Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Thermodynamics of PFAS Accumulations on Solid Surfaces) |

(→Introduction) |

||

| (84 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange== |

| − | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)| | + | [[Wikipedia: Ion exchange | Anion exchange]] has emerged as one of the most effective and economical technologies for treatment of water contaminated by [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)]]. Anion exchange resins (AERs) are polymer beads (0.5–1 mm diameter) incorporating cationic adsorption sites that attract anionic PFAS by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic mechanisms. Both regenerable and single-use resin treatment systems are being investigated, and results from pilot-scale studies show that AERs can treat much greater volumes of PFAS-contaminated water than comparable amounts of [[Wikipedia: Activated carbon | granular activated carbon (GAC)]] adsorbent media. Life cycle treatment costs and environmental impacts of anion exchange and other adsorbent technologies are highly dependent upon the treatment criteria selected by site managers to determine when media is exhausted and requires replacement or regeneration. |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

*[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] | ||

*[[PFAS Sources]] | *[[PFAS Sources]] | ||

| + | *[[PFAS Transport and Fate]] | ||

*[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] | ||

*[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] | ||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

'''Contributor(s):''' | '''Contributor(s):''' | ||

| − | *Dr. | + | *Dr. Timothy J. Strathmann |

| − | *Dr. | + | *Dr. Anderson Ellis |

| − | + | *Dr. Treavor H. Boyer | |

| − | *Dr. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''Key Resource(s):''' | '''Key Resource(s):''' | ||

| − | * | + | *Anion Exchange Resin Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Impacted Water: A Critical Review<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021a">Boyer, T.H., Fang, Y., Ellis, A., Dietz, R., Choi, Y.J., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Anion Exchange Resin Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Impacted Water: A Critical Review. Water Research, 200, Article 117244. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.117244 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117244] [[Media: BoyerEtAl2021a.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref> |

| − | *[[Media: | + | |

| + | *Regenerable Resin Sorbent Technologies with Regenerant Solution Recycling for Sustainable Treatment of PFAS; SERDP Project ER18-1063 Final Report<ref>Strathmann, T.J., Higgins, C.P., Boyer, T., Schaefer, C., Ellis, A., Fang, Y., del Moral, L., Dietz, R., Kassar, C., Graham, C, 2023. Regenerable Resin Sorbent Technologies with Regenerant Solution Recycling for Sustainable Treatment of PFAS; SERDP Project ER18-1063 Final Report. 285 pages. [https://serdp-estcp.org/projects/details/d3ede38b-9f24-4b22-91c9-1ad634aa5384 Project Website] [[Media: ER18-1063.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

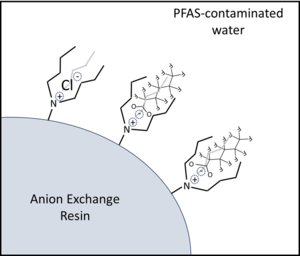

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:StrathmannFig1.png | thumb |300px|Figure 1. Illustration of PFAS adsorption by anion exchange resins (AERs). Incorporation of longer alkyl group side chains on the cationic quaternary amine functional groups leads to PFAS-resin hydrophobic interactions that increase resin selectivity for PFAS over inorganic anions like Cl<sup>-</sup>.]] |

| − | + | [[File:StrathmannFig2.png | thumb | left |300px|Figure 2. Effect of perfluoroalkyl carbon chain length on the estimated bed volumes (BVs) to 50% breakthrough of PFCAs and PFSAs observed in a pilot study<ref name="EllisEtAl2022/"> treating PFAS-contaminated groundwater with the PFAS-selective AER (Purolite PFA694E)]] | |

| − | + | Anion exchange is an adsorptive treatment technology that uses polymeric resin beads (0.5–1 mm diameter) that incorporate cationic adsorption sites to remove anionic pollutants from water<ref>SenGupta, A.K., 2017. Ion Exchange in Environmental Processes: Fundamentals, Applications and Sustainable Technology. Wiley. ISBN:9781119157397 [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119421252 Wiley Online Library]</ref>. Anions (e.g., NO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup>) are adsorbed by an ion exchange reaction with anions that are initially bound to the adsorption sites (e.g., Cl<sup>-</sup>) during resin preparation. Many per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) of concern, including [[Wikipedia: Perfluorooctanoic acid | perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)]], are present in contaminated water as anionic species that can be adsorbed by anion exchange reactions<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021a"/><ref name="DixitEtAl2021">Dixit, F., Dutta, R., Barbeau, B., Berube, P., Mohseni, M., 2021. PFAS Removal by Ion Exchange Resins: A Review. Chemosphere, 272, Article 129777. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129777 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129777]</ref><ref name="RahmanEtAl2014">Rahman, M.F., Peldszus, S., Anderson, W.B., 2014. Behaviour and Fate of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Drinking Water Treatment: A Review. Water Research, 50, pp. 318–340. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.045 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.045]</ref>. | |

| − | [[ | + | </br> |

| + | <center><big>Anion Exchange Reaction: '''PFAS<sup>-</sup></big><sub>(aq)</sub><big> + Cl<sup>-</sup></big><sub>(resin bound)</sub><big> ⇒ PFAS<sup>-</sup></big><sub>(resin bound)</sub><big> + Cl<sup>-</sup></big><sub>(aq)</sub>'''</center> | ||

| + | Resins most commonly applied for PFAS treatment are strong base anion exchange resins (SB-AERs) that incorporate [[Wikipedia: Quaternary ammonium cation | quaternary ammonium]] cationic functional groups with hydrocarbon side chains (R-groups) that promote PFAS adsorption by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic mechanisms (Figure 1)<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021a"/><ref>Fuller, Mark. Ex Situ Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Groundwater Using Ion Exchange with Regeneration; ER18-1027. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/af660326-56e0-4d3c-b80a-1d8a2d613724 Project Website].</ref>. SB-AERs maintain cationic functional groups independent of water pH. Recently introduced ‘PFAS-selective’ AERs show >1,000,000-fold greater selectivity for some PFAS over the Cl<sup>-</sup> initially loaded onto resins<ref name="FangEtAl2021">Fang, Y., Ellis, A., Choi, Y.J., Boyer, T.H., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) Using Ion-Exchange and Nonionic Resins. Environmental Science and Technology, 55(8), pp. 5001–5011. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c00769 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00769]</ref>. These resins also show much higher adsorption capacities for PFAS (mg PFAS adsorbed per gram of adsorbent media) than granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbents. | ||

| + | |||

| + | PFAS of concern include a wide range of structures, including [[Wikipedia: Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids | perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorosulfonic acids | perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids (PFSAs)]] of varying carbon chain length<ref>Interstate Technology Regulatory Council (ITRC), 2023. Technical Resources for Addressing Environmental Releases of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). [https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/ ITRC PFAS Website]</ref>. As such, affinity for adsorption to AERs is heavily dependent upon PFAS structure<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021a"/><ref name="DixitEtAl2021"/>. In general, it has been found that the extent of adsorption increases with increasing chain length, and that PFSAs adsorb more strongly than PFCAs of similar chain length (Figure 2)<ref name="FangEtAl2021"/><ref>Gagliano, E., Sgroi, M., Falciglia, P.P., Vagliasindi, F.G.A., Roccaro, P., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Water by Adsorption: Role of PFAS Chain Length, Effect of Organic Matter and Challenges in Adsorbent Regeneration. Water Research, 171, Article 115381. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.115381 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115381]</ref>. The chain length-dependence supports the conclusion that PFAS-resin hydrophobic mechanisms contribute to adsorption. Adsorption of polyfluorinated structures also depend on structure and prevailing charge, with adsorption of zwitterionic species (containing both anionic and cationic groups in the same structure) to AERs being documented despite having a net neutral charge<ref name="FangEtAl2021"/>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Reactors for Treatment of PFAS-Contaminated Water== | ||

| + | Anion exchange treatment of water is accomplished by pumping contaminated water through fixed bed reactors filled with AERs (Figure 3). A common configuration involves flowing water through two reactors arranged in a lead-lag configuration<ref name="WoodardEtAl2017">Woodard, S., Berry, J., Newman, B., 2017. Ion Exchange Resin for PFAS Removal and Pilot Test Comparison to GAC. Remediation, 27(3), pp. 19–27. [https://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21515 doi: 10.1002/rem.21515]</ref>. Water flows through the pore spaces in close contact with resin beads. Sufficient contact time needs to be provided, referred to as empty bed contact time (EBCT), to allow PFAS to diffuse from the water into the resin structure and adsorb to exchange sites. Typical EBCTs for AER treatment of PFAS are 2-5 min, shorter than contact times recommended for granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbents (≥10 min)<ref name="LiuEtAl2022">Liu, C. J., Murray, C.C., Marshall, R.E., Strathmann, T.J., Bellona, C., 2022. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from Contaminated Groundwater by Granular Activated Carbon and Anion Exchange Resins: A Pilot-Scale Comparative Assessment. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 8(10), pp. 2245–2253. [https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EW00080F doi: 10.1039/D2EW00080F]</ref><ref>Liu, C.J., Werner, D., Bellona, C., 2019. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) from Contaminated Groundwater Using Granular Activated Carbon: A Pilot-Scale Study with Breakthrough Modeling. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 5(11), pp. 1844–1853. [https://doi.org/10.1039/C9EW00349E doi: 10.1039/C9EW00349E]</ref>. The higher adsorption capacities and shorter EBCTs of AERs enable use of much less media and smaller vessels than GAC, reducing expected capital costs for AER treatment systems<ref name="EllisEtAl2023">Ellis, A.C., Boyer, T.H., Fang, Y., Liu, C.J., Strathmann, T.J., 2023. Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Cost Analysis of Anion Exchange and Granular Activated Carbon Systems for Remediation of Groundwater Contaminated by Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Water Research, 243, Article 120324. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.120324 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.120324]</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Like other adsorption media, PFAS will initially adsorb to media encountered near the inlet side of the reactor, but as ion exchange sites become saturated with PFAS, the active zone of adsorption will begin to migrate through the packed bed with increasing volume of water treated. Moreover, some PFAS with lower affinity for exchange sites (e.g., shorter-chain PFAS that are less hydrophobic) will be displaced by competition from other PFAS (e.g., longer-chain PFAS that are more hydrophobic) and move further along the bed to occupy open sites<ref name="EllisEtAl2022">Ellis, A.C., Liu, C.J., Fang, Y., Boyer, T.H., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2022. Pilot Study Comparison of Regenerable and Emerging Single-Use Anion Exchange Resins for Treatment of Groundwater Contaminated by per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Water Research, 223, Article 119019. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.119019 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.119019] [[Media: EllisEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref>. Eventually, PFAS will start to breakthrough into the effluent from the reactor, typically beginning with the shorter-chain compounds. The initial breakthrough of shorter-chain PFAS is similar to the behavior observed for AER treatment of inorganic contaminants. | ||

| − | + | Upon breakthrough, treatment is halted, and the exhausted resins are either replaced with fresh media or regenerated before continuing treatment. Most vendors are currently operating AER treatment systems for PFAS in single-use mode where virgin media is delivered to replace exhausted resins, which are transported off-site for disposal or incineration<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021a"/>. As an alternative, some providers are developing regenerable AER treatment systems, where exhausted resins are regenerated on-site by desorbing PFAS from the resins using a combination of salt brine (typically ≥1 wt% NaCl) and cosolvent (typically ≥70 vol% methanol)<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021a"/><ref name="BoyerEtAl2021b">Boyer, T.H., Ellis, A., Fang, Y., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of Regeneration Options for Anion Exchange Resin Remediation of PFAS Impacted Water. Water Research, 207, Article 117798. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.117798 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117798] [[Media: BoyerEtAl2021b.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref><ref>Houtz, E., (projected completion 2025). Treatment of PFAS in Groundwater with Regenerable Anion Exchange Resin as a Bridge to PFAS Destruction, Project ER23-8391. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a12b603d-0d4a-4473-bf5b-069313a348ba/treatment-of-pfas-in-groundwater-with-regenerable-anion-exchange-resin-as-a-bridge-to-pfas-destruction Project Website].</ref>. This mode of operation allows for longer term use of resins before replacement, but requires more complex and extensive site infrastructure. Cosolvent in the resulting waste regenerant can be recycled by distillation, which reduces chemical inputs and lowers the volume of PFAS-contaminated still bottoms requiring further treatment or disposal<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021b"/>. Currently, there is active research on various technologies for destruction of PFAS concentrates in AER still bottoms residuals<ref name="StrathmannEtAl2020">Strathmann, T.J., Higgins, C., Deeb, R., 2020. Hydrothermal Technologies for On-Site Destruction of Site Investigation Wastes Impacted by PFAS, Final Report - Phase I. SERDP Project ER18-1501. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/b34d6396-6b6d-44d0-a89e-6b22522e6e9c Project Website] [[Media: ER18-1501.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="HuangEtAl2021">Huang, Q., Woodard, S., Nickleson, M., Chiang, D., Liang, S., Mora, R., 2021. Electrochemical Oxidation of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Still Bottoms from Regeneration of Ion Exchange Resins Phase I - Final Report. SERDP Project ER18-1320. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/ccaa70c4-b40a-4520-ba17-14db2cd98e8f Project Website] [[Media: ER18-1320.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. | |

| − | == | + | ==Field Demonstrations== |

| − | + | Field pilot studies are critical to demonstrating the effectiveness and expected costs of PFAS treatment technologies. A growing number of pilot studies testing the performance of commercially available AERs to treat PFAS-contaminated groundwater, including sites impacted by historical use of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), have been published recently (Figure 4) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In comparison to other reported PFAS destruction techniques, PRD offers several advantages: | |

| + | *Relative to UV/sodium sulfite and UV/sodium iodide systems, the fitted degradation rates in the micelle-accelerated PRD reaction system were ~18 and ~36 times higher, indicating the key role of the self-assembled micelle in creating a confined space for rapid PFAS destruction<ref name="ChenEtAl2020"/>. The negatively charged hydrated electron associated with the positively charged cetyltrimethylammonium ion (CTA<sup>+</sup>) forms the surfactant micelle to trap molecules with similar structures, selectively mineralizing compounds with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups (e.g., PFAS). | ||

| + | *The PRD reaction does not require solid catalysts or electrodes, which can be expensive to acquire and difficult to regenerate or dispose. | ||

| + | *The aqueous solution is not heated or pressurized, and the UV wavelength used does not cause direct water [[Wikipedia: Photodissociation | photolysis]], therefore the energy input to the system is more directly employed to destroy PFAS, resulting in greater energy efficiency. | ||

| + | *Since the reaction is performed at ambient temperature and pressure, there are limited concerns regarding environmental health and safety or volatilization of PFAS compared to heated and pressurized systems. | ||

| + | *Due to the reductive nature of the reaction, there is no formation of unwanted byproducts resulting from oxidative processes, such as [[Wikipedia: Perchlorate | perchlorate]] generation during electrochemical oxidation<ref>Veciana, M., Bräunig, J., Farhat, A., Pype, M. L., Freguia, S., Carvalho, G., Keller, J., Ledezma, P., 2022. Electrochemical Oxidation Processes for PFAS Removal from Contaminated Water and Wastewater: Fundamentals, Gaps and Opportunities towards Practical Implementation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 434, Article 128886. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886]</ref><ref>Trojanowicz, M., Bojanowska-Czajka, A., Bartosiewicz, I., Kulisa, K., 2018. Advanced Oxidation/Reduction Processes Treatment for Aqueous Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) – A Review of Recent Advances. Chemical Engineering Journal, 336, pp. 170–199. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.153 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.153]</ref><ref>Wanninayake, D.M., 2021. Comparison of Currently Available PFAS Remediation Technologies in Water: A Review. Journal of Environmental Management, 283, Article 111977. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111977 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111977]</ref>. | ||

| + | *Aqueous fluoride ions are the primary end products of PRD, enabling real-time reaction monitoring with a fluoride [[Wikipedia: Ion-selective electrode | ion selective electrode (ISE)]], which is far less expensive and faster than relying on PFAS analytical data alone to monitor system performance. | ||

| − | + | ===Disadvantages=== | |

| + | *The CTAB additive is only partially consumed during the reaction, and although CTAB is not problematic when discharged to downstream treatment processes that incorporate aerobic digestors, CTAB can be toxic to surface waters and anaerobic digestors. Therefore, disposal options for treated solutions will need to be evaluated on a site-specific basis. Possible options include removal of CTAB from solution for reuse in subsequent PRD treatments, or implementation of an oxidation reaction to degrade CTAB. | ||

| + | *The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS). It is hypothesized that in high TDS solutions (e.g., ion exchange still bottoms with TDS of 200,000 ppm), the presence of ionic species inhibits the association of the electron donor with the micelle, thus decreasing the reaction rate. | ||

| + | *The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with very low UV transmissivity. Low UV transmissivity (i.e., < 1 %) prevents the penetration of UV light into the solution, such that the utilization efficiency of UV light decreases. | ||

| − | == | + | ==State of the Art== |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Technical Performance=== | |

| + | [[File:WittFig2.png | thumb |400px| Figure 2. Enspired Solutions<small><sup>TM</sup></small> commercial PRD PFAS destruction equipment, the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small>. Dimensions are 8 feet long by 4 feet wide by 9 feet tall.]] | ||

{| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" | ||

| Line 58: | Line 73: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Σ Total PFAS<small><sup>a</sup></small> (ND=0) | | Σ Total PFAS<small><sup>a</sup></small> (ND=0) | ||

| − | | rowspan="9 | + | | rowspan="9" style="background-color:white;" | <p style="writing-mode: vertical-rl">% Decrease<br>(Initial Concentration, μg/L)</p> |

| − | | 93%<br>(370) || 96%<br>(32,000) || 89%<br>(57,000) || 86 %<br>(770,000) || 84% (82) | + | | 93%<br>(370) || 96%<br>(32,000) || 89%<br>(57,000) || 86 %<br>(770,000) || 84%<br>(82) |

|- | |- | ||

| Σ Total PFAS (ND=MDL) || 93%<br>(400) || 86%<br>(32,000) || 90%<br>(59,000) || 71%<br>(770,000) || 88%<br>(110) | | Σ Total PFAS (ND=MDL) || 93%<br>(400) || 86%<br>(32,000) || 90%<br>(59,000) || 71%<br>(770,000) || 88%<br>(110) | ||

| Line 71: | Line 86: | ||

| Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=RL) || >99%<br>(190) || 93%<br>(20,000) || 95%<br>(20,000) || 79%<br>(390,000) || 95%<br>(55) | | Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=RL) || >99%<br>(190) || 93%<br>(20,000) || 95%<br>(20,000) || 79%<br>(390,000) || 95%<br>(55) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Σ Priority PFAS<small><sup>c</sup></small> (ND=0) || 91%<br>(180) || 98%<br>(20,000) || 85%<br>(20,000) || 82%<br>(400,000) || 94%<br>(53) | + | | Σ High Priority PFAS<small><sup>c</sup></small> (ND=0) || 91%<br>(180) || 98%<br>(20,000) || 85%<br>(20,000) || 82%<br>(400,000) || 94%<br>(53) |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=MDL) || 91%<br>(190) || 94%<br>(20,000) || 85%<br>(20,000) || 79%<br>(400,000) || 86%<br>(58) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=RL) || 92%<br>(200) || 87%<br>(20,000) || 86%<br>(21,000) || 70%<br>(400,000) || 87%<br>(65) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Fluorine mass balance<small><sup>d</sup></small> || ||106% || 109% || 110% || 65% || 98% | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Sorbed organic fluorine<small><sup>e</sup></small> || || 4% || 4% || 33% || N/A || 31% |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | colspan="7" style="background-color:white; text-align:left" | <small>Notes:<br>GW = groundwater<br>GW FF = groundwater foam fractionate<br>AFFF rinsate = rinsate collected from fire system decontamination<br>AFFF (diluted 10x) = 3M Lightwater AFFF diluted 10x<br>IDW NF = investigation derived waste nanofiltrate<br>ND = non-detect<br>MDL = Method Detection Limit<br>RL = Reporting Limit<br><small><sup>a</sup></small>Total PFAS = 40 analytes + unidentified PFCA precursors<br><small><sup>b</sup></small>Highly regulated PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA<br><small><sup>c</sup></small>High priority PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFHxA, PFBA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA<br><small><sup>d</sup></small>Ratio of the final to the initial organic fluorine plus inorganic fluoride concentrations<br><small><sup>e</sup></small>Percent of organic fluorine that sorbed to the reactor walls during treatment<br></small> |

|} | |} | ||

| + | </br> | ||

| + | The PRD reaction has been validated at the bench scale for the destruction of PFAS in a variety of environmental samples from Department of Defense sites (Table 1). Enspired Solutions<small><sup>TM</sup></small> has designed and manufactured a fully automatic commercial-scale piece of equipment called PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small>, specializing in PRD PFAS destruction (Figure 2). This equipment is modular and scalable, has a small footprint, and can be used alone or in series with existing water treatment trains. The PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> employs commercially available UV reactors and monitoring meters that have been used in the water industry for decades. The system has been tested on PRD efficiency operational parameters, and key metrics were proven to be consistent with benchtop studies. | ||

| + | Bench scale PRD tests were performed for the following samples collected from Department of Defense sites: groundwater (GW), groundwater foam fractionate (FF), firefighting truck rinsate ([[Wikipedia: Firefighting foam | AFFF]] Rinsate), 3M Lightwater AFFF, investigation derived waste nanofiltrate (IDW NF), [[Wikipedia: Ion exchange | ion exchange]] still bottom (IX SB), and Ansulite AFFF. The PRD treatment was more effective in low conductivity/TDS solutions. Generally, PRD reaction rates decrease for solutions with a TDS > 10,000 ppm, with an upper limit of 30,000 ppm. Ansulite AFFF and IX SB samples showed low destruction efficiencies during initial screening tests, which was primarily attributed to their high TDS concentrations. Benchtop testing data are shown in Table 1 for the remaining five sample matrices. | ||

| − | + | During treatment, PFOS and PFOA concentrations decreased 96% to >99% and 77% to 97%, respectively. For the PFAS with proposed drinking water Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) recently established by the USEPA (PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, and HFPO-DA), concentrations decreased >99% for GW, 93% for FF, 95% for AFFF Rinsate and IDW NF, and 79% for AFFF (diluted 10x) during the treatment time allotted. Meanwhile, the total PFAS concentrations, including all 40 known PFAS analytes and unidentified perfluorocarboxylic acid (PFCA) precursors, decreased from 34% to 96% following treatment. All of these concentration reduction values were calculated by using reporting limits (RL) as the concentrations for non-detects. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Excellent fluorine/fluoride mass balance was achieved. There was nearly a 1:1 conversion of organic fluorine to free inorganic fluoride ion during treatment of GW, FF and AFFF Rinsate. The 3M Lightwater AFFF (diluted 10x) achieved only 65% fluorine mass balance, but this was likely due to high adsorption of PFAS to the reactor. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ===Application=== |

| − | + | Due to the first-order kinetics of PRD, destruction of PFAS is most energy efficient when paired with a pre-concentration technology, such as foam fractionation (FF), nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, or resin/carbon adsorption, that remove PFAS from water. Application of the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> is therefore proposed as a part of a PFAS treatment train that includes a pre-concentration step. | |

| − | + | The first pilot study with the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> was conducted in late 2023 at an industrial facility in Michigan with PFAS-impacted groundwater. The goal of the pilot study was to treat the groundwater to below the limits for regulatory discharge permits. For the pilot demonstration, the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> was paired with an FF unit, which pre-concentrated the PFAS into a foamate that was pumped into the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> for batch PFAS destruction. Residual PFAS remaining after the destruction batch was treated by looping back the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> effluent to the FF system influent. During the one-month field pilot duration, site-specific discharge limits were met, and steady state operation between the FF unit and PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> was achieved such that the PFASigator<small><sup>TM</sup></small> destroyed the required concentrated PFAS mass and no off-site disposal of PFAS contaminated waste was required. | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 108: | Line 116: | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 21:59, 16 May 2024

PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange

Anion exchange has emerged as one of the most effective and economical technologies for treatment of water contaminated by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Anion exchange resins (AERs) are polymer beads (0.5–1 mm diameter) incorporating cationic adsorption sites that attract anionic PFAS by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic mechanisms. Both regenerable and single-use resin treatment systems are being investigated, and results from pilot-scale studies show that AERs can treat much greater volumes of PFAS-contaminated water than comparable amounts of granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbent media. Life cycle treatment costs and environmental impacts of anion exchange and other adsorbent technologies are highly dependent upon the treatment criteria selected by site managers to determine when media is exhausted and requires replacement or regeneration.

Related Article(s):

- Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Transport and Fate

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

Contributor(s):

- Dr. Timothy J. Strathmann

- Dr. Anderson Ellis

- Dr. Treavor H. Boyer

Key Resource(s):

- Anion Exchange Resin Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Impacted Water: A Critical Review[1]

- Regenerable Resin Sorbent Technologies with Regenerant Solution Recycling for Sustainable Treatment of PFAS; SERDP Project ER18-1063 Final Report[2]

Introduction

[[File:StrathmannFig2.png | thumb | left |300px|Figure 2. Effect of perfluoroalkyl carbon chain length on the estimated bed volumes (BVs) to 50% breakthrough of PFCAs and PFSAs observed in a pilot studyCite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag. Anions (e.g., NO3-) are adsorbed by an ion exchange reaction with anions that are initially bound to the adsorption sites (e.g., Cl-) during resin preparation. Many per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) of concern, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), are present in contaminated water as anionic species that can be adsorbed by anion exchange reactions[1][3][4].

Resins most commonly applied for PFAS treatment are strong base anion exchange resins (SB-AERs) that incorporate quaternary ammonium cationic functional groups with hydrocarbon side chains (R-groups) that promote PFAS adsorption by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic mechanisms (Figure 1)[1][5]. SB-AERs maintain cationic functional groups independent of water pH. Recently introduced ‘PFAS-selective’ AERs show >1,000,000-fold greater selectivity for some PFAS over the Cl- initially loaded onto resins[6]. These resins also show much higher adsorption capacities for PFAS (mg PFAS adsorbed per gram of adsorbent media) than granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbents.

PFAS of concern include a wide range of structures, including perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) and perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids (PFSAs) of varying carbon chain length[7]. As such, affinity for adsorption to AERs is heavily dependent upon PFAS structure[1][3]. In general, it has been found that the extent of adsorption increases with increasing chain length, and that PFSAs adsorb more strongly than PFCAs of similar chain length (Figure 2)[6][8]. The chain length-dependence supports the conclusion that PFAS-resin hydrophobic mechanisms contribute to adsorption. Adsorption of polyfluorinated structures also depend on structure and prevailing charge, with adsorption of zwitterionic species (containing both anionic and cationic groups in the same structure) to AERs being documented despite having a net neutral charge[6].

Reactors for Treatment of PFAS-Contaminated Water

Anion exchange treatment of water is accomplished by pumping contaminated water through fixed bed reactors filled with AERs (Figure 3). A common configuration involves flowing water through two reactors arranged in a lead-lag configuration[9]. Water flows through the pore spaces in close contact with resin beads. Sufficient contact time needs to be provided, referred to as empty bed contact time (EBCT), to allow PFAS to diffuse from the water into the resin structure and adsorb to exchange sites. Typical EBCTs for AER treatment of PFAS are 2-5 min, shorter than contact times recommended for granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbents (≥10 min)[10][11]. The higher adsorption capacities and shorter EBCTs of AERs enable use of much less media and smaller vessels than GAC, reducing expected capital costs for AER treatment systems[12].

Like other adsorption media, PFAS will initially adsorb to media encountered near the inlet side of the reactor, but as ion exchange sites become saturated with PFAS, the active zone of adsorption will begin to migrate through the packed bed with increasing volume of water treated. Moreover, some PFAS with lower affinity for exchange sites (e.g., shorter-chain PFAS that are less hydrophobic) will be displaced by competition from other PFAS (e.g., longer-chain PFAS that are more hydrophobic) and move further along the bed to occupy open sites[13]. Eventually, PFAS will start to breakthrough into the effluent from the reactor, typically beginning with the shorter-chain compounds. The initial breakthrough of shorter-chain PFAS is similar to the behavior observed for AER treatment of inorganic contaminants.

Upon breakthrough, treatment is halted, and the exhausted resins are either replaced with fresh media or regenerated before continuing treatment. Most vendors are currently operating AER treatment systems for PFAS in single-use mode where virgin media is delivered to replace exhausted resins, which are transported off-site for disposal or incineration[1]. As an alternative, some providers are developing regenerable AER treatment systems, where exhausted resins are regenerated on-site by desorbing PFAS from the resins using a combination of salt brine (typically ≥1 wt% NaCl) and cosolvent (typically ≥70 vol% methanol)[1][14][15]. This mode of operation allows for longer term use of resins before replacement, but requires more complex and extensive site infrastructure. Cosolvent in the resulting waste regenerant can be recycled by distillation, which reduces chemical inputs and lowers the volume of PFAS-contaminated still bottoms requiring further treatment or disposal[14]. Currently, there is active research on various technologies for destruction of PFAS concentrates in AER still bottoms residuals[16][17].

Field Demonstrations

Field pilot studies are critical to demonstrating the effectiveness and expected costs of PFAS treatment technologies. A growing number of pilot studies testing the performance of commercially available AERs to treat PFAS-contaminated groundwater, including sites impacted by historical use of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), have been published recently (Figure 4)

In comparison to other reported PFAS destruction techniques, PRD offers several advantages:

- Relative to UV/sodium sulfite and UV/sodium iodide systems, the fitted degradation rates in the micelle-accelerated PRD reaction system were ~18 and ~36 times higher, indicating the key role of the self-assembled micelle in creating a confined space for rapid PFAS destruction[18]. The negatively charged hydrated electron associated with the positively charged cetyltrimethylammonium ion (CTA+) forms the surfactant micelle to trap molecules with similar structures, selectively mineralizing compounds with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups (e.g., PFAS).

- The PRD reaction does not require solid catalysts or electrodes, which can be expensive to acquire and difficult to regenerate or dispose.

- The aqueous solution is not heated or pressurized, and the UV wavelength used does not cause direct water photolysis, therefore the energy input to the system is more directly employed to destroy PFAS, resulting in greater energy efficiency.

- Since the reaction is performed at ambient temperature and pressure, there are limited concerns regarding environmental health and safety or volatilization of PFAS compared to heated and pressurized systems.

- Due to the reductive nature of the reaction, there is no formation of unwanted byproducts resulting from oxidative processes, such as perchlorate generation during electrochemical oxidation[19][20][21].

- Aqueous fluoride ions are the primary end products of PRD, enabling real-time reaction monitoring with a fluoride ion selective electrode (ISE), which is far less expensive and faster than relying on PFAS analytical data alone to monitor system performance.

Disadvantages

- The CTAB additive is only partially consumed during the reaction, and although CTAB is not problematic when discharged to downstream treatment processes that incorporate aerobic digestors, CTAB can be toxic to surface waters and anaerobic digestors. Therefore, disposal options for treated solutions will need to be evaluated on a site-specific basis. Possible options include removal of CTAB from solution for reuse in subsequent PRD treatments, or implementation of an oxidation reaction to degrade CTAB.

- The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS). It is hypothesized that in high TDS solutions (e.g., ion exchange still bottoms with TDS of 200,000 ppm), the presence of ionic species inhibits the association of the electron donor with the micelle, thus decreasing the reaction rate.

- The PRD reaction rate decreases in water matrices with very low UV transmissivity. Low UV transmissivity (i.e., < 1 %) prevents the penetration of UV light into the solution, such that the utilization efficiency of UV light decreases.

State of the Art

Technical Performance

| Analytes | GW | FF | AFFF Rinsate |

AFF (diluted 10X) |

IDW NF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Σ Total PFASa (ND=0) | % Decrease |

93% (370) |

96% (32,000) |

89% (57,000) |

86 % (770,000) |

84% (82) |

| Σ Total PFAS (ND=MDL) | 93% (400) |

86% (32,000) |

90% (59,000) |

71% (770,000) |

88% (110) | |

| Σ Total PFAS (ND=RL) | 94% (460) |

96% (32,000) |

91% (66,000) |

34% (770,000) |

92% (170) | |

| Σ Highly Regulated PFASb (ND=0) | >99% (180) |

>99% (20,000) |

95% (20,000) |

92% (390,000) |

95% (50) | |

| Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=MDL) | >99% (180) |

98% (20,000) |

95% (20,000) |

88% (390,000) |

95% (52) | |

| Σ Highly Regulated PFAS (ND=RL) | >99% (190) |

93% (20,000) |

95% (20,000) |

79% (390,000) |

95% (55) | |

| Σ High Priority PFASc (ND=0) | 91% (180) |

98% (20,000) |

85% (20,000) |

82% (400,000) |

94% (53) | |

| Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=MDL) | 91% (190) |

94% (20,000) |

85% (20,000) |

79% (400,000) |

86% (58) | |

| Σ High Priority PFAS (ND=RL) | 92% (200) |

87% (20,000) |

86% (21,000) |

70% (400,000) |

87% (65) | |

| Fluorine mass balanced | 106% | 109% | 110% | 65% | 98% | |

| Sorbed organic fluorinee | 4% | 4% | 33% | N/A | 31% | |

| Notes: GW = groundwater GW FF = groundwater foam fractionate AFFF rinsate = rinsate collected from fire system decontamination AFFF (diluted 10x) = 3M Lightwater AFFF diluted 10x IDW NF = investigation derived waste nanofiltrate ND = non-detect MDL = Method Detection Limit RL = Reporting Limit aTotal PFAS = 40 analytes + unidentified PFCA precursors bHighly regulated PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA cHigh priority PFAS = PFNA, PFOA, PFHxA, PFBA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, HFPO-DA dRatio of the final to the initial organic fluorine plus inorganic fluoride concentrations ePercent of organic fluorine that sorbed to the reactor walls during treatment | ||||||

The PRD reaction has been validated at the bench scale for the destruction of PFAS in a variety of environmental samples from Department of Defense sites (Table 1). Enspired SolutionsTM has designed and manufactured a fully automatic commercial-scale piece of equipment called PFASigatorTM, specializing in PRD PFAS destruction (Figure 2). This equipment is modular and scalable, has a small footprint, and can be used alone or in series with existing water treatment trains. The PFASigatorTM employs commercially available UV reactors and monitoring meters that have been used in the water industry for decades. The system has been tested on PRD efficiency operational parameters, and key metrics were proven to be consistent with benchtop studies.

Bench scale PRD tests were performed for the following samples collected from Department of Defense sites: groundwater (GW), groundwater foam fractionate (FF), firefighting truck rinsate ( AFFF Rinsate), 3M Lightwater AFFF, investigation derived waste nanofiltrate (IDW NF), ion exchange still bottom (IX SB), and Ansulite AFFF. The PRD treatment was more effective in low conductivity/TDS solutions. Generally, PRD reaction rates decrease for solutions with a TDS > 10,000 ppm, with an upper limit of 30,000 ppm. Ansulite AFFF and IX SB samples showed low destruction efficiencies during initial screening tests, which was primarily attributed to their high TDS concentrations. Benchtop testing data are shown in Table 1 for the remaining five sample matrices.

During treatment, PFOS and PFOA concentrations decreased 96% to >99% and 77% to 97%, respectively. For the PFAS with proposed drinking water Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) recently established by the USEPA (PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFBS, and HFPO-DA), concentrations decreased >99% for GW, 93% for FF, 95% for AFFF Rinsate and IDW NF, and 79% for AFFF (diluted 10x) during the treatment time allotted. Meanwhile, the total PFAS concentrations, including all 40 known PFAS analytes and unidentified perfluorocarboxylic acid (PFCA) precursors, decreased from 34% to 96% following treatment. All of these concentration reduction values were calculated by using reporting limits (RL) as the concentrations for non-detects.

Excellent fluorine/fluoride mass balance was achieved. There was nearly a 1:1 conversion of organic fluorine to free inorganic fluoride ion during treatment of GW, FF and AFFF Rinsate. The 3M Lightwater AFFF (diluted 10x) achieved only 65% fluorine mass balance, but this was likely due to high adsorption of PFAS to the reactor.

Application

Due to the first-order kinetics of PRD, destruction of PFAS is most energy efficient when paired with a pre-concentration technology, such as foam fractionation (FF), nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, or resin/carbon adsorption, that remove PFAS from water. Application of the PFASigatorTM is therefore proposed as a part of a PFAS treatment train that includes a pre-concentration step.

The first pilot study with the PFASigatorTM was conducted in late 2023 at an industrial facility in Michigan with PFAS-impacted groundwater. The goal of the pilot study was to treat the groundwater to below the limits for regulatory discharge permits. For the pilot demonstration, the PFASigatorTM was paired with an FF unit, which pre-concentrated the PFAS into a foamate that was pumped into the PFASigatorTM for batch PFAS destruction. Residual PFAS remaining after the destruction batch was treated by looping back the PFASigatorTM effluent to the FF system influent. During the one-month field pilot duration, site-specific discharge limits were met, and steady state operation between the FF unit and PFASigatorTM was achieved such that the PFASigatorTM destroyed the required concentrated PFAS mass and no off-site disposal of PFAS contaminated waste was required.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Boyer, T.H., Fang, Y., Ellis, A., Dietz, R., Choi, Y.J., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Anion Exchange Resin Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Impacted Water: A Critical Review. Water Research, 200, Article 117244. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117244 Open Access Manuscript.pdf

- ^ Strathmann, T.J., Higgins, C.P., Boyer, T., Schaefer, C., Ellis, A., Fang, Y., del Moral, L., Dietz, R., Kassar, C., Graham, C, 2023. Regenerable Resin Sorbent Technologies with Regenerant Solution Recycling for Sustainable Treatment of PFAS; SERDP Project ER18-1063 Final Report. 285 pages. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Dixit, F., Dutta, R., Barbeau, B., Berube, P., Mohseni, M., 2021. PFAS Removal by Ion Exchange Resins: A Review. Chemosphere, 272, Article 129777. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129777

- ^ Rahman, M.F., Peldszus, S., Anderson, W.B., 2014. Behaviour and Fate of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Drinking Water Treatment: A Review. Water Research, 50, pp. 318–340. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.045

- ^ Fuller, Mark. Ex Situ Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Groundwater Using Ion Exchange with Regeneration; ER18-1027. Project Website.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Fang, Y., Ellis, A., Choi, Y.J., Boyer, T.H., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) Using Ion-Exchange and Nonionic Resins. Environmental Science and Technology, 55(8), pp. 5001–5011. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00769

- ^ Interstate Technology Regulatory Council (ITRC), 2023. Technical Resources for Addressing Environmental Releases of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). ITRC PFAS Website

- ^ Gagliano, E., Sgroi, M., Falciglia, P.P., Vagliasindi, F.G.A., Roccaro, P., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Water by Adsorption: Role of PFAS Chain Length, Effect of Organic Matter and Challenges in Adsorbent Regeneration. Water Research, 171, Article 115381. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115381

- ^ Woodard, S., Berry, J., Newman, B., 2017. Ion Exchange Resin for PFAS Removal and Pilot Test Comparison to GAC. Remediation, 27(3), pp. 19–27. doi: 10.1002/rem.21515

- ^ Liu, C. J., Murray, C.C., Marshall, R.E., Strathmann, T.J., Bellona, C., 2022. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from Contaminated Groundwater by Granular Activated Carbon and Anion Exchange Resins: A Pilot-Scale Comparative Assessment. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 8(10), pp. 2245–2253. doi: 10.1039/D2EW00080F

- ^ Liu, C.J., Werner, D., Bellona, C., 2019. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) from Contaminated Groundwater Using Granular Activated Carbon: A Pilot-Scale Study with Breakthrough Modeling. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 5(11), pp. 1844–1853. doi: 10.1039/C9EW00349E

- ^ Ellis, A.C., Boyer, T.H., Fang, Y., Liu, C.J., Strathmann, T.J., 2023. Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Cost Analysis of Anion Exchange and Granular Activated Carbon Systems for Remediation of Groundwater Contaminated by Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Water Research, 243, Article 120324. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.120324

- ^ Ellis, A.C., Liu, C.J., Fang, Y., Boyer, T.H., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2022. Pilot Study Comparison of Regenerable and Emerging Single-Use Anion Exchange Resins for Treatment of Groundwater Contaminated by per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Water Research, 223, Article 119019. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.119019 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Boyer, T.H., Ellis, A., Fang, Y., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of Regeneration Options for Anion Exchange Resin Remediation of PFAS Impacted Water. Water Research, 207, Article 117798. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117798 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ Houtz, E., (projected completion 2025). Treatment of PFAS in Groundwater with Regenerable Anion Exchange Resin as a Bridge to PFAS Destruction, Project ER23-8391. Project Website.

- ^ Strathmann, T.J., Higgins, C., Deeb, R., 2020. Hydrothermal Technologies for On-Site Destruction of Site Investigation Wastes Impacted by PFAS, Final Report - Phase I. SERDP Project ER18-1501. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ Huang, Q., Woodard, S., Nickleson, M., Chiang, D., Liang, S., Mora, R., 2021. Electrochemical Oxidation of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Still Bottoms from Regeneration of Ion Exchange Resins Phase I - Final Report. SERDP Project ER18-1320. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChenEtAl2020 - ^ Veciana, M., Bräunig, J., Farhat, A., Pype, M. L., Freguia, S., Carvalho, G., Keller, J., Ledezma, P., 2022. Electrochemical Oxidation Processes for PFAS Removal from Contaminated Water and Wastewater: Fundamentals, Gaps and Opportunities towards Practical Implementation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 434, Article 128886. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886

- ^ Trojanowicz, M., Bojanowska-Czajka, A., Bartosiewicz, I., Kulisa, K., 2018. Advanced Oxidation/Reduction Processes Treatment for Aqueous Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) – A Review of Recent Advances. Chemical Engineering Journal, 336, pp. 170–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.153

- ^ Wanninayake, D.M., 2021. Comparison of Currently Available PFAS Remediation Technologies in Water: A Review. Journal of Environmental Management, 283, Article 111977. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111977