Technologies (EST; St. Joseph, Missouri), and contain the widely used Oasis® hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) polymer as the sorbent. A variety of sampler holders and canisters have been used to protect the passive samplers in the field. The holder and canister shown in Figure 4 are commercially available from EST.

For passive sampling of contaminants, the POCIS are kept immersed in water typically for two weeks to one month. However, depending on the study objectives, deployment times can range from days to months. At the end of the deployment time the POCIS are collected and transported to a laboratory where they are dismantled for collection of the full mass of sorbent. Analytes are extracted from sorbent using standard techniques, typically by organic solvent extraction in a chromatography column. The eluate can be analyzed using instrumental techniques such as liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC/MS) or by gas chromatography coupled with MS (GC/MS). More than 300 chemicals with a wide range of commercial and industrial applications have been detected or quantified by the POCIS in laboratory and field testing[25].

Accumulation in the POCIS is based on passive diffusion of analytes from water into the POCIS receiving phase. The POCIS is designed to operate as an infinite sink for analytes during the linear uptake stage. As such, it is used to determine TWA concentrations but does not capture any fluctuations in concentrations that occur during the deployment period. In order to obtain TWA concentrations of the molecules being studied, laboratory or in situ calibration of the POCIS is necessary. The calibration allows the determination of chemical-specific sampling rates (Rs) using experimentally derived uptake rates. The Rs is defined as the volume of water cleared in a unit of time (typically L/d). The sampling rates are necessary to convert the mass of a compound accumulated in the sorbent phase of the sampler to its concentration in the environmental medium sampled. Sampling rates are typically empirically derived during laboratory studies employing a closed system in which the contaminants of concern are spiked only at the beginning of the experiment or at constant time intervals[19][27][28]. The POCIS-derived TWA is calculated using Equation 1:

| Equation 1: | Cw = N / (Rs* t) | |

| Where: | ||

| Cw | is the TWA water concentration (ng/L), | |

| N | is the mass of the chemical accumulated by the sampler (ng), | |

| Rs | is the sampling rate (L/day), and | |

| t | is the exposure time (days). |

A multitude of factors affect the sampling rate. The pattern and rate of water flow (i.e., current’s velocity and direction) across the PES membranes that house the POCIS sorbent generally have the largest impact on Rs. This is because diffusion of dissolved substances across the membrane is dependent on the thickness of the water boundary layer at the membrane surface, which is affected by water flow induced turbulence around the sampler[29][30]. Other variables such as biofouling have also been found to have some impact on Rs[31]. The accuracy of calibrated sampling rates for subsequent environmental studies is dependent on how similar the site exposure conditions are to those used in the calibration experiment[29]. Therefore, samplers should be calibrated in conditions as close as possible to those expected at the monitored sites[23].

Because of the wide range of field environmental conditions, the biggest challenge facing the use of POCIS has been the lack of a correction method to quantify the effect on the uptake process when field conditions vary from those of the calibration experiment. To overcome this issue, performance reference compounds (PRCs) with experimentally quantified dissipation rates can be spiked into the samplers prior to deployment to account for the effects of field exposure conditions on RS values. PRCs should be chosen that do not occur in the environment in which the sampler will be used. The selected PRC should also be significantly but not completely depleted over the planned deployment period. The mass of PRC lost during deployment is then used to improve the accuracy of the estimated TWA concentration of the analyte of interest. Performance reference compounds have been successfully and widely used to correct for the impact of exposure conditions on hydrophobic passive samplers[32]. A study by Li et al.[33] was the first to demonstrate the reliable use of PRCs for determining TWA concentrations in the field using POCIS.

POCIS typically exhibit negligible analyte loss rates even when local environmental concentrations of the analyte drop to undetectable levels for some portion of the deployment period. This allows small masses of a chemical of interest from episodic release events to be retained in the device at the end of the deployment period[19][34][35][36]. Therefore, the POCIS offer an advantageous alternative to traditional sampling methods (e.g. collection of discrete grab samples) at sites where fluctuation in concentrations or low-level concentrations are expected to occur, such as in the vicinity of underwater munitions. The continuous sampling approach of POCIS allows quantification of concentrations in an integrative manner as time weighted averages that are representative of the entire sampling period. The cumulative sampling of contaminant mass over the sampling period also enriches the analyte in the sorbent, which improves detection and quantification of the analyte. As another advantage, the POCIS provides protection of sorbed analytes against decomposition during post-deployment transport and storage[37].

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Rosen, G., Colvin, M., George, R., Lotufu, G., Woodley, C., Smith, D. and Belden, J., 2017. Validation of passive sampling devices for monitoring of munitions constituents in underwater environments (No. SPAWAR-SCP-TR-3076). SPAWAR Systems Center Pacific San Diego. Report.pdf

- ^ Lewis, J., Martel, R., Trépanier, L., Ampleman, G. and Thiboutot, S., 2009. Quantifying the transport of energetic materials in unsaturated sediments from cracked unexploded ordnance. Journal of environmental quality, 38(6), pp.2229-2236. doi: 10.2134/jeq2009.0019 Free pdf download

- ^ Rosen, G. and Lotufo, G.R., 2010. Fate and effects of Composition B in multispecies marine exposures. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 29(6), pp.1330-1337.Report.pdf

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Wang, P.F., Liao, Q., George, R. and Wild, W., 2011. Release rate and transport of munitions constituents from breached shells in marine environment. In Environmental chemistry of explosives and propellant compounds in soils and marine systems: Distributed source characterization and remedial technologies (pp. 317-340). American Chemical Society. doi: 10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch016

- ^ Li, Y., Yang, C., Bao, Y., Ma, X., Lu, G. and Li, Y., 2016. Aquatic passive sampling of perfluorinated chemicals with polar organic chemical integrative sampler and environmental factors affecting sampling rate. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(16), pp.16096-16103. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6791-1

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Voie, Øyvind A., and Espen Mariussen. "Risk assessment of sea dumped conventional munitions." Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics 42, no. 1 (2017): 98-105. doi:10.1002/prep.20160

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rosen, G., Lotufo, G.R., George, R.D., Wild, B., Rabalais, L.K., Morrison, S. and Belden, J.B., 2018. Field validation of POCIS for monitoring at underwater munitions sites. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 37(8), pp.2257-2267. doi: 10.1002/etc.4159

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Beck, A.J., Gledhill, M., Schlosser, C., Stamer, B., Böttcher, C., Sternheim, J., Greinert, J. and Achterberg, E.P., 2018. Spread, behavior, and ecosystem consequences of conventional munitions compounds in coastal marine waters. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5, p.141. Report.pdf

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Beck, A.J., van der Lee, E.M., Eggert, A., Stamer, B., Gledhill, M., Schlosser, C. and Achterberg, E.P., 2019. In situ measurements of explosive compound dissolution fluxes from exposed munition material in the Baltic Sea. Environmental science & technology, 53(10), pp.5652-5660. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06974

- ^ Wang, P. F., George, R. D., Wild, W. J., and Liao, Q., 2013. Defining munition constituent (MC) source terms in aquatic environments on DoD Ranges (ER-1453), Final Report. SSC Pacific Technical Report 1999. Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center (SSC) Pacific: San Diego, CA Report.pdf

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Lotufo, G.R., Chappell, M.A., Price, C.L., Ballentine, M.L., Fuentes, A.A., Bridges, T.S., George, R.D., Glisch, E.J., Carton, G. 2017. Review and synthesis of evidence regarding environmental risks posed by munitions constituents (MC) in aquatic systems, Final report. SERDP Project ER-2341. ERDC/EL TR-17-17. US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, Vicksburg, MS Report.pdf

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Tobias, C. 2019. Tracking the uptake, translocation, cycling, and metabolism of munitions compounds in coastal marine ecosystems using Stable Isotopic Tracer, Final Report. SERDP Project ER-2122. Report.pdf

- ^ Craig, H.D. and Taylor, S., 2011. Framework for evaluating the fate, transport, and risks from conventional munitions compounds in underwater environments. Marine Technology Society Journal, 45(6), pp.35-46. doi: 10.4031/MTSJ.45.6.10

- ^ Lotufo, G.R., Rosen, G., Wild, W. and Carton, G., 2013. Summary review of the aquatic toxicology of munitions constituents (No. ERDC/EL-TR-13-8). US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, Vicksburg, MS Report.pdf

- ^ Rodacy, P.J., Reber, S.D., Walker, P.K. and Andre, J.V., 2001. Chemical sensing of explosive targets in the Bedford Basin, Halifax Nova Scotia. Sandia National Laboratories. Report.pdf

- ^ Porter, J.W., Barton, J.V. and Torres, C., 2011. Ecological, radiological, and toxicological effects of naval bombardment on the coral reefs of Isla de Vieques, Puerto Rico. In Warfare Ecology (pp. 65-122). Springer, Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1214-0_8

- ^ Poulier, G., Lissalde, S., Charriau, A., Buzier, R., Cleries, K., Delmas, F., Mazzella, N. and Guibaud, G., 2015. Estimates of pesticide concentrations and fluxes in two rivers of an extensive French multi-agricultural watershed: application of the passive sampling strategy. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(11), pp.8044-8057.

- ^ Roll, I.B. and Halden, R.U., 2016. Critical review of factors governing data quality of integrative samplers employed in environmental water monitoring. Water research, 94, pp.200-207. Open Access Manuscript

- ^ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Belden, J.B., Lotufo, G.R., Biedenbach, J.M., Sieve, K.K. and Rosen, G., 2015. Application of POCIS for exposure assessment of munitions constituents during constant and fluctuating exposure. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 34(5), pp.959-967. doi: 10.1002/etc.2836

- ^ Rosen, G., Wild, B., George, R.D., Belden, J.B. and Lotufo, G.R., 2016. Optimization and field demonstration of a passive sampling technology for monitoring conventional munition constituents in aquatic environments. Marine Technology Society Journal, 50(6), pp.23-32. doi: 10.4031/MTSJ.50.6.4

- ^ Lotufo, G.R., George, R.D., Belden, J.B., Woodley, C.M., Smith, D.L. and Rosen, G., 2018. Investigation of polar organic chemical integrative sampler (POCIS) flow rate dependence for munition constituents in underwater environments. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 190(3), p.171. doi: 10.1007/s10661-018-6558-x

- ^ Lotufo, G.R., George, R.D., Belden, J.B., Woodley, C., Smith, D.L. and Rosen, G., 2019. Release of Munitions Constituents in Aquatic Environments Under Realistic Scenarios and Validation of Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Samplers for Monitoring. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 38(11), pp.2383-2391. doi: 10.1002/etc.4553

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Estoppey, N., Mathieu, J., Diez, E.G., Sapin, E., Delémont, O., Esseiva, P., de Alencastro, L.F., Coudret, S. and Folly, P., 2019. Monitoring of explosive residues in lake-bottom water using Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler (POCIS) and chemcatcher: determination of transfer kinetics through Polyethersulfone (PES) membrane is crucial. Environmental pollution, 252, pp.767-776. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.087

- ^ 24.0 24.1 Alvarez, D.A., Petty, J.D., Huckins, J.N., Jones‐Lepp, T.L., Getting, D.T., Goddard, J.P. and Manahan, S.E., 2004. Development of a passive, in situ, integrative sampler for hydrophilic organic contaminants in aquatic environments. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry: An International Journal, 23(7), pp.1640-1648. doi:10.1897/03-603

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Morin, N., Miège, C., Coquery, M. and Randon, J., 2012. Chemical calibration, performance, validation and applications of the polar organic chemical integrative sampler (POCIS) in aquatic environments. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 36, pp.144-175. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2012.01.007 Author's Manuscript

- ^ Seethapathy, S., Gorecki, T. and Li, X., 2008. Passive sampling in environmental analysis. Journal of Chromatography A, 1184(1-2), pp.234-253. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.07.070

- ^ Mazzella, N., Dubernet, J.F. and Delmas, F., 2007. Determination of kinetic and equilibrium regimes in the operation of polar organic chemical integrative samplers: Application to the passive sampling of the polar herbicides in aquatic environments. Journal of Chromatography A, 1154(1-2), pp.42-51. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.03.087

- ^ Arditsoglou, A. and Voutsa, D., 2008. Passive sampling of selected endocrine disrupting compounds using polar organic chemical integrative samplers. Environmental Pollution, 156(2), pp.316-324. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.02.007

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Harman, C., Allan, I.J. and Vermeirssen, E.L., 2012. Calibration and use of the polar organic chemical integrative sampler-a critical review. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 31(12), pp.2724-2738. doi: 10.1002/etc.2011 Report.pdf

- ^ Godlewska, K., Stepnowski, P. and Paszkiewicz, M., 2020. Application of the Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler for Isolation of Environmental Micropollutants–A Review. Critical reviews in Analytical Chemistry, 50(1), pp.1-28. doi: 10.1080/10408347.2019.1565983

- ^ Li, Y., Yang, C., Zha, D., Wang, L., Lu, G., Sun, Q. and Wu, D., 2018. In situ calibration of polar organic chemical integrative samplers to monitor organophosphate flame retardants in river water using polyethersulfone membranes with performance reference compounds. Science of The Total Environment, 610, pp.1356-1363. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.234

- ^ Booij, K. and Smedes, F., 2010. An improved method for estimating in situ sampling rates of nonpolar passive samplers. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(17), pp.6789-6794. doi: 10.1021/es101321v

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLi2018 - ^ Harman, C., Thomas, K.V., Tollefsen, K.E., Meier, S., Bøyum, O. and Grung, M., 2009. Monitoring the freely dissolved concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and alkylphenols (AP) around a Norwegian oil platform by holistic passive sampling. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58(11), pp.1671-1679. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.06.022

- ^ Morrison, S.A. and Belden, J.B., 2016. Calibration of nylon organic chemical integrative samplers and sentinel samplers for quantitative measurement of pulsed aquatic exposures. Journal of Chromatography A, 1449, pp.109-117. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.04.072

- ^ Bernard, M., Boutry, S., Tapie, N., Budzinski, H. and Mazzella, N., 2018. Lab-scale investigation of the ability of Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler to catch short pesticide contamination peaks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, pp.1-11. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3391-2

- ^ Miège, C., Mazzella, N., Allan, I., Dulio, V., Smedes, F., Tixier, C., Vermeirssen, E., Brant, J., O’Toole, S., Budzinski, H. and Ghestem, J.P., 2015. Position paper on passive sampling techniques for the monitoring of contaminants in the aquatic environment–achievements to date and perspectives. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 8, pp.20-26. Author's Manuscript