Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Remediation Technologies) |

(→Technical Performance) |

||

| (547 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination PFAS Destruction== |

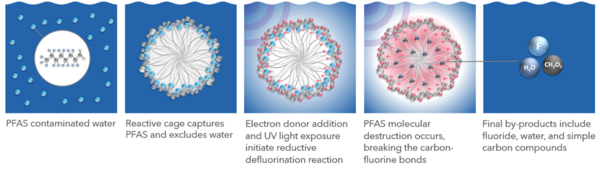

| − | + | Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination (PRD) is a [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] destruction technology predicated on [[Wikipedia: Ultraviolet | ultraviolet (UV)]] light-activated photochemical reactions. The destruction efficiency of this process is enhanced by the use of a [[Wikipedia: Surfactant | surfactant]] to confine PFAS molecules in self-assembled [[Wikipedia: Micelle | micelles]]. The photochemical reaction produces [[Wikipedia: Solvated electron | hydrated electrons]] from an electron donor that associates with the micelle. The hydrated electrons have sufficient energy to rapidly cleave fluorine-carbon and other molecular bonds of PFAS molecules due to the association of the electron donor with the micelle. Micelle-accelerated PRD is a highly efficient method to destroy PFAS in a wide variety of water matrices. | |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[PFAS Sources]] |

| + | *[[PFAS Transport and Fate]] | ||

| + | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] | ||

| + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] | ||

| + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] | ||

| − | '''Contributor(s):''' | + | '''Contributor(s):''' |

| + | *Dr. Suzanne Witt | ||

| + | *Dr. Meng Wang | ||

| + | *Dr. Denise Kay | ||

'''Key Resource(s):''' | '''Key Resource(s):''' | ||

| − | * | + | *Efficient Reductive Destruction of Perfluoroalkyl Substances under Self-Assembled Micelle Confinement<ref name="ChenEtAl2020">Chen, Z., Li, C., Gao, J., Dong, H., Chen, Y., Wu, B., Gu, C., 2020. Efficient Reductive Destruction of Perfluoroalkyl Substances under Self-Assembled Micelle Confinement. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(8), pp. 5178–5185. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b06599 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b06599]</ref> |

| − | + | *Complete Defluorination of Perfluorinated Compounds by Hydrated Electrons Generated from 3-Indole-Acetic-Acid in Organomodified Montmorillonite<ref name="TianEtAl2016">Tian, H., Gao, J., Li, H., Boyd, S.A., Gu, C., 2016. Complete Defluorination of Perfluorinated Compounds by Hydrated Electrons Generated from 3-Indole-Acetic-Acid in Organomodified Montmorillonite. Scientific Reports, 6(1), Article 32949. [https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32949 doi: 10.1038/srep32949] [[Media: TianEtAl2016.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> | |

| − | * | + | *Application of Surfactant Modified Montmorillonite with Different Conformation for Photo-Treatment of Perfluorooctanoic Acid by Hydrated Electrons<ref name="ChenEtAl2019">Chen, Z., Tian, H., Li, H., Li, J. S., Hong, R., Sheng, F., Wang, C., Gu, C., 2019. Application of Surfactant Modified Montmorillonite with Different Conformation for Photo-Treatment of Perfluorooctanoic Acid by Hydrated Electrons. Chemosphere, 235, pp. 1180–1188. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.032 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.032]</ref> |

| − | + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/c4e21fa2-c7e2-4699-83a9-3427dd484a1a ER21-7569: Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination PFAS Destruction]<ref name="WittEtAl2023">Kay, D., Witt, S., Wang, M., 2023. Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination PFAS Destruction: Final Report. ESTCP Project ER21-7569. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/c4e21fa2-c7e2-4699-83a9-3427dd484a1a Project Website] [[Media: ER21-7569_Final_Report.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref> | |

| − | |||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:WittFig1.png | thumb |600px|Figure 1. Schematic of PRD mechanism<ref name="WittEtAl2023"/>]] |

| + | The Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination (PRD) process is based on a patented chemical reaction that breaks fluorine-carbon bonds and disassembles PFAS molecules in a linear fashion beginning with the [[Wikipedia: Hydrophile | hydrophilic]] functional groups and proceeding through shorter molecules to complete mineralization. Figure 1 shows how PRD is facilitated by adding [[Wikipedia: Cetrimonium bromide | cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)]] to form a surfactant micelle cage that traps PFAS. A non-toxic proprietary chemical is added to solution to associate with the micelle surface and produce hydrated electrons via stimulation with UV light. These highly reactive hydrated electrons have the energy required to cleave fluorine-carbon and other molecular bonds resulting in the final products of fluoride, water, and simple carbon molecules (e.g., formic acid and acetic acid). The methods, mechanisms, theory, and reactions described herein have been published in peer reviewed literature<ref name="ChenEtAl2020"/><ref name="TianEtAl2016"/><ref name="ChenEtAl2019"/><ref name="WittEtAl2023"/>. | ||

| − | + | ==Advantages and Disadvantages== | |

| − | == | + | ===Advantages=== |

| − | In the | + | In comparison to other reported PFAS destruction techniques, PRD offers several advantages: |

| + | *Relative to UV/sodium sulfite and UV/sodium iodide systems, the fitted degradation rates in the micelle-accelerated PRD reaction system were ~18 and ~36 times higher, indicating the key role of the self-assembled micelle in creating a confined space for rapid PFAS destruction<ref name="ChenEtAl2020"/>. The negatively charged hydrated electron associated with the positively charged cetyltrimethylammonium ion (CTA<sup>+</sup>) forms the surfactant micelle to trap molecules with similar structures, selectively mineralizing compounds with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups (e.g., PFAS). | ||

| + | *The PRD reaction does not require solid catalysts or electrodes, which can be expensive to acquire and difficult to regenerate or dispose. | ||

| + | *The aqueous solution is not heated or pressurized, and the UV wavelength used does not cause direct water [[Wikipedia: Photodissociation | photolysis]], therefore the energy input to the system is more directly employed to destroy PFAS, resulting in greater energy efficiency. | ||

| + | *Since the reaction is performed at ambient temperature and pressure, there are limited concerns regarding environmental health and safety or volatilization of PFAS compared to heated and pressurized systems. | ||

| + | *Due to the reductive nature of the reaction, there is no formation of unwanted byproducts resulting from oxidative processes, such as [[Wikipedia: Perchlorate | perchlorate]] generation during electrochemical oxidation<ref>Veciana, M., Bräunig, J., Farhat, A., Pype, M. L., Freguia, S., Carvalho, G., Keller, J., Ledezma, P., 2022. Electrochemical Oxidation Processes for PFAS Removal from Contaminated Water and Wastewater: Fundamentals, Gaps and Opportunities towards Practical Implementation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 434, Article 128886. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886]</ref><ref>Trojanowicz, M., Bojanowska-Czajka, A., Bartosiewicz, I., Kulisa, K., 2018. Advanced Oxidation/Reduction Processes Treatment for Aqueous Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) – A Review of Recent Advances. Chemical Engineering Journal, 336, pp. 170–199. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.153 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.153]</ref><ref>Wanninayake, D.M., 2021. Comparison of Currently Available PFAS Remediation Technologies in Water: A Review. Journal of Environmental Management, 283, Article 111977. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111977 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111977]</ref>. | ||

| + | *Aqueous fluoride ions are the primary end products of PRD, enabling real-time reaction monitoring with a fluoride [[Wikipedia: Ion-selective electrode | ion selective electrode (ISE)]], which is far less expensive and faster than relying on PFAS analytical data alone to monitor system performance. | ||

| − | The | + | ===Disadvantages=== |

| + | *The CTAB additive is only partially consumed during the reaction, and although CTAB is not problematic when discharged to downstream treatment processes that incorporate aerobic digestors, CTAB can be toxic to surface waters and anaerobic digestors. Therefore, disposal options for treated solutions will need to be evaluated on a site-specific basis. Possible options include removal of CTAB from solution for reuse in subsequent PRD treatments, or implementation of an oxidation reaction to degrade CTAB. | ||

| + | *The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS). It is hypothesized that in high TDS solutions (e.g., ion exchange still bottoms with TDS of 200,000 ppm), the presence of ionic species inhibits the association of the electron donor with the micelle, thus decreasing the reaction rate. | ||

| + | *The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with very low UV transmissivity. Low UV transmissivity (i.e., < 1 %) prevents the penetration of UV light into the solution, such that the utilization efficiency of UV light decreases. | ||

| − | == | + | ==State of the Art== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Technical Performance=== | |

| + | [[File:WittFig2.png | thumb |400px| Figure 2. Enspired Solutions<small><sup>TM</sup></small> commercial PRD PFAS destruction equipment, the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small>. Dimensions are 8 feet long by 4 feet wide by 9 feet tall.]] | ||

| − | + | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" | |

| − | + | |+Table 1. Percent decreases from initial PFAS concentrations during benchtop testing of PRD treatment in different water matrices | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:left; margin-right: | ||

| − | |+ Table 1. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! Analytes |

| − | ! | + | ! |

| − | ! | + | ! GW |

| − | ! | + | ! FF |

| − | ! | + | ! AFFF<br>Rinsate |

| + | ! AFF<br>(diluted 10X) | ||

| + | ! IDW NF | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ Total PFAS<small><sup>a</sup></small> (ND=0) |

| + | | rowspan="9" style="background-color:white;" | <p style="writing-mode: vertical-rl">% Decrease<br>(Initial Concentration, μg/L)</p> | ||

| + | | 93%<br>(370) || 96%<br>(32,000) || 89%<br>(57,000) || 86 %<br>(770,000) || 84%<br>(82) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ Total PFAS (ND=MDL) || 93%<br>(400) || 86%<br>(32,000) || 90%<br>(59,000) || 71%<br>(770,000) || 88%<br>(110) |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Σ Total PFAS (ND=RL) || 94%<br>(460) || 96%<br>(32,000) || 91%<br>(66,000) || 34%<br>(770,000) || 92%<br>(170) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ Highly Regulated PFAS<small><sup>b</sup></small> (ND=0) || >99%<br>(180) || >99%<br>(20,000) || 95%<br>(20,000) || 92%<br>(390,000) || 95%<br>(50) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=MDL) || >99%<br>(180) || 98%<br>(20,000) || 95%<br>(20,000) || 88%<br>(390,000) || 95%<br> (52) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=RL) || >99%<br>(190) || 93%<br>(20,000) || 95%<br>(20,000) || 79%<br>(390,000) || 95%<br>(55) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ High Priority PFAS<small><sup>c</sup></small> (ND=0) || 91%<br>(180) || 98%<br>(20,000) || 85%<br>(20,000) || 82%<br>(400,000) || 94%<br>(53) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=MDL) || 91%<br>(190) || 94%<br>(20,000) || 85%<br>(20,000) || 79%<br>(400,000) || 86%<br>(58) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=RL) || 92%<br>(200) || 87%<br>(20,000) || 86%<br>(21,000) || 70%<br>(400,000) || 87%<br>(65) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Fluorine mass balance<small><sup>d</sup></small> || ||106% || 109% || 110% || 65% || 98% |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Sorbed organic fluorine<small><sup>e</sup></small> || || 4% || 4% || 33% || N/A || 31% |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | colspan=" | + | | colspan="7" style="background-color:white; text-align:left" | <small>Notes:<br>GW = groundwater<br>GW FF = groundwater foam fractionate<br>AFFF rinsate = rinsate collected from fire system decontamination<br>AFFF (diluted 10x) = 3M Lightwater AFFF diluted 10x<br>IDW NF = investigation derived waste nanofiltrate<br>ND = non-detect<br>MDL = Method Detection Limit<br>RL = Reporting Limit<br><small><sup>a</sup></small>Total PFAS = 40 analytes + unidentified PFCA precursors<br><small><sup>b</sup></small>Highly regulated PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA<br><small><sup>c</sup></small>High priority PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFHxA, PFBA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA<br><small><sup>d</sup></small>Ratio of the final to the initial organic fluorine plus inorganic fluoride concentrations<br><small><sup>e</sup></small>Percent of organic fluorine that sorbed to the reactor walls during treatment<br></small> |

|} | |} | ||

| + | </br> | ||

| + | The PRD reaction has been validated at the bench scale for the destruction of PFAS in a variety of environmental samples from Department of Defense sites (Table 1). Enspired Solutions<small><sup>TM</sup></small> has designed and manufactured a fully automatic commercial-scale piece of equipment called PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small>, specializing in PRD PFAS destruction (Figure 2). This equipment is modular and scalable, has a small footprint, and can be used alone or in series with existing water treatment trains. The PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> employs commercially available UV reactors and monitoring meters that have been used in the water industry for decades. The system has been tested on PRD efficiency operational parameters, and key metrics were proven to be consistent with benchtop studies. | ||

| − | + | Bench scale PRD tests were performed for the following samples collected from Department of Defense sites: groundwater (GW), groundwater foam fractionate (FF), firefighting truck rinsate ([[Wikipedia: Firefighting foam | AFFF]] Rinsate), 3M Lightwater AFFF, investigation derived waste nanofiltrate (IDW NF), [[Wikipedia: Ion exchange | ion exchange]] still bottom (IX SB), and Ansulite AFFF. The PRD treatment was more effective in low conductivity/TDS solutions. Generally, PRD reaction rates decrease for solutions with a TDS > 10,000 ppm, with an upper limit of 30,000 ppm. Ansulite AFFF and IX SB samples showed low destruction efficiencies during initial screening tests, which was primarily attributed to their high TDS concentrations. Benchtop testing data are shown in Table 1 for the remaining five sample matrices. | |

| − | + | During treatment, PFOS and PFOA concentrations decreased 96% to >99% and 77% to 97%, respectively. For the PFAS with proposed drinking water Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) recently established by the USEPA (PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, and HFPO-DA), concentrations decreased >99% for GW, 93% for FF, 95% for AFFF Rinsate and IDW NF, and 79% for AFFF (diluted 10x) during the treatment time allotted. Meanwhile, the total PFAS concentrations, including all 40 known PFAS analytes and unidentified perfluorocarboxylic acid (PFCA) precursors, decreased from 34% to 96% following treatment. All of these concentration reduction values were calculated by using reporting limits (RL) as the concentrations for non-detects. | |

| − | |||

| − | There | + | Excellent fluorine/fluoride mass balance was achieved. There was nearly a 1:1 conversion of organic fluorine to free inorganic fluoride ion during treatment of GW, FF and AFFF Rinsate. The 3M Lightwater AFFF (diluted 10x) achieved only 65% fluorine mass balance, but this was likely due to high adsorption of PFAS to the reactor. |

| − | + | ===Application=== | |

| + | Due to the first-order kinetics of PRD, destruction of PFAS is most energy efficient when paired with a pre-concentration technology, such as foam fractionation (FF), nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, or resin/carbon adsorption, that remove PFAS from water. Application of the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> is therefore proposed as a part of a PFAS treatment train that includes a pre-concentration step. | ||

| − | The | + | The first pilot study with the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> was conducted in late 2023 at an industrial facility in Michigan with PFAS-impacted groundwater. The goal of the pilot study was to treat the groundwater to below the limits for regulatory discharge permits. For the pilot demonstration, the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> was paired with an FF unit, which pre-concentrated the PFAS into a foamate that was pumped into the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> for batch PFAS destruction. Residual PFAS remaining after the destruction batch was treated by looping back the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> effluent to the FF system influent. During the one-month field pilot duration, site-specific discharge limits were met, and steady state operation between the FF unit and PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> was achieved such that the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> destroyed the required concentrated PFAS mass and no off-site disposal of PFAS contaminated waste was required. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Latest revision as of 18:43, 8 May 2024

Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination PFAS Destruction

Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination (PRD) is a PFAS destruction technology predicated on ultraviolet (UV) light-activated photochemical reactions. The destruction efficiency of this process is enhanced by the use of a surfactant to confine PFAS molecules in self-assembled micelles. The photochemical reaction produces hydrated electrons from an electron donor that associates with the micelle. The hydrated electrons have sufficient energy to rapidly cleave fluorine-carbon and other molecular bonds of PFAS molecules due to the association of the electron donor with the micelle. Micelle-accelerated PRD is a highly efficient method to destroy PFAS in a wide variety of water matrices.

Related Article(s):

- Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Transport and Fate

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

Contributor(s):

- Dr. Suzanne Witt

- Dr. Meng Wang

- Dr. Denise Kay

Key Resource(s):

- Efficient Reductive Destruction of Perfluoroalkyl Substances under Self-Assembled Micelle Confinement[1]

- Complete Defluorination of Perfluorinated Compounds by Hydrated Electrons Generated from 3-Indole-Acetic-Acid in Organomodified Montmorillonite[2]

- Application of Surfactant Modified Montmorillonite with Different Conformation for Photo-Treatment of Perfluorooctanoic Acid by Hydrated Electrons[3]

- ER21-7569: Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination PFAS Destruction[4]

Introduction

The Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination (PRD) process is based on a patented chemical reaction that breaks fluorine-carbon bonds and disassembles PFAS molecules in a linear fashion beginning with the hydrophilic functional groups and proceeding through shorter molecules to complete mineralization. Figure 1 shows how PRD is facilitated by adding cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) to form a surfactant micelle cage that traps PFAS. A non-toxic proprietary chemical is added to solution to associate with the micelle surface and produce hydrated electrons via stimulation with UV light. These highly reactive hydrated electrons have the energy required to cleave fluorine-carbon and other molecular bonds resulting in the final products of fluoride, water, and simple carbon molecules (e.g., formic acid and acetic acid). The methods, mechanisms, theory, and reactions described herein have been published in peer reviewed literature[1][2][3][4].

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages

In comparison to other reported PFAS destruction techniques, PRD offers several advantages:

- Relative to UV/sodium sulfite and UV/sodium iodide systems, the fitted degradation rates in the micelle-accelerated PRD reaction system were ~18 and ~36 times higher, indicating the key role of the self-assembled micelle in creating a confined space for rapid PFAS destruction[1]. The negatively charged hydrated electron associated with the positively charged cetyltrimethylammonium ion (CTA+) forms the surfactant micelle to trap molecules with similar structures, selectively mineralizing compounds with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups (e.g., PFAS).

- The PRD reaction does not require solid catalysts or electrodes, which can be expensive to acquire and difficult to regenerate or dispose.

- The aqueous solution is not heated or pressurized, and the UV wavelength used does not cause direct water photolysis, therefore the energy input to the system is more directly employed to destroy PFAS, resulting in greater energy efficiency.

- Since the reaction is performed at ambient temperature and pressure, there are limited concerns regarding environmental health and safety or volatilization of PFAS compared to heated and pressurized systems.

- Due to the reductive nature of the reaction, there is no formation of unwanted byproducts resulting from oxidative processes, such as perchlorate generation during electrochemical oxidation[5][6][7].

- Aqueous fluoride ions are the primary end products of PRD, enabling real-time reaction monitoring with a fluoride ion selective electrode (ISE), which is far less expensive and faster than relying on PFAS analytical data alone to monitor system performance.

Disadvantages

- The CTAB additive is only partially consumed during the reaction, and although CTAB is not problematic when discharged to downstream treatment processes that incorporate aerobic digestors, CTAB can be toxic to surface waters and anaerobic digestors. Therefore, disposal options for treated solutions will need to be evaluated on a site-specific basis. Possible options include removal of CTAB from solution for reuse in subsequent PRD treatments, or implementation of an oxidation reaction to degrade CTAB.

- The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS). It is hypothesized that in high TDS solutions (e.g., ion exchange still bottoms with TDS of 200,000 ppm), the presence of ionic species inhibits the association of the electron donor with the micelle, thus decreasing the reaction rate.

- The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with very low UV transmissivity. Low UV transmissivity (i.e., < 1 %) prevents the penetration of UV light into the solution, such that the utilization efficiency of UV light decreases.

State of the Art

Technical Performance

| Analytes | GW | FF | AFFF Rinsate |

AFF (diluted 10X) |

IDW NF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Σ Total PFASa (ND=0) | % Decrease |

93% (370) |

96% (32,000) |

89% (57,000) |

86 % (770,000) |

84% (82) |

| Σ Total PFAS (ND=MDL) | 93% (400) |

86% (32,000) |

90% (59,000) |

71% (770,000) |

88% (110) | |

| Σ Total PFAS (ND=RL) | 94% (460) |

96% (32,000) |

91% (66,000) |

34% (770,000) |

92% (170) | |

| Σ Highly Regulated PFASb (ND=0) | >99% (180) |

>99% (20,000) |

95% (20,000) |

92% (390,000) |

95% (50) | |

| Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=MDL) | >99% (180) |

98% (20,000) |

95% (20,000) |

88% (390,000) |

95% (52) | |

| Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=RL) | >99% (190) |

93% (20,000) |

95% (20,000) |

79% (390,000) |

95% (55) | |

| Σ High Priority PFASc (ND=0) | 91% (180) |

98% (20,000) |

85% (20,000) |

82% (400,000) |

94% (53) | |

| Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=MDL) | 91% (190) |

94% (20,000) |

85% (20,000) |

79% (400,000) |

86% (58) | |

| Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=RL) | 92% (200) |

87% (20,000) |

86% (21,000) |

70% (400,000) |

87% (65) | |

| Fluorine mass balanced | 106% | 109% | 110% | 65% | 98% | |

| Sorbed organic fluorinee | 4% | 4% | 33% | N/A | 31% | |

| Notes: GW = groundwater GW FF = groundwater foam fractionate AFFF rinsate = rinsate collected from fire system decontamination AFFF (diluted 10x) = 3M Lightwater AFFF diluted 10x IDW NF = investigation derived waste nanofiltrate ND = non-detect MDL = Method Detection Limit RL = Reporting Limit aTotal PFAS = 40 analytes + unidentified PFCA precursors bHighly regulated PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA cHigh priority PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFHxA, PFBA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA dRatio of the final to the initial organic fluorine plus inorganic fluoride concentrations ePercent of organic fluorine that sorbed to the reactor walls during treatment | ||||||

The PRD reaction has been validated at the bench scale for the destruction of PFAS in a variety of environmental samples from Department of Defense sites (Table 1). Enspired SolutionsTM has designed and manufactured a fully automatic commercial-scale piece of equipment called PFASigatorTM, specializing in PRD PFAS destruction (Figure 2). This equipment is modular and scalable, has a small footprint, and can be used alone or in series with existing water treatment trains. The PFASigatorTM employs commercially available UV reactors and monitoring meters that have been used in the water industry for decades. The system has been tested on PRD efficiency operational parameters, and key metrics were proven to be consistent with benchtop studies.

Bench scale PRD tests were performed for the following samples collected from Department of Defense sites: groundwater (GW), groundwater foam fractionate (FF), firefighting truck rinsate ( AFFF Rinsate), 3M Lightwater AFFF, investigation derived waste nanofiltrate (IDW NF), ion exchange still bottom (IX SB), and Ansulite AFFF. The PRD treatment was more effective in low conductivity/TDS solutions. Generally, PRD reaction rates decrease for solutions with a TDS > 10,000 ppm, with an upper limit of 30,000 ppm. Ansulite AFFF and IX SB samples showed low destruction efficiencies during initial screening tests, which was primarily attributed to their high TDS concentrations. Benchtop testing data are shown in Table 1 for the remaining five sample matrices.

During treatment, PFOS and PFOA concentrations decreased 96% to >99% and 77% to 97%, respectively. For the PFAS with proposed drinking water Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) recently established by the USEPA (PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, and HFPO-DA), concentrations decreased >99% for GW, 93% for FF, 95% for AFFF Rinsate and IDW NF, and 79% for AFFF (diluted 10x) during the treatment time allotted. Meanwhile, the total PFAS concentrations, including all 40 known PFAS analytes and unidentified perfluorocarboxylic acid (PFCA) precursors, decreased from 34% to 96% following treatment. All of these concentration reduction values were calculated by using reporting limits (RL) as the concentrations for non-detects.

Excellent fluorine/fluoride mass balance was achieved. There was nearly a 1:1 conversion of organic fluorine to free inorganic fluoride ion during treatment of GW, FF and AFFF Rinsate. The 3M Lightwater AFFF (diluted 10x) achieved only 65% fluorine mass balance, but this was likely due to high adsorption of PFAS to the reactor.

Application

Due to the first-order kinetics of PRD, destruction of PFAS is most energy efficient when paired with a pre-concentration technology, such as foam fractionation (FF), nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, or resin/carbon adsorption, that remove PFAS from water. Application of the PFASigatorTM is therefore proposed as a part of a PFAS treatment train that includes a pre-concentration step.

The first pilot study with the PFASigatorTM was conducted in late 2023 at an industrial facility in Michigan with PFAS-impacted groundwater. The goal of the pilot study was to treat the groundwater to below the limits for regulatory discharge permits. For the pilot demonstration, the PFASigatorTM was paired with an FF unit, which pre-concentrated the PFAS into a foamate that was pumped into the PFASigatorTM for batch PFAS destruction. Residual PFAS remaining after the destruction batch was treated by looping back the PFASigatorTM effluent to the FF system influent. During the one-month field pilot duration, site-specific discharge limits were met, and steady state operation between the FF unit and PFASigatorTM was achieved such that the PFASigatorTM destroyed the required concentrated PFAS mass and no off-site disposal of PFAS contaminated waste was required.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Chen, Z., Li, C., Gao, J., Dong, H., Chen, Y., Wu, B., Gu, C., 2020. Efficient Reductive Destruction of Perfluoroalkyl Substances under Self-Assembled Micelle Confinement. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(8), pp. 5178–5185. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b06599

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Tian, H., Gao, J., Li, H., Boyd, S.A., Gu, C., 2016. Complete Defluorination of Perfluorinated Compounds by Hydrated Electrons Generated from 3-Indole-Acetic-Acid in Organomodified Montmorillonite. Scientific Reports, 6(1), Article 32949. doi: 10.1038/srep32949 Open Access Article

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Chen, Z., Tian, H., Li, H., Li, J. S., Hong, R., Sheng, F., Wang, C., Gu, C., 2019. Application of Surfactant Modified Montmorillonite with Different Conformation for Photo-Treatment of Perfluorooctanoic Acid by Hydrated Electrons. Chemosphere, 235, pp. 1180–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.032

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kay, D., Witt, S., Wang, M., 2023. Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination PFAS Destruction: Final Report. ESTCP Project ER21-7569. Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ Veciana, M., Bräunig, J., Farhat, A., Pype, M. L., Freguia, S., Carvalho, G., Keller, J., Ledezma, P., 2022. Electrochemical Oxidation Processes for PFAS Removal from Contaminated Water and Wastewater: Fundamentals, Gaps and Opportunities towards Practical Implementation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 434, Article 128886. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886

- ^ Trojanowicz, M., Bojanowska-Czajka, A., Bartosiewicz, I., Kulisa, K., 2018. Advanced Oxidation/Reduction Processes Treatment for Aqueous Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) – A Review of Recent Advances. Chemical Engineering Journal, 336, pp. 170–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.153

- ^ Wanninayake, D.M., 2021. Comparison of Currently Available PFAS Remediation Technologies in Water: A Review. Journal of Environmental Management, 283, Article 111977. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111977