Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Selection of Flushing Agent) |

|||

| (730 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | ==Transition of Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) Fire Suppression Infrastructure Impacted by Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)== | |

| − | + | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)|Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)]] contained in [[wikipedia:Firefighting foam |Class B aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs)]] are known to accumulate on wetted surfaces of many fire suppression systems after decades of exposure<ref name="LangEtAl2022">Lang, J.R., McDonough, J., Guillette, T.C., Storch, P., Anderson, J., Liles, D., Prigge, R., Miles, J.A.L., Divine, C., 2022. Characterization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on fire suppression system piping and optimization of removal methods. Chemosphere, 308(Part 2), 136254. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136254 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136254] [[Media:LangEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. When replacement PFAS-free firefighting formulations are added to existing infrastructure, PFAS can rebound from the wetted surfaces into the new formulations at high concentrations<ref name="RossStorch2020">Ross, I., and Storch, P., 2020. Foam Transition: Is It as Simple as "Foam Out / Foam In?". The Catalyst (Journal of JOIFF, The International Organization for Industrial Emergency Services Management), Q2 Supplement, 20 pages. [[Media:Catalyst_2020_Q2_Sup.pdf | Industry Newsletter]]</ref><ref>Kappetijn, K., 2023. Replacement of fluorinated extinguishing foam: When is clean clean enough? The Catalyst (Journal of JOIFF, The International Organization for Industrial Emergency Services Management), Q1 2023, pp. 31-33. [[Media:Catalyst_2023_Q1.pdf | Industry Newsletter]]</ref>. Effective methods are needed to properly transition to PFAS-free firefighting formulations in existing fire suppression infrastructure. Considerations in the transition process may include but are not limited to locating, identifying, and evaluating existing systems and AFFF, fire engineering evaluations, system prioritization, cost/downtime analyses, sampling and analysis, evaluation of risks and hazards to human health and the environment, transportation, and disposal. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

| − | '''Related Article(s)''' | + | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| − | + | *[[PFAS Sources]] | |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] |

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''Contributor(s):''' |

| + | *Dr. Johnsie Ray Lang | ||

| + | *Dr. Jonathan Miles | ||

| + | *John Anderson | ||

| + | *Dr. Theresa Guillette | ||

| + | *[[Craig E. Divine, Ph.D., PG|Dr. Craig Divine]] | ||

| + | *[[Dr. Stephen Richardson]] | ||

'''Key Resource(s):''' | '''Key Resource(s):''' | ||

| − | * | + | *Department of Defense (DoD) performance standard for PFAS-free firefighting formulation: [https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jan/12/2003144157/-1/-1/1/MILITARY-SPECIFICATION-FOR-FIRE-EXTINGUISHING-AGENT-FLUORINE-FREE-FOAM-F3-LIQUID-CONCENTRATE-FOR-LAND-BASED-FRESH-WATER-APPLICATIONS.PDF Military Specification MIL-PRF-32725]<ref name="DoD2023">US Department of Defense, 2023. Performance Specification for Fire Extinguishing Agent, Fluorine-Free Foam (F3) Liquid Concentrate for Land-Based, Fresh Water Applications. Mil-Spec MIL-PRF-32725, 18 pages. [[Media: MilSpec32725.pdf | Military Specification Document]]</ref> |

| − | + | *[[Media:LangEtAl2022.pdf | Characterization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on fire suppression system piping and optimization of removal methods]]<ref name="LangEtAl2022"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Introduction== | |

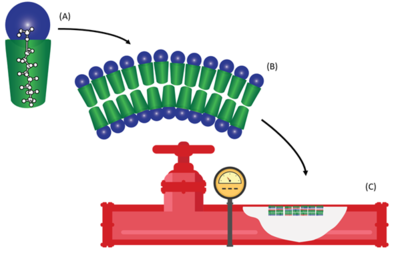

| − | [ | + | [[File:LangFig1.png | thumb |400px|Figure 1. (A) Schematic of a typical PFAS molecule demonstrating the hydrophobic fluorinated tail in green and the hydrophilic charged functional group in blue, (B) a PFAS bilayer formed with the hydrophobic tails facing inward and the charged functional groups on the outside, and (C) multiple bilayers of PFAS assembled on the wetted surfaces of fire suppression piping.]]PFAS are a class of synthetic fluorinated compounds which are highly mobile and persistent within the environment<ref>Giesy, J.P., Kannan, K., 2001. Global Distribution of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Wildlife. Environmental Science and Technology 35(7), pp. 1339-1342. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es001834k doi: 10.1021/es001834k]</ref>. Due to the surfactant properties of PFAS, these compounds self-assemble at any solid-liquid interface forming resilient bilayers during prolonged exposure<ref>Krafft, M.P., Riess, J.G., 2015. Selected physicochemical aspects of poly- and perfluoroalkylated substances relevant to performance, environment and sustainability-Part one. Chemosphere, 129, pp. 4-19. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.039 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.039]</ref>. Solid phase accumulation of PFAS has been proposed to be influenced by both [[wikipedia: Hydrophobic effect|hydrophobic]] and electrostatic interactions with fluorinated carbon chain length as the dominant feature influencing sorption<ref>Higgins, C.P., Luthy, R.G., 2006. Sorption of Perfluorinated Surfactants on Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(23), pp. 7251-7256. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es061000n doi: 10.1021/es061000n]</ref>. While the majority of previous research into solid phase sorption typically focused on water treatment applications or subsurface porous media<ref>Brusseau, M.L., 2018. Assessing the Potential Contributions of Additional Retention Processes to PFAS Retardation in the Subsurface. Science of the Total Environment, 613-614, pp. 176-185. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.065 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.065] [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5693257/ Open Access Manuscript]</ref>, recently PFAS accumulations have been identified on the wetted surfaces of fire suppression infrastructure exposed to aqueous film forming foam (AFFF)<ref name="LangEtAl2022"/> (see Figure 1). |

| − | [[File: | + | |

| + | Fire suppression systems with potential PFAS impacts include fire fighting vehicles that carried AFFF and fixed suppression systems in buildings containing large amounts of flammable materials such as aircraft hangars (Figure 2). PFAS residue on the wetted surfaces of existing infrastructure can rebound into replacement PFAS-free firefighting formulations if not removed during the transition process<ref name="RossStorch2020"/>. Simple surface rinsing with water and low-pressure washing has been proven to be inefficient for removal of surface bound PFAS from piping and tanks that contained fluorinated AFFF<ref name="RossStorch2020"/> | ||

| + | [[File:LangFig2.png | thumb|left|600px|Figure 2. Fixed fire suppression system for an aircraft hangar, with storage tank on left and distribution piping on right.]] | ||

| − | + | In addition to proper methods for system cleaning to remove residual PFAS, transition to PFAS-free foam may also include consideration of compliance with state and federal regulations, selection of the replacement PFAS-free firefighting formulation, a cost benefit analysis for replacement of the system components versus cleaning, and PFAS verification testing. Foam transition should be completed in a manner which minimizes the volume of waste generated as well as preventing any PFAS release into the environment. | |

| − | + | ==PFAS Assembly on Solid Surfaces== | |

| + | The self-assembly of [[Wikipedia: Amphiphile | amphiphilic]] molecules into supramolecular bilayers is a result of their structure and how it interacts with the bulk water of a solution. Single chain hydrocarbon based amphiphiles can form [[Wikipedia: Micelle | micelles]] under relatively dilute aqueous concentrations, however for hydrocarbon based surfactants the formation of more complex organized system such as [[Wikipedia: Vesicle (biology and chemistry) | vesicles]] is rarely seen, requiring double chain amphiphiles such as [[wikipedia: Phospholipid|phospholipids]]. Associations of single chain [[wikipedia: Ion#Anions_and_cations|cationic and anionic]] hydrocarbon based amphiphiles into stable supramolecular structures such as vesicles has however been demonstrated<ref>Fukuda, H., Kawata, K., Okuda, H., 1990. Bilayer-Forming Ion-Pair Amphiphiles from Single-Chain Surfactants. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 112(4), pp. 1635-1637. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00160a057 doi: 10.1021/ja00160a057]</ref>, with the ion pairing of the polar head groups mimicking the a double tail situation. The behavior of single chain [[wikipedia: Per-_and_polyfluoroalkyl_substances#Fluorosurfactants|fluorosurfactant]] amphiphiles has been demonstrated to be significantly different from similar hydrocarbon based analogues. Not only are [[Wikipedia: Critical micelle concentration | critical micelle concentrations (CMC)]] of fluorosurfactants typically two orders of magnitude lower than corresponding hydrocarbon surfactants but self-assembly can occur even when fluorosurfactants are dispersed at low concentrations significantly below the CMC in water and other solvents<ref name="Krafft2006">Krafft, M.P., 2006. Highly fluorinated compounds induce phase separation in, and nanostructuration of liquid media. Possible impact on, and use in chemical reactivity control. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 44(14), pp. 4251-4258. [https://doi.org/10.1002/pola.21508 doi: 10.1002/pola.21508] [[Media:Krafft2006.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. The assembly of fluorinated amphiphiles structurally similar to those found in AFFF have been shown to readily form stable, complex structures including vesicles, fibers, and globules at concentrations as low as 0.5% w/v in contrast to their hydrocarbon analogues which remained fluid at 30% w/v<ref>Krafft, M.P., Guilieri, F., Riess, J.G., 1993. Can Single-Chain Perfluoroalkylated Amphiphiles Alone form Vesicles and Other Organized Supramolecular Systems? Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 32(5), pp. 741-743. [https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199307411 doi: 10.1002/anie.199307411]</ref><ref name="KrafftEtAl_1994">Krafft, M.P., Guilieri, F., Riess, J.G., 1994. Supramolecular assemblies from single chain perfluoroalkylated phosphorylated amphiphiles. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 84(1), pp. 113-119. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-7757(93)02681-4 doi: 10.1016/0927-7757(93)02681-4]</ref>. | ||

| − | = | + | Krafft found that fluorinated amphiphiles formed bilayer membranes with phospholipids, and that the resulting vesicles were more stable than those made of phospholipids alone<ref name="KrafftEtAl_1998">Krafft, M.P., Riess, J.G., 1998. Highly Fluorinated Amphiphiles and Collodial Systems, and their Applications in the Biomedical Field. A Contribution. Biochimie, 80(5-6), pp. 489-514. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9084(00)80016-4 doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(00)80016-4]</ref>. The similarities in amphiphilic properties between phospholipids and the hydrocarbon-based surfactants in AFFF suggests that bilayer vesicles may form between these and the fluorosurfactants also present in the concentrate. Krafft demonstrated that both the permeability of resulting mixed vesicles and their propensity to fuse with each other at increasing ionic strength was reduced as a result of the creation of an inert hydrophobic and [[wikipedia: Lipophobicity|lipophobic]] film within the membrane, and also suggested that the fluorinated amphiphiles increased [[Wikipedia: van der Waals force | van der Waals interactions]] in the hydrocarbon region<ref name="KrafftEtAl_1998"/>. Thus this low permeability may allow vesicles formed by the surfactants present in AFFF to act as long term repositories of PFAS not only as part of the bilayer itself but also solvated within the vesicle. This prediction is supported by the observation that supramolecular structures formed from single chain fluorinated amphiphiles have been demonstrated to be stable at elevated temperature (15 min at 121°C) and have been shown to be stable over periods of months, even increasing in size over time when stored at environmentally relevant temperatures<ref name="KrafftEtAl_1994"/>. |

| − | |||

| − | < | + | Formation of complex structures at relatively low solute concentrations requires the monomer molecules to be well ordered to maintain tight packing in the supramolecular structure<ref>Ringsdorf, H., Schlarb, B., Venzmer, J., 1988. Molecular Architecture and Function of Polymeric Oriented Systems: Models for the Study of Organization, Surface Recognition, and Dynamics of Biomembranes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 27(1), pp. 113-158. [https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.198801131 doi: 10.1002/anie.198801131]</ref>. This order results from electrostatic forces, [[wikipedia: Hydrogen bond|hydrogen bonding]], and in the case of fluorinated amphiphiles, hydrophobic interactions. The geometry of the amphiphile also potentially contributes to the type of supramolecular aggregation<ref>Israelachvili, J.N., Mitchell, D.J., Ninham, B.W., 1976. Theory of Self-Assembly of Hydrocarbon Amphiphiles into Micelles and Bilayers. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 2: Molecular and Chemical Physics, 72, pp. 1525-1568. [https://doi.org/10.1039/F29767201525 doi: 10.1039/F29767201525]</ref>. Surfactants which adopt a conical shape (such as a typical hydrocarbon based surfactant with a large polar head group and a single alkyl chain as a tail) tend to form micelles more easily. Increasing the bulk of the tail makes the surfactant more cylindrically shaped which makes assembly into bilayers more likely. |

| − | + | Perfluoroalkyl chains are significantly more bulky than their hydrocarbon based analogues both in cross sectional area (28-30 Å<sup>2</sup> versus 20 Å<sup>2</sup>, respectively) and mean volume (CF<sub>2</sub> and CF<sub>3</sub> estimated as 38 Å<sup>3</sup> and 92 Å<sup>3</sup> compared to 27 Å<sup>3</sup> and 54 Å<sup>3</sup> for CH<sub>2</sub> and CH<sub>3</sub>)<ref name="KrafftEtAl_1998"/><ref name="Krafft2006"/>. Structural studies on linear PFOS have shown that the molecule adopts an unusual helical structure<ref>Erkoç, Ş., Erkoç, F., 2001. Structural and electronic properties of PFOS and LiPFOS. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM, 549(3), pp. 289-293. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-1280(01)00553-X doi:10.1016/S0166-1280(01)00553-X]</ref><ref name="TorresEtAl2009">Torres, F.J., Ochoa-Herrera, V., Blowers, P., Sierra-Alvarez, R., 2009. Ab initio study of the structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and its branched isomers. Chemosphere 76(8), pp. 1143-1149. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.04.009 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.04.009]</ref> in aqueous and solvent phases to alleviate [[wikipedia: Steric_effects#Steric_hindrance|steric hindrance]]. This arrangement results from the carbon chain starting in the planar all anti [[wikipedia:Conformational isomerism|conformation]] and then successively twisting all the CC-CC dihedrals by 15°-20° in the same direction<ref>Abbandonato, G., Catalano, D., Marini, A., 2010. Aggregation of Perfluoroctanoate Salts Studied by <sup>19</sup>F NMR and DFT Calculations: Counterion Complexation, Poly(ethylene glycol) Addition, and Conformational Effects. Langmuir 26(22), pp. 16762-16770. [https://doi.org/10.1021/la102578k doi: 10.1021/la102578k].</ref>. The conformation also minimizes the electrostatic repulsion between fluorine atoms bonded to the same side of the carbon backbone by maximizing the interatomic distances between them<ref name="TorresEtAl2009"/>. | |

| − | + | A consequence of the helical structure is that there is limited carbon-carbon bond rotation within the perfluoroalkyl chain giving them increased rigidity compared to alkyl chains<ref>Barton, S.W., Goudot, A., Bouloussa, O., Rondelez, F., Lin, B., Novak, F., Acero, A., Rice, S., 1992. Structural transitions in a monolayer of fluorinated amphiphile molecules. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 96(2), pp. 1343-1351. [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.462170 doi: 10.1063/1.462170]</ref>. The bulkiness of the perfluoroalkyl chain confers a cylindrical shape on the fluorosurfactant amphiphile and therefore favors the formation of bilayers and vesicles the aggregation of which is further assisted by the rigidity of the molecules which allow close packing in the supramolecular structure. Fluorosurfactants therefore cannot be regarded as more hydrophobic analogues of hydrogenated surfactants. Their self-assembly behavior is characterized by a strong tendency to form vesicles and lamellar phases rather than micelles, due to the bulkiness and rigidity of the perfluoroalkyl chain that tends to decrease the curvature of the aggregates they form in solution<ref>Barton, C.A., Butler, L.E., Zarzecki, C.J., Flaherty, J., Kaiser, M., 2006. Characterizing Perfluorooctanoate in Ambient Air near the Fence Line of a Manufacturing Facility: Comparing Modeled and Monitored Values. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, 56, pp. 48-55. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2006.10464429 doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464429] [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/10473289.2006.10464429?needAccess=true Open Access Article]</ref>. The larger tail cross section of fluorinated compared to hydrogenated amphiphiles tends to favor the formation of aggregates with lesser surface curvature, therefore rather than micelles they form bilayer membranes, vesicles, tubules and fibers<ref>Krafft, M.P., Guilieri, F., Riess, J.G., 1993. Can Single-Chain Perfluoroalkylated Amphiphiles Alone form Vesicles and Other Organized Supramolecular Systems? Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 32(5), pp. 741-743. [https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199307411 doi: 10.1002/anie.199307411]</ref><ref>Furuya, H., Moroi, Y., Kaibara, K., 1996. Solid and Solution Properties of Alkylammonium Perfluorocarboxylates. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 100(43), pp. 17249-17254. [https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9612801 doi: 10.1021/jp9612801]</ref><ref>Giulieri, F., Krafft, M.P., 1996. Self-organization of single-chain fluorinated amphiphiles with fluorinated alcohols. Thin Solid Films, 284-285, pp. 195-199. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6090(95)08304-9 doi: 10.1016/S0040-6090(95)08304-9]</ref><ref>Gladysz, J.A., Curran, D.P., Horvath, I.T., 2004. Handbook of Fluorous Chemistry. WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA,, Weinheim, Germany. ISBN: 3-527-30617-X</ref>. Rojas ''et al.'' (2002) demonstrated that perfluorooctyl sulphonamide formed a contiguous bilayer at 50 mg/L with self-assembled aggregates present at concentrations as low as 10 mg/L<ref name="RojasEtAl2002">Rojas, O.J., Macakova, L., Blomberg, E., Emmer, A., and Claesson, P.M., 2002. Fluorosurfactant Self-Assembly at Solid/Liquid Interfaces. Langmuir, 18(21), pp. 8085-8095. [https://doi.org/10.1021/la025989c doi: 10.1021/la025989c]</ref>. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | == | + | ==Thermodynamics of PFAS Accumulations on Solid Surfaces== |

| − | + | The thermodynamics of formation of amphiphiles into supramolecular species requires consideration of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions resulting from the amphoteric nature of the molecule. The hydrophilic portions of the molecule are driven to maximize their solvation interaction with as many water molecules as possible, whereas the hydrophobic portions of the molecule are driven to aggregate together thus minimizing interaction with the bulk water. Both of these processes change the [[wikipedia:Enthalpy|enthalpy]] and [[wikipedia: Entropy|entropy]] of the system. | |

| − | + | In aqueous solution, the hydrophilic portions of an amphiphile form hydrogen bonds (4 - 120 kJ/mol) and van der Waals interactions (<5 kJ/mol) with water molecules and surfaces, and electrostatic interactions (5 – 300 kJ/mol) can also occur where the amphiphile is ionic<ref name="LombardoEtAl2015">Lombardo, D., Kiselev, M.A., Magazù, S., Calandra, P., 2015. Amphiphiles Self-Assembly: Basic Concepts and Future Perspectives of Supramolecular Approaches. Advances in Condensed Matter Physics, vol. 2015, article ID 151683, 22 pages. [https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/151683 doi: 10.1155/2015/151683] [[Media: LombardoEtAl2015.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. These interactions, although weak compared to intramolecular covalent bonds within a molecule are energetically favorable and increase the enthalpy of the combined solute-solvent system. Thus, the hydrophilic portion of an amphiphile will look to maximize enthalpic gain through hydrogen bond interactions with the bulk water. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | These | + | The hydrophobic portion of an amphiphile cannot form hydrogen bonds with the bulk solution, and its presence disrupts the hydrogen bond interactions between individual water molecules within the bulk water matrix. This disruption lowers the entropy of the system by reducing the degrees of translational rotational freedom available to the bulk water. The [[wikipedia:Second law of thermodynamics|second law of thermodynamics]] dictates that a system will arrange itself to maximize its entropy. With hydrophobic species this can be achieved by their spontaneous aggregation, as the reduction in solution entropy of the aggregated system is less than that which would occur if the component parts were solvated individually. These hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions are weak, and the individual entropy gain per amphiphile upon aggregation is very small. However, taken together the overall effect on the entropy of the aggregate is sufficient to maintain it in solution, and moreover these interactions make the aggregates resistant to minor perturbations while retaining the reversibility of the self-assembled structure<ref name="LombardoEtAl2015"/>. |

| − | == | + | ==Regulatory Drivers for Transition to PFAS-Free Firefighting Formulations== |

| − | + | Regulations restricting the use and release of PFAS are being proposed and promulgated worldwide, with several enacted regulations addressing the use of aqueous film forming foams (AFFF) containing PFAS<ref name="Queensland2016">Queensland (Australia) Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, 2016. Operational Policy - Environmental Management of Firefighting Foam. 16 pages. [https://environment.des.qld.gov.au/assets/documents/regulation/firefighting-foam-policy.pdf Free Download]</ref><ref>U.S. Congress, 2019. S.1790 - National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. United States Library of Congress. [https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1790 Text and History of Law].</ref><ref>Arizona State Legislature, 2019. Title 36, Section 1696. Firefighting foam; prohibited uses; exception; definitions. [https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https://www.azleg.gov/ars/36/01696.htm Text of Law]</ref><ref>California Legislature, 2020. Senate Bill No. 1044, Chapter 308, Firefighting equipment and foam: PFAS chemicals. [https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB1044 Text and History of Law]</ref><ref>Arkansas General Assembly, 2021. An Act Concerning the Use of Certain Chemicals in Firefighting Foam; and for Other Purposes. Act 315, State of Arkansas. [https://trackbill.com/bill/arkansas-house-bill-1351-concerning-the-use-of-certain-chemicals-in-firefighting-foam/2008913/ Text and History of Law].</ref><ref>Espinosa, Summers, Kelly, J., Statler, Hansen, Young, 2021. Amendment to Fire Prevention and Control Act. House Bill 2722. West Virginia Legislature. [https://trackbill.com/bill/west-virginia-house-bill-2722-prohibiting-the-use-of-class-b-fire-fighting-foam-for-testing-purposes-if-the-foam-contains-a-certain-class-of-fluorinated-organic-chemicals/2047674/ Text and History of Law]</ref><ref>Louisiana Legislature, 2021. Act No. 232. [https://trackbill.com/bill/louisiana-house-bill-389-fire-protect-fire-marshal-provides-relative-to-the-discharge-or-use-of-class-b-fire-fighting-foam-containing-fluorinated-organic-chemicals/2092535/ Text and History of Law]</ref><ref>Vermont Legislature, 2021b. Act No. 36, PFAS in Class B Firefighting Foam. [https://trackbill.com/bill/vermont-senate-bill-20-an-act-relating-to-restrictions-on-perfluoroalkyl-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-and-other-chemicals-of-concern-in-consumer-products/1978963/ History and Text of Law]</ref>. In addition to regulated usage, firefighting formulation users are transitioning to PFAS-free firefighting formulations to reduce environmental liability in the event of a release, to reduce the cost of expensive containment systems and management of generated waste streams, and to avoid reputational damage. In 2016, Queensland, Australia was one of the first governments to ban PFAS use in firefighting foam<ref name="Queensland2016"/>. The US 2020 National Defense Authorization Act specified immediate prohibition of controlled releases of AFFF containing PFAS and required the Secretary of the Navy to publish a specification for PFAS-free firefighting formulation use and ensure it is available for use by the Department of Defense (DoD) by October 1, 2023<ref>U.S. Congress, 2021. S.2792 - National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021. United States Library of Congress. [https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2792/ Text and History of Law].</ref>. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) recently removed the requirement for AFFF containing PFAS from their Standard on Aircraft Hangars and added two new chapters to allow users to determine if AFFF containing PFAS is needed at their facility<ref name="NFPA2022">National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), 2022. Codes and Standards, 409: Standard on Aircraft Hangars. [https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/4/0/9/409?l=42 NFPA Website]</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Selection of Replacement PFAS-Free Firefighting Formulations== | |

| + | Since they first entered the market in the 2000s, the operational capabilities of PFAS-free firefighting formulations have grown<ref>Allcorn, M., Bluteau, T., Corfield, J., Day, G., Cornelsen, M., Holmes, N.J.C., Klein, R.A., McDowall, J.G., Olsen, K.T., Ramsden, N., Ross, I., Schaefer, T.H., Weber, R., Whitehead, K., 2018. Fluorine-Free Firefighting Foams (3F) – Viable Alternatives to Fluorinated Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFF). White Paper prepared for the IPEN by members of the IPEN F3 Panel and associates, POPRC-14, Rome. [https://ipen.org/sites/default/files/documents/IPEN_F3_Position_Paper_POPRC-14_12September2018d.pdf Free Download].</ref> and numerous companies are now manufacturing and delivering PFAS-free firefighting formulations for fixed systems and AFFF vehicles<ref>Ansul (Company), Ansul NFF-331 3%x3% Non-Fluorinated Foam Concentrate (Commercial Product). [https://docs.johnsoncontrols.com/specialhazards/api/khub/documents/1nbeVfynU1IW~eJcCOA0Bg/content Product Data Sheet].</ref><ref>BioEx (Company), Ecopol A+ (Commercial Product). [https://www.bio-ex.com/en/our-products/product/ecopol-aplus/ Website]</ref><ref>National Foam (Company), 2020. Avio F3 Green KHC 3%, Fluorine Free Foam Concentrate (Commercial Product). [https://nationalfoam.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/NMS515-Avio-Green-KHC-3-FF.pdf Safety Data Sheet]</ref>. Key factors in the selection of a PFAS-free firefighting formulation product are compatibility of the new formulation with the existing system (as confirmed by a fire protection engineer) and environmental certifications (i.e., verifying the absence of organic fluorine or PFAS or the absence of other non-fluorine environmental contaminants). | ||

| − | + | In January 2023, the US Department of Defense (DoD) published the [https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jan/12/2003144157/-1/-1/1/MILITARY-SPECIFICATION-FOR-FIRE-EXTINGUISHING-AGENT-FLUORINE-FREE-FOAM-F3-LIQUID-CONCENTRATE-FOR-LAND-BASED-FRESH-WATER-APPLICATIONS.PDF Performance Specification for Fire Extinguishing Agent, Fluorine-Free Foam (F3) Liquid Concentrate for Land-Based, Fresh Water Applications]<ref name="DoD2023"/>. This Military Performance Specification (Mil-Spec) allows PFAS-free firefighting formulations to be certified as meeting certain standardized operational goals for use in military settings. In addition to Mil-Spec requirements, PFAS-free firefighting formulations can also be certified through Underwriters Laboratories Standard for Safety, Foam Equipment and Liquid Concentrates, UL 162, which requires the new firefighting formulations be investigated for suitability and compatibility with the specific equipment with which they are intended to be used<ref>Underwriters Laboratories Inc., 2018. UL162, UL Standard for Safety, Foam Equipment and Liquid Concentrates, 8th Edition, Revised 2022. 40 pages. [https://global.ihs.com/doc_detail.cfm?document_name=UL%20162&item_s_key=00096960 Website]</ref>. Several PFAS-free foams have been certified under various parts of EN1568, the European Standard which specifies the necessary foam properties and performance requirements<ref>CSN EN 1568-1 ed. 2, 2018. Fire extinguishing media - Foam concentrates - Part 1: Specification for medium expansion foam concentrates for surface application to water-immiscible liquids. 48 pages. [https://www.en-standard.eu/csn-en-1568-1-ed-2-fire-extinguishing-media-foam-concentrates-part-1-specification-for-medium-expansion-foam-concentrates-for-surface-application-to-water-immiscible-liquids/ European Standards Website.]</ref>. Both [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ ESTCP and SERDP] have supported (and continue to support) the development and field validation of PFAS-free firefighting formulations (e.g. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/baa72637-e3c8-40ee-a007-f295311c72ad WP22-7456], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/1bed98f7-dbe6-4bdd-98d2-1f9cfeb5f3d9/wp21-3465-project-overview WP21-3465], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/bc932800-cfc8-4e86-a212-5f8c9d27f17c WP20-1535]). Both the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) have performed a variety of foam certification tests on numerous PFAS-free firefighting formulations<ref>Back, G.G., Farley, J.P., 2020. Evaluation of the Fire Protection Effectiveness of Fluorine Free Firefighting Foams. National Fire Protection Association, Fire Protection Research Foundation. [https://www.iafc.org/docs/default-source/1safehealthshs/effectivenessofflourinefreefoam.pdf Free Download].</ref><ref>Casey, J., Trazzi, D., 2022. Fluorine-Free Foam Testing. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Final Report. [https://www.airporttech.tc.faa.gov/DesktopModules/EasyDNNNews/DocumentDownload.ashx?portalid=0&moduleid=3682&articleid=2882&documentid=3054 Open Access Article]</ref>. | |

| − | + | ==Selection of Flushing Agent== | |

| + | General industry guidance has typically recommended several rinses with water to remove PFAS from impacted equipment. Owing to the unique physical and chemical properties of PFAS, the use of room temperature water to remove PFAS from impacted equipment has not been very effective. To address these recalcitrant accumulations, companies are developing new methods to remove self-assembled PFAS bilayers from existing fire-fighting infrastructure so that it can be successfully transitioned to PFAS-free formulations. Arcadis developed a non-toxic cleaning agent, Fluoro Fighter<sup>TM</sup>, which has been demonstrated to be effective for removal of PFAS from equipment by disrupting the accumulated layers of PFAS coating the AFFF-wetted surfaces. | ||

| − | = | + | Laboratory studies have supported the optimization of this PFAS removal method in fire suppression system piping obtained from a commercial airport hangar in Sydney, Australia<ref name="LangEtAl2022"/>. Prior to removal from the hangar, the stainless-steel pipe held PFAS-containing AFFF for more than three decades. Results indicated that Fluoro Fighter<sup>TM</sup>, as well as flushing at elevated temperatures, removed more surface associated PFAS in comparison to equivalent extractions using methanol or water at room temperature. ESTCP has supported (and continues to support) the development and field validation of best practices for methodologies to clean foam delivery systems (e.g. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/1521652f-a8b2-4c52-9232-c1018989a6b1 ER20-5364], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/6d0750be-f20b-4765-bdfa-872adccaf37a ER20-5361], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/0aa2fb20-b851-4b5b-ac64-e72795986b8a ER20-5369], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/4fd2e4ab-ddb7-40f8-835e-e1d637c0d650 ER21-7229]). |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==PFAS Verification Testing== | |

| + | In general, PFAS sampling techniques used to support firefighting formulation transition activities are consistent with conventional sampling techniques used in the environmental industry, but special consideration is made regarding high concentration PFAS materials, elevated detection levels, cross-contamination potential, precursor content, and matrix interferences. The analytical method selected should be appropriate for the regulatory requirements in the site area. | ||

| − | + | ==Rinsate Treatment== | |

| + | Numerous technologies for treatment of PFAS-impacted water sources, including rinsates, have been and are currently being developed. These include separation technologies such as [[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment|foam fractionation, nanofiltration, sorbents/flocculants, ion exchange resins, reverse osmosis, and destructive technologies such as sonolysis, electrochemical oxidation, hydrothermal alkaline treatment]], [[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma |enhanced contact plasma]], and [[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO) |supercritical water oxidation (SCWO)]]. Many of these technologies have rapidly developed from bench-scale (e.g., microcosms, columns, single reactors) to commercially available field-scale units capable of managing PFAS-impacted waters of varying waste volumes and PFAS compositions and concentrations. Ongoing field research continues to improve the treatment efficiency, reliability, and versatility of these technologies, both individually and as coupled treatment solutions (e.g., treatment train). ESTCP has supported (and continues to support) the development and field validation of separation and destructive technologies for treatment of PFAS-impacted water sources, including rinsates (e.g. ER20-5370, ER20-5369, ER20-5350, ER20-5355). | ||

| − | + | Remedy selection for treatment of rinsates involves several key factors. It is critical that environmental practitioners have up-to-date technical and practical knowledge on the suitability of these remedial options for different site conditions, treatment volumes, PFAS composition (e.g., presence of precursors, co-contaminants), PFAS concentrations, safety considerations, potential for undesired byproducts (e.g., perchlorate, disinfection byproducts), and treatment costs (e.g., energy demand, capital costs, operational labor). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | <references/> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 21:39, 28 March 2024

Transition of Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) Fire Suppression Infrastructure Impacted by Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contained in Class B aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) are known to accumulate on wetted surfaces of many fire suppression systems after decades of exposure[1]. When replacement PFAS-free firefighting formulations are added to existing infrastructure, PFAS can rebound from the wetted surfaces into the new formulations at high concentrations[2][3]. Effective methods are needed to properly transition to PFAS-free firefighting formulations in existing fire suppression infrastructure. Considerations in the transition process may include but are not limited to locating, identifying, and evaluating existing systems and AFFF, fire engineering evaluations, system prioritization, cost/downtime analyses, sampling and analysis, evaluation of risks and hazards to human health and the environment, transportation, and disposal.

Contents

- 1 Transition of Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) Fire Suppression Infrastructure Impacted by Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- 2 Introduction

- 3 PFAS Assembly on Solid Surfaces

- 4 Thermodynamics of PFAS Accumulations on Solid Surfaces

- 5 Regulatory Drivers for Transition to PFAS-Free Firefighting Formulations

- 6 Selection of Replacement PFAS-Free Firefighting Formulations

- 7 Selection of Flushing Agent

- 8 PFAS Verification Testing

- 9 Rinsate Treatment

- 10 References

- 11 See Also

Related Article(s):

- Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

Contributor(s):

- Dr. Johnsie Ray Lang

- Dr. Jonathan Miles

- John Anderson

- Dr. Theresa Guillette

- Dr. Craig Divine

- Dr. Stephen Richardson

Key Resource(s):

- Department of Defense (DoD) performance standard for PFAS-free firefighting formulation: Military Specification MIL-PRF-32725[4]

- Characterization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on fire suppression system piping and optimization of removal methods[1]

Introduction

PFAS are a class of synthetic fluorinated compounds which are highly mobile and persistent within the environment[5]. Due to the surfactant properties of PFAS, these compounds self-assemble at any solid-liquid interface forming resilient bilayers during prolonged exposure[6]. Solid phase accumulation of PFAS has been proposed to be influenced by both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions with fluorinated carbon chain length as the dominant feature influencing sorption[7]. While the majority of previous research into solid phase sorption typically focused on water treatment applications or subsurface porous media[8], recently PFAS accumulations have been identified on the wetted surfaces of fire suppression infrastructure exposed to aqueous film forming foam (AFFF)[1] (see Figure 1).

Fire suppression systems with potential PFAS impacts include fire fighting vehicles that carried AFFF and fixed suppression systems in buildings containing large amounts of flammable materials such as aircraft hangars (Figure 2). PFAS residue on the wetted surfaces of existing infrastructure can rebound into replacement PFAS-free firefighting formulations if not removed during the transition process[2]. Simple surface rinsing with water and low-pressure washing has been proven to be inefficient for removal of surface bound PFAS from piping and tanks that contained fluorinated AFFF[2]

In addition to proper methods for system cleaning to remove residual PFAS, transition to PFAS-free foam may also include consideration of compliance with state and federal regulations, selection of the replacement PFAS-free firefighting formulation, a cost benefit analysis for replacement of the system components versus cleaning, and PFAS verification testing. Foam transition should be completed in a manner which minimizes the volume of waste generated as well as preventing any PFAS release into the environment.

PFAS Assembly on Solid Surfaces

The self-assembly of amphiphilic molecules into supramolecular bilayers is a result of their structure and how it interacts with the bulk water of a solution. Single chain hydrocarbon based amphiphiles can form micelles under relatively dilute aqueous concentrations, however for hydrocarbon based surfactants the formation of more complex organized system such as vesicles is rarely seen, requiring double chain amphiphiles such as phospholipids. Associations of single chain cationic and anionic hydrocarbon based amphiphiles into stable supramolecular structures such as vesicles has however been demonstrated[9], with the ion pairing of the polar head groups mimicking the a double tail situation. The behavior of single chain fluorosurfactant amphiphiles has been demonstrated to be significantly different from similar hydrocarbon based analogues. Not only are critical micelle concentrations (CMC) of fluorosurfactants typically two orders of magnitude lower than corresponding hydrocarbon surfactants but self-assembly can occur even when fluorosurfactants are dispersed at low concentrations significantly below the CMC in water and other solvents[10]. The assembly of fluorinated amphiphiles structurally similar to those found in AFFF have been shown to readily form stable, complex structures including vesicles, fibers, and globules at concentrations as low as 0.5% w/v in contrast to their hydrocarbon analogues which remained fluid at 30% w/v[11][12].

Krafft found that fluorinated amphiphiles formed bilayer membranes with phospholipids, and that the resulting vesicles were more stable than those made of phospholipids alone[13]. The similarities in amphiphilic properties between phospholipids and the hydrocarbon-based surfactants in AFFF suggests that bilayer vesicles may form between these and the fluorosurfactants also present in the concentrate. Krafft demonstrated that both the permeability of resulting mixed vesicles and their propensity to fuse with each other at increasing ionic strength was reduced as a result of the creation of an inert hydrophobic and lipophobic film within the membrane, and also suggested that the fluorinated amphiphiles increased van der Waals interactions in the hydrocarbon region[13]. Thus this low permeability may allow vesicles formed by the surfactants present in AFFF to act as long term repositories of PFAS not only as part of the bilayer itself but also solvated within the vesicle. This prediction is supported by the observation that supramolecular structures formed from single chain fluorinated amphiphiles have been demonstrated to be stable at elevated temperature (15 min at 121°C) and have been shown to be stable over periods of months, even increasing in size over time when stored at environmentally relevant temperatures[12].

Formation of complex structures at relatively low solute concentrations requires the monomer molecules to be well ordered to maintain tight packing in the supramolecular structure[14]. This order results from electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding, and in the case of fluorinated amphiphiles, hydrophobic interactions. The geometry of the amphiphile also potentially contributes to the type of supramolecular aggregation[15]. Surfactants which adopt a conical shape (such as a typical hydrocarbon based surfactant with a large polar head group and a single alkyl chain as a tail) tend to form micelles more easily. Increasing the bulk of the tail makes the surfactant more cylindrically shaped which makes assembly into bilayers more likely.

Perfluoroalkyl chains are significantly more bulky than their hydrocarbon based analogues both in cross sectional area (28-30 Å2 versus 20 Å2, respectively) and mean volume (CF2 and CF3 estimated as 38 Å3 and 92 Å3 compared to 27 Å3 and 54 Å3 for CH2 and CH3)[13][10]. Structural studies on linear PFOS have shown that the molecule adopts an unusual helical structure[16][17] in aqueous and solvent phases to alleviate steric hindrance. This arrangement results from the carbon chain starting in the planar all anti conformation and then successively twisting all the CC-CC dihedrals by 15°-20° in the same direction[18]. The conformation also minimizes the electrostatic repulsion between fluorine atoms bonded to the same side of the carbon backbone by maximizing the interatomic distances between them[17].

A consequence of the helical structure is that there is limited carbon-carbon bond rotation within the perfluoroalkyl chain giving them increased rigidity compared to alkyl chains[19]. The bulkiness of the perfluoroalkyl chain confers a cylindrical shape on the fluorosurfactant amphiphile and therefore favors the formation of bilayers and vesicles the aggregation of which is further assisted by the rigidity of the molecules which allow close packing in the supramolecular structure. Fluorosurfactants therefore cannot be regarded as more hydrophobic analogues of hydrogenated surfactants. Their self-assembly behavior is characterized by a strong tendency to form vesicles and lamellar phases rather than micelles, due to the bulkiness and rigidity of the perfluoroalkyl chain that tends to decrease the curvature of the aggregates they form in solution[20]. The larger tail cross section of fluorinated compared to hydrogenated amphiphiles tends to favor the formation of aggregates with lesser surface curvature, therefore rather than micelles they form bilayer membranes, vesicles, tubules and fibers[21][22][23][24]. Rojas et al. (2002) demonstrated that perfluorooctyl sulphonamide formed a contiguous bilayer at 50 mg/L with self-assembled aggregates present at concentrations as low as 10 mg/L[25].

Thermodynamics of PFAS Accumulations on Solid Surfaces

The thermodynamics of formation of amphiphiles into supramolecular species requires consideration of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions resulting from the amphoteric nature of the molecule. The hydrophilic portions of the molecule are driven to maximize their solvation interaction with as many water molecules as possible, whereas the hydrophobic portions of the molecule are driven to aggregate together thus minimizing interaction with the bulk water. Both of these processes change the enthalpy and entropy of the system.

In aqueous solution, the hydrophilic portions of an amphiphile form hydrogen bonds (4 - 120 kJ/mol) and van der Waals interactions (<5 kJ/mol) with water molecules and surfaces, and electrostatic interactions (5 – 300 kJ/mol) can also occur where the amphiphile is ionic[26]. These interactions, although weak compared to intramolecular covalent bonds within a molecule are energetically favorable and increase the enthalpy of the combined solute-solvent system. Thus, the hydrophilic portion of an amphiphile will look to maximize enthalpic gain through hydrogen bond interactions with the bulk water.

The hydrophobic portion of an amphiphile cannot form hydrogen bonds with the bulk solution, and its presence disrupts the hydrogen bond interactions between individual water molecules within the bulk water matrix. This disruption lowers the entropy of the system by reducing the degrees of translational rotational freedom available to the bulk water. The second law of thermodynamics dictates that a system will arrange itself to maximize its entropy. With hydrophobic species this can be achieved by their spontaneous aggregation, as the reduction in solution entropy of the aggregated system is less than that which would occur if the component parts were solvated individually. These hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions are weak, and the individual entropy gain per amphiphile upon aggregation is very small. However, taken together the overall effect on the entropy of the aggregate is sufficient to maintain it in solution, and moreover these interactions make the aggregates resistant to minor perturbations while retaining the reversibility of the self-assembled structure[26].

Regulatory Drivers for Transition to PFAS-Free Firefighting Formulations

Regulations restricting the use and release of PFAS are being proposed and promulgated worldwide, with several enacted regulations addressing the use of aqueous film forming foams (AFFF) containing PFAS[27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34]. In addition to regulated usage, firefighting formulation users are transitioning to PFAS-free firefighting formulations to reduce environmental liability in the event of a release, to reduce the cost of expensive containment systems and management of generated waste streams, and to avoid reputational damage. In 2016, Queensland, Australia was one of the first governments to ban PFAS use in firefighting foam[27]. The US 2020 National Defense Authorization Act specified immediate prohibition of controlled releases of AFFF containing PFAS and required the Secretary of the Navy to publish a specification for PFAS-free firefighting formulation use and ensure it is available for use by the Department of Defense (DoD) by October 1, 2023[35]. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) recently removed the requirement for AFFF containing PFAS from their Standard on Aircraft Hangars and added two new chapters to allow users to determine if AFFF containing PFAS is needed at their facility[36].

Selection of Replacement PFAS-Free Firefighting Formulations

Since they first entered the market in the 2000s, the operational capabilities of PFAS-free firefighting formulations have grown[37] and numerous companies are now manufacturing and delivering PFAS-free firefighting formulations for fixed systems and AFFF vehicles[38][39][40]. Key factors in the selection of a PFAS-free firefighting formulation product are compatibility of the new formulation with the existing system (as confirmed by a fire protection engineer) and environmental certifications (i.e., verifying the absence of organic fluorine or PFAS or the absence of other non-fluorine environmental contaminants).

In January 2023, the US Department of Defense (DoD) published the Performance Specification for Fire Extinguishing Agent, Fluorine-Free Foam (F3) Liquid Concentrate for Land-Based, Fresh Water Applications[4]. This Military Performance Specification (Mil-Spec) allows PFAS-free firefighting formulations to be certified as meeting certain standardized operational goals for use in military settings. In addition to Mil-Spec requirements, PFAS-free firefighting formulations can also be certified through Underwriters Laboratories Standard for Safety, Foam Equipment and Liquid Concentrates, UL 162, which requires the new firefighting formulations be investigated for suitability and compatibility with the specific equipment with which they are intended to be used[41]. Several PFAS-free foams have been certified under various parts of EN1568, the European Standard which specifies the necessary foam properties and performance requirements[42]. Both ESTCP and SERDP have supported (and continue to support) the development and field validation of PFAS-free firefighting formulations (e.g. WP22-7456, WP21-3465, WP20-1535). Both the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) have performed a variety of foam certification tests on numerous PFAS-free firefighting formulations[43][44].

Selection of Flushing Agent

General industry guidance has typically recommended several rinses with water to remove PFAS from impacted equipment. Owing to the unique physical and chemical properties of PFAS, the use of room temperature water to remove PFAS from impacted equipment has not been very effective. To address these recalcitrant accumulations, companies are developing new methods to remove self-assembled PFAS bilayers from existing fire-fighting infrastructure so that it can be successfully transitioned to PFAS-free formulations. Arcadis developed a non-toxic cleaning agent, Fluoro FighterTM, which has been demonstrated to be effective for removal of PFAS from equipment by disrupting the accumulated layers of PFAS coating the AFFF-wetted surfaces.

Laboratory studies have supported the optimization of this PFAS removal method in fire suppression system piping obtained from a commercial airport hangar in Sydney, Australia[1]. Prior to removal from the hangar, the stainless-steel pipe held PFAS-containing AFFF for more than three decades. Results indicated that Fluoro FighterTM, as well as flushing at elevated temperatures, removed more surface associated PFAS in comparison to equivalent extractions using methanol or water at room temperature. ESTCP has supported (and continues to support) the development and field validation of best practices for methodologies to clean foam delivery systems (e.g. ER20-5364, ER20-5361, ER20-5369, ER21-7229).

PFAS Verification Testing

In general, PFAS sampling techniques used to support firefighting formulation transition activities are consistent with conventional sampling techniques used in the environmental industry, but special consideration is made regarding high concentration PFAS materials, elevated detection levels, cross-contamination potential, precursor content, and matrix interferences. The analytical method selected should be appropriate for the regulatory requirements in the site area.

Rinsate Treatment

Numerous technologies for treatment of PFAS-impacted water sources, including rinsates, have been and are currently being developed. These include separation technologies such as foam fractionation, nanofiltration, sorbents/flocculants, ion exchange resins, reverse osmosis, and destructive technologies such as sonolysis, electrochemical oxidation, hydrothermal alkaline treatment, enhanced contact plasma, and supercritical water oxidation (SCWO). Many of these technologies have rapidly developed from bench-scale (e.g., microcosms, columns, single reactors) to commercially available field-scale units capable of managing PFAS-impacted waters of varying waste volumes and PFAS compositions and concentrations. Ongoing field research continues to improve the treatment efficiency, reliability, and versatility of these technologies, both individually and as coupled treatment solutions (e.g., treatment train). ESTCP has supported (and continues to support) the development and field validation of separation and destructive technologies for treatment of PFAS-impacted water sources, including rinsates (e.g. ER20-5370, ER20-5369, ER20-5350, ER20-5355).

Remedy selection for treatment of rinsates involves several key factors. It is critical that environmental practitioners have up-to-date technical and practical knowledge on the suitability of these remedial options for different site conditions, treatment volumes, PFAS composition (e.g., presence of precursors, co-contaminants), PFAS concentrations, safety considerations, potential for undesired byproducts (e.g., perchlorate, disinfection byproducts), and treatment costs (e.g., energy demand, capital costs, operational labor).

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lang, J.R., McDonough, J., Guillette, T.C., Storch, P., Anderson, J., Liles, D., Prigge, R., Miles, J.A.L., Divine, C., 2022. Characterization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on fire suppression system piping and optimization of removal methods. Chemosphere, 308(Part 2), 136254. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136254 Open Access Article

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ross, I., and Storch, P., 2020. Foam Transition: Is It as Simple as "Foam Out / Foam In?". The Catalyst (Journal of JOIFF, The International Organization for Industrial Emergency Services Management), Q2 Supplement, 20 pages. Industry Newsletter

- ^ Kappetijn, K., 2023. Replacement of fluorinated extinguishing foam: When is clean clean enough? The Catalyst (Journal of JOIFF, The International Organization for Industrial Emergency Services Management), Q1 2023, pp. 31-33. Industry Newsletter

- ^ 4.0 4.1 US Department of Defense, 2023. Performance Specification for Fire Extinguishing Agent, Fluorine-Free Foam (F3) Liquid Concentrate for Land-Based, Fresh Water Applications. Mil-Spec MIL-PRF-32725, 18 pages. Military Specification Document

- ^ Giesy, J.P., Kannan, K., 2001. Global Distribution of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Wildlife. Environmental Science and Technology 35(7), pp. 1339-1342. doi: 10.1021/es001834k

- ^ Krafft, M.P., Riess, J.G., 2015. Selected physicochemical aspects of poly- and perfluoroalkylated substances relevant to performance, environment and sustainability-Part one. Chemosphere, 129, pp. 4-19. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.039

- ^ Higgins, C.P., Luthy, R.G., 2006. Sorption of Perfluorinated Surfactants on Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(23), pp. 7251-7256. doi: 10.1021/es061000n

- ^ Brusseau, M.L., 2018. Assessing the Potential Contributions of Additional Retention Processes to PFAS Retardation in the Subsurface. Science of the Total Environment, 613-614, pp. 176-185. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.065 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ Fukuda, H., Kawata, K., Okuda, H., 1990. Bilayer-Forming Ion-Pair Amphiphiles from Single-Chain Surfactants. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 112(4), pp. 1635-1637. doi: 10.1021/ja00160a057

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Krafft, M.P., 2006. Highly fluorinated compounds induce phase separation in, and nanostructuration of liquid media. Possible impact on, and use in chemical reactivity control. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 44(14), pp. 4251-4258. doi: 10.1002/pola.21508 Open Access Article

- ^ Krafft, M.P., Guilieri, F., Riess, J.G., 1993. Can Single-Chain Perfluoroalkylated Amphiphiles Alone form Vesicles and Other Organized Supramolecular Systems? Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 32(5), pp. 741-743. doi: 10.1002/anie.199307411

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Krafft, M.P., Guilieri, F., Riess, J.G., 1994. Supramolecular assemblies from single chain perfluoroalkylated phosphorylated amphiphiles. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 84(1), pp. 113-119. doi: 10.1016/0927-7757(93)02681-4

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Krafft, M.P., Riess, J.G., 1998. Highly Fluorinated Amphiphiles and Collodial Systems, and their Applications in the Biomedical Field. A Contribution. Biochimie, 80(5-6), pp. 489-514. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(00)80016-4

- ^ Ringsdorf, H., Schlarb, B., Venzmer, J., 1988. Molecular Architecture and Function of Polymeric Oriented Systems: Models for the Study of Organization, Surface Recognition, and Dynamics of Biomembranes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 27(1), pp. 113-158. doi: 10.1002/anie.198801131

- ^ Israelachvili, J.N., Mitchell, D.J., Ninham, B.W., 1976. Theory of Self-Assembly of Hydrocarbon Amphiphiles into Micelles and Bilayers. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 2: Molecular and Chemical Physics, 72, pp. 1525-1568. doi: 10.1039/F29767201525

- ^ Erkoç, Ş., Erkoç, F., 2001. Structural and electronic properties of PFOS and LiPFOS. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM, 549(3), pp. 289-293. doi:10.1016/S0166-1280(01)00553-X

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Torres, F.J., Ochoa-Herrera, V., Blowers, P., Sierra-Alvarez, R., 2009. Ab initio study of the structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and its branched isomers. Chemosphere 76(8), pp. 1143-1149. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.04.009

- ^ Abbandonato, G., Catalano, D., Marini, A., 2010. Aggregation of Perfluoroctanoate Salts Studied by 19F NMR and DFT Calculations: Counterion Complexation, Poly(ethylene glycol) Addition, and Conformational Effects. Langmuir 26(22), pp. 16762-16770. doi: 10.1021/la102578k.

- ^ Barton, S.W., Goudot, A., Bouloussa, O., Rondelez, F., Lin, B., Novak, F., Acero, A., Rice, S., 1992. Structural transitions in a monolayer of fluorinated amphiphile molecules. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 96(2), pp. 1343-1351. doi: 10.1063/1.462170

- ^ Barton, C.A., Butler, L.E., Zarzecki, C.J., Flaherty, J., Kaiser, M., 2006. Characterizing Perfluorooctanoate in Ambient Air near the Fence Line of a Manufacturing Facility: Comparing Modeled and Monitored Values. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, 56, pp. 48-55. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464429 Open Access Article

- ^ Krafft, M.P., Guilieri, F., Riess, J.G., 1993. Can Single-Chain Perfluoroalkylated Amphiphiles Alone form Vesicles and Other Organized Supramolecular Systems? Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 32(5), pp. 741-743. doi: 10.1002/anie.199307411

- ^ Furuya, H., Moroi, Y., Kaibara, K., 1996. Solid and Solution Properties of Alkylammonium Perfluorocarboxylates. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 100(43), pp. 17249-17254. doi: 10.1021/jp9612801

- ^ Giulieri, F., Krafft, M.P., 1996. Self-organization of single-chain fluorinated amphiphiles with fluorinated alcohols. Thin Solid Films, 284-285, pp. 195-199. doi: 10.1016/S0040-6090(95)08304-9

- ^ Gladysz, J.A., Curran, D.P., Horvath, I.T., 2004. Handbook of Fluorous Chemistry. WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA,, Weinheim, Germany. ISBN: 3-527-30617-X

- ^ Rojas, O.J., Macakova, L., Blomberg, E., Emmer, A., and Claesson, P.M., 2002. Fluorosurfactant Self-Assembly at Solid/Liquid Interfaces. Langmuir, 18(21), pp. 8085-8095. doi: 10.1021/la025989c

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Lombardo, D., Kiselev, M.A., Magazù, S., Calandra, P., 2015. Amphiphiles Self-Assembly: Basic Concepts and Future Perspectives of Supramolecular Approaches. Advances in Condensed Matter Physics, vol. 2015, article ID 151683, 22 pages. doi: 10.1155/2015/151683 Open Access Article

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Queensland (Australia) Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, 2016. Operational Policy - Environmental Management of Firefighting Foam. 16 pages. Free Download

- ^ U.S. Congress, 2019. S.1790 - National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. United States Library of Congress. Text and History of Law.

- ^ Arizona State Legislature, 2019. Title 36, Section 1696. Firefighting foam; prohibited uses; exception; definitions. Text of Law

- ^ California Legislature, 2020. Senate Bill No. 1044, Chapter 308, Firefighting equipment and foam: PFAS chemicals. Text and History of Law

- ^ Arkansas General Assembly, 2021. An Act Concerning the Use of Certain Chemicals in Firefighting Foam; and for Other Purposes. Act 315, State of Arkansas. Text and History of Law.

- ^ Espinosa, Summers, Kelly, J., Statler, Hansen, Young, 2021. Amendment to Fire Prevention and Control Act. House Bill 2722. West Virginia Legislature. Text and History of Law

- ^ Louisiana Legislature, 2021. Act No. 232. Text and History of Law

- ^ Vermont Legislature, 2021b. Act No. 36, PFAS in Class B Firefighting Foam. History and Text of Law

- ^ U.S. Congress, 2021. S.2792 - National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021. United States Library of Congress. Text and History of Law.

- ^ National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), 2022. Codes and Standards, 409: Standard on Aircraft Hangars. NFPA Website

- ^ Allcorn, M., Bluteau, T., Corfield, J., Day, G., Cornelsen, M., Holmes, N.J.C., Klein, R.A., McDowall, J.G., Olsen, K.T., Ramsden, N., Ross, I., Schaefer, T.H., Weber, R., Whitehead, K., 2018. Fluorine-Free Firefighting Foams (3F) – Viable Alternatives to Fluorinated Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFF). White Paper prepared for the IPEN by members of the IPEN F3 Panel and associates, POPRC-14, Rome. Free Download.

- ^ Ansul (Company), Ansul NFF-331 3%x3% Non-Fluorinated Foam Concentrate (Commercial Product). Product Data Sheet.

- ^ BioEx (Company), Ecopol A+ (Commercial Product). Website

- ^ National Foam (Company), 2020. Avio F3 Green KHC 3%, Fluorine Free Foam Concentrate (Commercial Product). Safety Data Sheet

- ^ Underwriters Laboratories Inc., 2018. UL162, UL Standard for Safety, Foam Equipment and Liquid Concentrates, 8th Edition, Revised 2022. 40 pages. Website

- ^ CSN EN 1568-1 ed. 2, 2018. Fire extinguishing media - Foam concentrates - Part 1: Specification for medium expansion foam concentrates for surface application to water-immiscible liquids. 48 pages. European Standards Website.

- ^ Back, G.G., Farley, J.P., 2020. Evaluation of the Fire Protection Effectiveness of Fluorine Free Firefighting Foams. National Fire Protection Association, Fire Protection Research Foundation. Free Download.

- ^ Casey, J., Trazzi, D., 2022. Fluorine-Free Foam Testing. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Final Report. Open Access Article